Japanese Art

Share

The art of Japan (日本美術 Nippon bijutsu) is an expression of Japanese culture, developed over time in various periods and styles that have been happening chronologically, in parallel to the historical, social and cultural evolution of the Japanese people.

The evolution of Japanese art has been marked by the development of its technology, being one of its distinctive signs the use of indigenous materials. As in Western art, the main artistic manifestations have had their origins in religion and political power.

One of the main characteristics of Japanese art is its eclecticism, stemming from the diverse peoples and cultures that have arrived on its shores over time: the first settlers in Japan - known as the Ainu - belonged to a Caucasian branch from northern and eastern Asia, possibly arriving when Japan was still united to the continent.

The origin of these settlers is uncertain, with historians considering various hypotheses, from an Ural-Altaic race to a possible Indonesian or Mongolian origin. In any case, their culture seemed to correspond to the Upper Paleolithic or Mesolithic.

Subsequently, several groups of Malay race from Southeast Asia or the Pacific Islands arrived on the Japanese coasts - at the same time as in Korea and various parts of China - and were gradually introduced from the south, displacing the Ainu to the north of Japan, while in a later wave several groups of the same ethnicity arrived in Japan from China and Korea.

To this racial mix must be added the influence of other cultures: due to its insularity, Japan has been isolated for much of its history, but at intervals it has been influenced by continental civilizations, especially from China and Korea, especially since the 5th century.

Thus, to the ancestral Japanese culture derived from successive waves of immigration was added the foreign influence, forging an eclectic art open to innovation and stylistic progress.

It is also worth noting that much of the art produced in Japan has been of a religious nature: to the Shinto religion, the most typically Japanese, formed around the 1st century, Buddhism was added around the 5th century, forging a religious syncretism that still endures today, and which has also been reflected in art.

Japanese art is thus a reflection of these different cultures and traditions, interpreting in its own way the artistic styles imported from other countries, which they assume according to their concept of life and art, reinterpreting and simplifying their peculiar characteristics, such as the elaborate Chinese Buddhist temples, which in Japan underwent a process of reduction of their superfluous and decorative elements.

This shows the syncretic character of Japanese art, which has always accepted naturally any innovation from other countries.

In Japanese culture, art has a great sense of introspection and interrelation between man and nature, also represented in the objects that surround him, from the most ornate and emphatic to the most simple and everyday.

This is evident in the value given to imperfection, to the ephemeral nature of things, to the emotional sense that the Japanese establishes with his environment.

Thus, for example, in the tea ceremony, the Japanese value the calm and tranquility of that state of contemplation that they achieve with a simple ritual, based on simple elements and a harmony coming from an asymmetrical and unfinished space.

For the Japanese, peace and harmony are associated with warmth and comfort, qualities that are in turn a true reflection of their concept of beauty.

Even when it comes to eating, it is not the quantity of food or its presentation that matters, but the sensory perception of the food and the aesthetic sense they give to any act. Similarly, Japanese artists and artisans have a high degree of attachment to their work, feeling the materials as an essential part of their life and their communication with the environment around them.

Fundamentals of Japanese art

Japanese art, like the rest of its philosophy - or, simply, its way of looking at life - is prone to intuition, lack of rationality, emotional expression and simplicity of acts and thoughts, often expressed symbolically.

Two of its distinctive characteristics are simplicity and naturalness: artistic manifestations are a reflection of nature, so they do not require an elaborate production, but are based on an economy of means that gives art a great transcendence, as a reflection of something higher that is only sketched, suggested, being subsequently interpreted by the viewer.

This simplicity provoked in painting a tendency towards linear drawing, without perspective, with an abundance of empty spaces, which are nevertheless harmoniously integrated into the whole. In architecture, it is reflected in linear designs, with asymmetrical planes, in a conjunction of dynamic and static elements.

In turn, this simplicity is related to an innate naturalness in the relationship between art and nature, which for the Japanese is a reflection of their inner life, and they feel it with a delicate sense of melancholy, almost sadness. In particular, the passing of the seasons gives them a sense of transience, seeing in the evolution of nature the ephemerality of life.

This naturalness is reflected especially in the architecture, which blends harmoniously into its surroundings, as is evident in the use of natural materials, unworked, showing its rough, rough, unfinished appearance. In Japan, nature, life and art are inextricably linked, and artistic achievement is a symbol of the totality of the universe.

In Japan, art aims to achieve universal harmony, going beyond matter to find the life-giving principle. Japanese aesthetics seeks to find the meaning of life through art: beauty equals harmony, creativity; it is a poetic impulse, a sensory path that leads to the realization of the work, which has no purpose in itself, but goes beyond.

