Tengu

Share

Tengu (天狗, "heavenly dog") are a type of legendary creature in Japanese folk religion, and they are also considered Shinto gods (kami) or yōkai. Although their name contains the word "dog" like the Chinese demon Tiāngǒu, tengu originally took the form of raptors, and they are traditionally depicted with both human and avian characteristics.

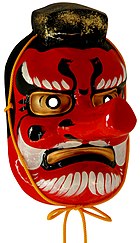

The earliest tengu are depicted with beaks, but this trait has often been humanized into an abnormally long nose, which is currently widely considered the defining characteristic of tengu in the popular imagination.

Buddhism has long considered tengu to be disruptive demons and harbingers of war. Their image has gradually softened, however, although they are considered protectors, they are still dangerous kami of the mountains and forests. The tengu are associated with the ascetic practice known as shugendō, and they are usually depicted in the distinctive costume of its disciples, the yamabushi.

Tengu Image

In art, tengu appear in a wide variety of forms, but they usually fall somewhere between a large monstrous bird and a fully anthropomorphic being, often with a red face or an abnormally large or wide nose.

The earliest depictions of tengu show them as kite-like creatures that can take on human form, often with wings, a bird's head or a beak. The long noses of tengu seem to have been conceived in the 14th century, as a humanization of the original bird beak.

The long noses of the tengu link them with the Shinto deity Saruta-hiko, who is described in the Japanese historical text, the Nihon Shoki, with a similar protuberance measuring seven palms in length. At village festivals, both figures are often portrayed by the same red mask with a phallic nose.

Some of the earliest depictions of tengu appear in Japanese illustrated scrolls, such as the Tenguzōshi Emaki (天狗草子絵巻), painted around 1296, which parodies high-ranking priests by endowing them with the hawk-like beaks of tengu demons.

The tengu are often depicted as taking the form of priests. In the early thirteenth century, tengu began to be associated particularly with yamabushi, the mountain ascetics who practiced shugendō.

The association made its way into Japanese art, where tengu are most frequently depicted in the distinctive costume of yamabushi, which includes a small black hat (頭襟, tokin) and a 結袈裟 (yuigesa). Due to their aesthetic as priests, they are often shown carrying the Khakkhara, a staff used by Buddhist monks.

Tengu are usually depicted holding a magical ha-uchiwa (羽団扇, "feather fan"). In folk tales, these fans sometimes have the ability to make a person's nose grow or shrink, but usually they are attributed with the power to cause strong winds. Various other strange accessories can be associated with tengu, such as high and jagged geta, called tengu-geta.

Tengu Origin

The term tengu and the characters used to write it come from a kind of ferocious demon in Chinese folklore called tiāngǒu. Chinese literature assigns a variety of descriptions to this creature, but most often it is a fierce, anthropophagous canine monster that resembles a shooting star or comet.

It makes a thunderous noise and brings war wherever it falls. A text by Shù Yì Jì (述異記, A Collection of Bizarre Stories), written in 1791, describes a dog similar to the tiāngoǔ with a sharp beak and an upright posture, but usually the tiāngoǔ has little resemblance to its Japanese counterparts. The tiāngoǔ is the most common dog in Japan.

Chapter 23 of the Nihon Shoki, written in 720, is generally considered the first written mention of the tengu in Japan. In this writing, a large shooting star appears and is identified by a Buddhist priest as a "celestial dog," and like the tiāngoǔ of China, the star precedes a military uprising.

However, Chinese characters for tengu are used in the text, accompanied by the phonetic characters, furigana, which give a reading as amatsukitsune ("heavenly fox"). W. de Visser speculated that the ancient Japanese tengu may represent an amalgam of two Chinese spirits: the tiāngoǔ and the fox-spirit named huli jing.

Because the transformation of the tengu from a dog-meteor to a bird-man was unclear, some Japanese scholars have held the theory that the image of the tengu derives from the Hindu eagle deity, Garuda, which has been presented, on numerous occasions in Buddhist writings, as part of one of the major races of non-human beings.

Like the tengu, the garuda is often portrayed as a human life form with wings and a bird's beak. The name tengu seems to have been written in place of garuda in the Japanese sutras called Emmyō Jizō-kyō (延命地蔵経), but this was written in the Edo period, long after the image of the tengu had become established.