Beauty is an ontological category, which refers to existence: it consists in reaching meaning with the whole. As Suzuki Daisetsu said: "beauty is not in the external form, but in the meaning it expresses". Art is not based on sensitive qualities, but on suggestive ones; it does not have to be perfect, but to express a quality that leads to totality.

It is intended to capture the essential through the part, which suggests the whole: emptiness is a complement to that which exists. In Eastern philosophy there is a unity between matter and spirit, predominating contemplation and communion with nature, by way of inner adhesion, of intuition.

In Japan, art (gei) has a more transcendent sense, more immaterial than the concept of art applied in the West: it is any manifestation of the spirit -understood as vital energy, as essence that breathes life into our body-, making it develop and evolve, achieving a unity between body, mind and spirit.

The sense of art has been developing in Japanese aesthetics over time: the first reflections on art and beauty come from antiquity, when the creative principles of Japanese culture were forged and the main epic works of Japanese literature emerged:

- the Kojiki (Tales of Ancient Things),

- the Nihonshoki (Annals of Japan)

- and the Man'yōshū (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves).

A good example of this is the Shinto temple of Ise, built in cypress wood, which has been rebuilt every twenty years since the eighth century to preserve its purity and freshness. From this concept stems one of the constants of Japanese art: the value placed on ephemeral, transitory, fleeting beauty, which evolves over time.

In Man'yōshū sayakeshi is reflected in the feelings of fidelity and honesty, as well as in the depiction of natural elements such as the sky and the sea, which inspire a sense of grandeur that overwhelms man. Sayakeshi is linked to the concept of naru ("becoming"), where time is valued as a vital energy that converges in the becoming, in the consummation of all acts and all lives.

Later, during the Nara and Heian periods, Japanese aesthetics evolved rapidly thanks to its contact with Chinese culture, as well as the arrival of Buddhism. The main concept of this period was aware, an emotional feeling that overwhelms the viewer and leads to a deep sense of empathy or pity.

It is linked to other terms such as okashi, that which attracts by its joy and pleasant character; omoshiroshi, property of radiant things, which attract attention by their brightness and clarity; yūbi, concept of grace, elegance; yūga, quality of refinement in beauty; en, the attraction of charm; rei, the beauty proper to calmness; yasashi, the beauty of discretion; and ushin, the deep sense of the artistic.

A milestone in Japanese culture at this time was Murasaki Shikibu's Tale of Genji, which embodied a new aesthetic concept called mono-no-aware -a term introduced by Motōri Norinaga-, which conveys a feeling of melancholy, of contemplative sadness derived from the transience of things, of ephemeral beauty, which lasts an instant and lingers in the memory.

It is a state of recreation derived from the transience of things and a bittersweet sadness in its wake, equivalent to some extent to the Greek pathos and the Virgilian term lacrimae rerum ("tears of things"). In the words of Kikayama Keita: "it is the deep feeling that overwhelms us when we contemplate a beautiful spring morning, and also the sadness that overwhelms us when we look at an autumn sunset.

This idea of an ideal search for beauty, of a state of contemplation where thought and the world of the senses come together, is characteristic of the innate Japanese sensitivity to beauty, and is evident in the Hanami festival, based on the contemplation of the cherry blossoms.

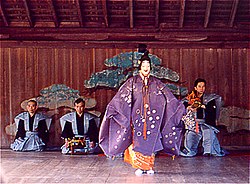

During the Japanese Middle Ages (Kamakura, Muromachi and Momoyama periods), parallel to the militarism of Japanese feudal society, the concept of dō ("way") took hold, emphasizing the creative process of art, the ceremonial practice of social rites, as evidenced in shodō (calligraphy), chadō (tea ceremony), kadō or ikebana (the art of flower arranging) and kōdō (incense ceremony).

In these practices it is not the result that matters, but the evolutionary process, the becoming in time-again the naru-as well as the talent demonstrated in the perfect execution of the rites, which denotes dexterity, as well as a spiritual striving for perfection.

These new concepts were decisively influenced by a variant of Buddhism called Zen, which emphasized certain "rules of life" based on meditation, where the person loses self-consciousness. Thus, any daily work transcends its material essence to signify a spiritual manifestation, which is reflected in the movement and ritual passage of time.

This concept is also reflected in gardening, which reaches such a degree of transcendence that the garden is a vision of the cosmos, with a great emptiness (sea) that is filled with objects (islands), embodied in sand and rocks, and where vegetation is evocative of the passage of time.

The Zen ambivalence between simplicity and the depth of a transcendent life imbued a spirit of "simple elegance" (wabi) not only in art, but also in behavior, social relations and the most everyday aspects of life. Master Sesshū said that "Zen and art are one. "

Zen is based on seven aesthetic principles: fukinsei (asymmetry), way of denying perfection to achieve the balance present in nature; kanso (austerity), eliminating the unnecessary and superfluous to discover the simplicity of nature; kokō (solitary dignity), quality that people and objects acquire with the passage of time and gives them a greater purity of their essence;

shizen (naturalness), which is linked to sincerity, the natural is authentic and incorruptible; yūgen (depth), the true essence of things, which transcends their mere materiality, their superficial aspect; datsuzoku (detachment), freedom in the practice of the arts, whose mission is to liberate the spirit, not to control it-thus, art dispenses with all kinds of norms and rules; seiyaku (inner serenity), a state of stillness, of calm, necessary for the flow of the six previous principles.

Particularly significant is the tea ceremony, where the Japanese concept of art and beauty is masterfully synthesized, creating an authentic aesthetic religion: "theism". This ceremony represents the worship of the beautiful in opposition to the vulgarity of everyday existence.

His philosophy, both ethical and aesthetic, expresses the integral conception of man with nature. Its simplicity relates small things to the cosmic order: life is an expression, and acts always reflect a thought. The temporal is equal to the spiritual, the small to the great.

This concept is also reflected in the tea room (sukiya), an ephemeral construction due to a poetic impulse, stripped of ornamentation, where the imperfect is worshiped, and always leaves something unfinished, which will complete the imagination.

The absence of symmetry is characteristic, due to the Zen conception that the search for perfection is more important than perfection itself. Beauty can only be discovered by the one who mentally completes the incomplete.

Finally, in the modern period, beginning with the Edo period, although the previous concepts remain, some new aesthetic categories were introduced, related to the new urban classes that emerged as Japan modernized:

sui is a certain spiritual finesse, found mainly in the literature of Osaka; iki is an honest and direct elegance, present especially in kabuki theater; karumi is a concept that extols lightness as an essential quality under which the "depth" of things is reached, reflected especially in haiku poetry;

shiori is a nostalgic beauty; hosomi is a delicacy that reaches the essence of things; and sabi is simple beauty, stripped down, without adornment or artifice, extolling values such as poverty and solitude.

The latter was linked to the previous concept of wabi, creating a new notion called wabi-sabi, the transcendence of simplicity, where beauty resides in imperfection, in incompleteness, based on transience and impermanence. Underlying all these concepts again is the idea of art as a creative process, and not as a material realization.

Okakura Kakuzō wrote that "only artists persuaded of the imperfection congenital to their soul are capable of engendering true beauty. "

Japanese Art Periodization

For study, the art of Japan is divided into major periods in terms of artistic production and important political developments. The classification often varies depending on the author's criteria, and many of them can be subdivided. On the other hand, there are also divergences as to the beginning and end of some of these periods.

Japanese Art Plastic

Jōmon Period (11000 B.C.-500 B.C.)

During the Mesolithic and Neolithic Japan remained isolated from the mainland, so all its production was indigenous, though of little significance. They were semi-sedentary societies, living in small villages with houses dug into the ground, obtaining their food resources mainly from the forest (deer, wild boar, nuts) and the sea (fish, crustaceans, marine mammals).

These societies had an elaborate organization of work, and were concerned with the measurement of time, as evidenced by various remains of circular stone arrangements at Oyu and Komakino, which acted as sundials. They apparently had standardized units of measurement, as attested by various buildings constructed according to certain patterns.

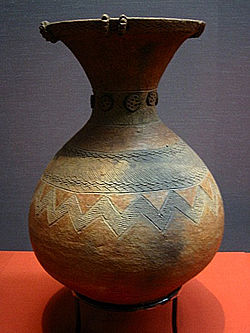

Bone tools and polished stones, pottery and anthropomorphic figures have been found at the various Jōmon sites. It should be noted that Jōmon pottery is the oldest pottery produced by humans: the earliest remains of rudimentary pottery date back to 11,000 BC, in small hand-worked vessels, with polished sides and wide interiors, with a functional sense and austere decoration.

These vestiges correspond to a period called "prejōmon" (11000-7500 BC), which was succeeded by the "archaic" or "early Jōmon" (7500-2500 BC), where the most typical Jōmon pottery is made, handmade and decorated with incisions or rope impressions, on a base of a type of deep jar-shaped vessels.