At least one ancient story in the Konjaku monogatari shū describes a tengu carrying off a dragon, reminiscent of the garuda's feud with the nāga snakes. However, the original behavior of the tengu differs remarkably from that of the garuda, who are generally friendly toward Buddhism.

De Visser surmised that the tengu might be descended from an ancient bird demon that was merged into both garuda and tiāngoǔ when Buddhism arrived in Japan. However, he found little evidence to support this view.

In the latest version of the Kujiki, an ancient Japanese historical text, it is written the name of Amanozako, a monstrous female deity born from the ferocity spat out by the god Susanoo, with the characters meaning "tengu deity" (天狗神).

The book describes Amanozako as a raging creature capable of flight, with the body of a human, the head of a beast, a long nose, long ears, and long teeth that can grind swords. An eighteenth-century book called Tengu Meigikō (天狗名義考?) suggests that this goddess may be the true predecessor of the tengu, but the dates and authenticity of the Kujiki, and of this edition in particular, are questionable.

Tengu as Evil spirit and angry ghost

The Konjaku monogatari shū, a collection of stories published in the late Heian period, contains some of the earliest tengu stories, already characterized as they would be for centuries to come.

These tengu are troublesome opponents of Buddhism; they deceive pious people with false images of Buddha, kidnapping monks and depositing them in remote places, possessing women in an attempt to seduce holy men, stealing from temples and providing those who worship them with unholy power.

They often disguise themselves as priests or nuns, but their true form seems to be that of a kite.

Throughout the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, stories continue to be told of tengu trying to cause trouble in the world. They are then seen as ghosts of angry, heretical, or senselessly dead priests who had fallen into the tengu (天狗道, tengudō) realm.

They began to possess people, especially women and girls, and spoke through their mouths (kitsunetsuki). Still enemies of Buddhism, the demons then turned their attention to the royal family. The Kojidan gives an account of an empress who was possessed, and the Ōkagami monogatari reports that the emperor Sanjō was blinded by a tengu, the ghost of a priest who wanted to take revenge on him.

One of the renowned tengu of the tenth century was himself the ghost of an emperor. The Hōgen monogatari tells the story of Emperor Sutoku, who was forced by his father to abandon the throne.

He embarked on the Hōgen rebellion to retake the country from Emperor Go-Shirakawa, but was defeated and exiled to Sanuki province in Shikoku. According to legend, he died in great torment vowing to haunt Japan like a great demon and then became a frightening tengu with long claws and kite-like eyes.

In stories from the thirteenth century, the tengu began by kidnapping young boys as well as priests, who were their favorite prey. The boys were often returned, while the priests were discovered tied to the top of a tree or other high place. All tengu victims, however, returned in a state close to death or madness, sometimes after having been driven to eat animal excrement.

The tengu of this period are often conceived as ghosts of arrogant people who become creatures strongly associated with vanity and pride. Today, the Japanese expression tengu ni naru, literally, "to become a tengu," is still used to describe a conceited person.

Tengu as Big and small demons

In the Genpei Jōsuiki, written at the end of the Kamakura period, a god appears to Go-Shirakawa and gives a detailed account of the tengu ghosts. He says that they became tengu because, as Buddhists, they cannot go to hell, and given their evil deeds while alive, they cannot attain nirvana.

He describes the appearance of different types of tengu: the ghosts of priests, nuns, ordinary men and women, all those who were too proud in their past life. The god introduces the notion that not all tengu are equal; learned men become daitengu (大天狗?, "great tengu"), but the ignorant become kotengu (小天狗?, "little tengu").

The philosopher Hayashi Razan listed the greatest of these daitengu as Sōjōbō of Kurama, Tarōbō of Atago, and Jirōbō of Hira Mountains. The demons of Kurama and Atago are among the most renowned tengu.

A section of the Tengu Meigikō, later annotated by Inoue Enryō, lists the daitengu in this order:

- Sōjōbō (僧正坊?) from Mount Kurama

- Tarōbō (太郎坊?) from Mount Atago

- Jirōbō (二郎坊?) from Mount Hira

- Sanjakubō (三尺坊?) of Mount Akiha

- Ryūhōbō (笠鋒坊?) of Mount Kōmyō

- Buzenbō (豊前坊?) from Mount Hiko

- Hōkibō (伯耆坊?) of Daisen

- Myōgibō (妙義坊?) of Mount Ueno (Ueno Park)

- Sankibō (三鬼坊?) of Itsukushima

- Zenkibō (前鬼坊?) of Mt. Ōmine

- Kōtenbō (高天坊?) by Katsuragi

- Tsukuba-hōin (筑波法印?) of Hitachi province

- Daranibō (陀羅尼坊?) of Mount Fuji

- Naigubu (内供奉?) of Mount Takao

- Sagamibō (相模坊?) from Shiramine

- Saburō (三郎?) from Mount Iizuna

- Ajari (阿闍梨?) from Higo province

Daitengu are often depicted in a more human form than their subordinates, and because of their long noses, they are also called hanatakatengu (鼻高天狗?, "long-nosed tengu"). The kotengu are more like birds. They are sometimes called karasu-tengu (烏天狗?, "raven tengu"), or koppa- or konoha-tengu (木葉天狗, 木の葉天狗?).

Inoue Enryō describes two kinds of tengu in his Tenguron: the large daitengu and the small, bird-like konoha-tengu living in cedars. Konoha-tengu are mentioned in a 1746 book called the Shokoku Rijin Dan (諸国里人談?). They are described as bird-like creatures with wingspans of two meters, which have been seen catching fish in the Ōi-gawa River, but this name rarely appears in the rest of the literature.

Creatures that are not classical birds or yamabushi are sometimes called tengu. For example, tengu as woodland spirits may be called guhin (occasionally written kuhin) (狗賓?), but this word may also refer to tengu with a dog's mouth or other characteristics.

Residents of Kōchi Prefecture in Shikoku believe in a creature called shibaten or shibatengu (シバテン, 芝天狗?), but it is a small, childlike being that enjoys sumo wrestling, lives in water most of the time, and is generally considered to be a kind of kappa.

Another tengu residing in water is the kawatengu (川天狗?, "tengu" of the rivers) of Greater Tokyo. This creature was rarely seen, but was believed to create strange fireballs and thus was a nuisance to fishermen.

Tengu as Protective deities and spirits

The Shasekishū, a book of Buddhist parables from the Kamakura period, distinguishes between good and bad tengu. The book explains that the former are in charge of the latter and are the protectors, not the opponents, of Buddhism-although pride or ambition caused them to fail on the demon path, they remain basically good, dharma[unclear]-respecting people as they were in life.

The unpleasant image of the tengu continues to erode in the seventeenth century. Some stories depict them as much less malevolent, protecting and blessing Buddhist institutions rather than threatening or burning them.

According to an eighteenth-century legend Kaidan Toshiotoko (怪談登志男?), a tengu assumed the form of a yamabushi and piously served the abbot of a Zen monastery, until the man guessed his servant's true form. The wings and the huge nose of the tengu then appeared. The tengu asked his master for a piece of wisdom and left while continuing, unseen, to provide miraculous help to the monastery.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, humans began to fear the tengu, who were vigilant protectors of certain forests. In 1764, in a collection of strange stories, the Sanshu Kidan (三州奇談?), a story is told of a man walking through a deep valley and collecting leaves.

It was then that he faced a sudden and fierce hailstorm. A group of peasants later told him that he had gone to the valley where the guhin lived, and that anyone who took a single leaf from that place would surely die.

In the Sōzan Chomon Kishū (想山著聞奇集?), written in 1849, the author describes the customs of the woodcutters of Mino province, who used a rice cake called kuhin mochi to appease the tengu, who would otherwise perpetrate all sorts of mischief. In other provinces, a kind of fish, called okoze, was given to the tengu by the woodcutters and hunters in exchange for a successful day's work.

The people of Ishikawa Prefecture believed until recently that tengu hated mackerel. So they used these fish as a charm against abductions and to prevent the tengu from haunting them.

Tengu are revered as benevolent kami in various Japanese religious cults. For example, the tengu Saburō of Mount Iizuna is worshipped on this and many other mountains as Izuna Gongen (飯綱権現, īzuna gongen, "incarnation of Izuna"), one of the primary deities of the Izuna Shugen cult, which is also related to kitsune sorcery and the dakini of Tantric Buddhism.

Izuna Gongen is represented as a winged figure with a beak and snakes wrapped around his legs, surrounded by a halo of flames, riding a fox and wielding a sword. Tengu worshippers of other sacred mountains adopted similar images for their deity, such as Sanjakubō (三尺坊) or Akiba Gongen (秋葉権現) of the Akiba and Dōryō Gongen (道了権現) of the Saijō-ji Temple in Odawara.

Tengu In folk tales

Tengu appear frequently in orally transmitted tales collected by Japanese folklorists. As these stories are often humorous, they tend to portray tengu as grotesque creatures who are easily tricked or ridiculed by humans. Some of these folktales include:

The 天狗の隠れみの (Tengu no Kakuremino?). A boy looks through a piece of bamboo and claims that he can see places in the distance. A tengu, made curious, offers to exchange the bamboo for a magical straw cloak that makes its wearer invisible.

Having fooled the tengu, the boy continues his misdeeds using the cloak. Another version of the story tells of an ugly old man who tricks a tengu into giving him his magic cloak. The old man causes chaos in his village because of the cloak. The story ends with the tengu regaining the cloak through a game of riddles and punishing the man by turning him into a wolf.

The 瘤取り爺さん (Kobu-tori Jiisan). An old man has a lump (or tumor) on his face. In the mountain, he meets a group of tengu who are partying and he joins their dance. The demons like him so much that they want to see him again the next night and offer him a present.

They take the bump off his face, thinking that he would want to take it back, so he would come back. A mean neighbor, who also has a hump, hears about the old man's good fortune and tries to do the same thing but steals the gift. The tengu, however, simply gives him his neighbor's hump while leaving him his own, disgusted by his poor dancing skills and dishonesty.

The 天狗の羽団扇 (Tengu no Hauchiwa). A rascal obtains the magic fan of a tengu, which can enlarge or shrink noses. He secretly uses the item to enlarge the nose of a rich merchant's daughter, then has it shortened in exchange for her hand. Later, accidentally, he fans himself while sleeping, and his nose becomes so long that it reaches heaven, causing him painful problems.

The 天狗の瓢箪 (Tengu no Hyōtan). A bettor meets a tengu, who asks him what he is most afraid of. The bettor lies and claims that he is terrified of gold or mochi. The tengu answers sincerely that he is afraid of this kind of plant or that ordinary object.

The monster, thinking he is playing a cruel trick, rains money or mochi on the bettor. The bettor is of course delighted and decides to scare the tengu with what he is most afraid of. The bettor then gets the tengu's magic gourd (or other treasure) that he left behind.

The Tengu and the woodcutter. A tengu annoys a woodcutter, showing him his supernatural ability to guess everything a man is thinking. The woodcutter swings his axe and a splinter of wood hits the tengu's nose. The tengu runs away, terrified, exclaiming that humans are dangerous and unpredictable creatures.

Tengu in Martial arts

During the fourteenth century, tengu began to prey on others outside of the Buddhist clergy, and like their menacing ancestors-the tiāngoǔ-tengu became creatures associated with war. Legends lend them great knowledge in the art of combat.

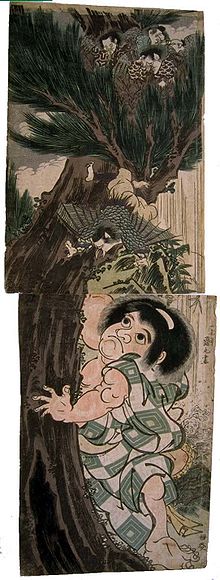

This reputation seems to have its origin in a legend surrounding the famous warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune. When Yoshitsune was a young boy named Ushiwaka-maru, his father, Yoshitomo, was murdered by the Taira clan.

Taira no Kiyomori, the head of the Taira, allowed the boy to survive if he went into exile in the temple on Mount Kurama and became a monk. But one day, in the Sōjō-ga-dani valley, Ushiwaka met the tengu of the mountain, Sōjōbō. This spirit taught the boy the art of fencing so that he could take revenge on the Taira.

Originally, the actions of this tengu were described as another attempt by demons to cause chaos and war, but when Yoshitsune's fame as a legendary warrior grew, his monstrous master was eventually portrayed in a more respectable and sympathetic light.

In one of the most famous renditions of the story, the noh play Kurama Tengu, Ushiwaka is the only person in the temple who did not flee at the sight of this strange yamabushi. Sōjōbō then befriends the boy and becomes his master, out of compassion for all his past hardships.

Two nineteenth-century stories continue this theme: in the Sōzan Chomon Kishū, a boy was kidnapped by a tengu and spent three years with the creature. He returned home with a magic gun that never missed its target.

A story from Inaba province, told by Inoue Enryō, tells of a girl with little skill with her hands who is suddenly possessed by a tengu, who wishes to revive the art of fencing in the world. One day, a young samurai appears and the tengu appears to him in a dream. Thereafter, the possessed girl will teach him fencing in the manner of a master.

Tengu in Modern fiction

Deeply rooted in the Japanese imagination for centuries, tengu continue to be popular subjects in modern fiction in Japan and are growing in popularity in other countries. They often appear as main characters and creatures in Japanese movies, anime, manga, and video games.

- The tengu appears in several video games as a protagonist or monster to fight, including Guild Wars Factions, Dead or Alive 2, MadWorld, Touhou Project, Okami, Muramasa: The Demon Blade, Sekiro and Dungeon Crawl. Sometimes only the name is kept to designate enemies, like soldiers in Metal Gear Solid 2, a roboto in Mega Man 8 or a strategic cruiser in the MMORPG Eve Online. The Tengalice in Pokémon is inspired by the tengu.

- The tengu is a recurring character in Japanese manga and anime:

- Iô Kuroda wrote a manga with a tengu theme, The Tengu Clan.

- Haruka (Tactics) (en), from the Japanese anime and manga Tactics (manga) (en). Haruka takes the form of a tall young man with raven wings and an unusually large nose for a manga [unclear].In Gantz, during the Osaka mission (volumes 22 and 23), one of the three leaders of the monsters is a tengu.

- In the manga Shaman King, a tengu appears under the name Dai Tengu and is a spirit of the class of gods who serves the Asakura family, invoked first by Yôhken Asakura then by Tamamura Tamao.

- The father of Ryo Sakazaki and Yuri Sakazaki, namely Takuma Sakazaki in the Art of Fighting saga, and later in SNK's The King of Fighters saga has a secret identity known as Mr. Karate which he hides under a Tengu mask.

- In the Tastunoko anime Karas, the main character is a raven-like protective spirit.

- Kyo in the manga Black Bird is a tengu like the rest of his clan.

- In the manga Toriko, the cook Tengu Buranchi is, as his name indicates, a tengu.

- In the manga and anime Kakuriyo no Yadomeshi (Kakuriyo: Bed and Breakfast for Spirits) tengu are present, especially Matsuba and his third son Hatori, two tengu from Mount Shumon in the Hidden Kingdom called Kakuriyo.

- In the manga and the anime Kimetsu no Yaiba (Demon Slayer), the character Sakonji Urokodaki is represented wearing a tengu mask.

- In the saga Yo-Kai Watch, there is a spirit with a long red nose named Tengu. This Yo-Kai masters the wind, recalling the tengu of Japanese folklore.

- Two tengus appear in the manga Sweet Years, by Jiro Taniguchi, after Hiromi Kawakami.

- In Urusei Yatsura (Lamu) by Rumiko Takahashi, Princess Kurama is a young tengu from outer space. She is the daughter of Yoshitsune (a legendary character trained by tengu) and is named after the mountain where he retired according to Japanese folklore.

- In the manga Divine Nanami (in anime Kamisama hajimemashita), Kurama Shinjiro is a tengu of Mount Kurama.

- In Pathfinder, the tengu is a race presented in the Bestiary.

- In the 2009 movie RoboGeisha, high-ranking geisha soldiers are called Tengun and wear long-nosed red masks modeled after the human form of tengu. Tengu Milk is one of their attacks.