The basic decoration consisted of impressions made with strings made from plant fibers, which were pressed onto the pottery before firing. In several areas these incisions reached a high degree of elaboration, with perfectly chiseled edges, drawing a series of abstract cut signs of great complexity.

On a few occasions, traces of figurative scenes have been found, generally anthropomorphic and zoomorphic drawings (frogs, snakes), highlighting a hunting scene present in a vase found in Nirakubo, north of Honshū.

Finally, in the "late Jōmon" (2500-400 BC), the vessels return to more natural forms, less elaborate, with bowls and vessels with rounded bottoms, narrow-necked amphorae and bowls with handles, often with a foot or raised base.

The main sites of Jōmon pottery are: Taishakukyo, Torihama, Togari-ishi, Natsushima, Kamo, and Okinohara on the island of Honshū; Sobata on the island of Kyūshū; and Hamanasuno and Tokoro on the island of Hokkaidō.

Apart from vases, several figurines in human or animal form were built in ceramics, constructed in parts, so few remains of whole pieces have been found. Those of anthropomorphic form can have masculine or feminine attributes, and some have also been found with androgynous signs.

Some have a bulging belly, so they were possibly linked to the cult of fertility. It is worth noting the precision in the details that some figures show, such as elaborate hairstyles, tattoos and decorative clothing. It seems to be that in these societies the corporal adornment had great relevance, mainly in the ears, with ceramic earrings of diverse manufacture, decorated with red pigments.

In Chiamigaito (Honshū Island) more than 1,000 of these ornaments have been found, which suggests a local workshop for the production of these products. Also dating from this period are various masks that indicate individualized work on the faces.

Likewise, various types of green jadeite beads were made, and they knew how to work with lacquer, as evidenced by several hairpins found in Torihama. Remains of swords made of ivory, bone or animal antlers have also been found.

Yayoi Period (500 B.C.-A.D. 300)

This period saw the definitive establishment of the agricultural society, which led to the deforestation of large areas of the territory. This transformation led to an evolution of Japanese society in the technological, cultural and social fields, with greater social stratification and specialization of work, and led to an increase in warfare.

The Japanese archipelago was dotted with small states formed around clans (uji), among which the Yamato clan prevailed, giving rise to the imperial family. Shintoism appeared, a mythological religion that made the emperor descend from Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun.

This religion gave rise to the original sense of purity and freshness of Japanese art, with a predilection for pure, undecorated materials, with a sense of integration with nature (kami or supraconsciousness). From the 1st century B.C., civilization began to be introduced from the continent, due to relations with China and Korea.

The Yayoi culture appeared on the island of Kyūshū around 400-300 B.C., passing to Honshū, where it gradually displaced the Jōmon culture. During this period, a type of large burial chamber and burial mound ornamented with terracotta cylinders with human and animal figures was widespread.

The settlements were enclosed by ditches, and various utensils related to agriculture appeared (especially a crescent-shaped stone tool used for harvesting), as well as various weapons, such as bows and arrows with polished stone tips.

Pottery was produced on a potter's wheel, mainly wide-necked jars, lidded jars, wide plates, cups with handles and narrow-necked bottles. They were of polished surface, with simple decoration, mainly incisions, stippling and zig-zag serpentines. The main modality was a jar-shaped vessel called tsubo.

Metalwork, mainly bronze, stood out, such as bells called dotaku, which served as ceremonial objects, decorated with spirals (ryusui) in the form of flowing water, or animals in relief (mainly deer, birds, insects and amphibians), as well as scenes of hunting, fishing and agricultural work, especially those related to rice.

The deer seems to have had a special significance, perhaps linked to some divinity: in many sites a multitude of deer shoulder blades have been found with incisions or marks made with fire, so it would be linked to some kind of ritual.

Other decorative objects found in Yayoi sites include mirrors, swords, various beads and magatama (pieces of jade and agate in the shape of cashew nuts, which served as fertility jewelry).

Kofun period (300-552)

This era saw the consolidation of the imperial central state, which controlled the main resources, such as iron and gold. The architecture was developed preferably in the funerary field, with characteristic chamber and corridor tombs called kofun ("ancient tomb"), over which earthen burial mounds of large proportions were raised.

Of particular note are the large tombs of the emperors Ōjin (346-395) and Nintoku (395-427), where various jewelry, weapons, stone or terracotta sarcophagi, pottery and anthropomorphic terracotta figures called haniwa, consisting of a cylindrical pedestal and a half bust, were found.

These statuettes were about 60 centimeters, with hardly any expression, only some slits in the eyes and mouth, although they constitute a sample of great relevance of the art of this time. According to their clothing and utensils, various trades can be distinguished in these figures, such as farmers, soldiers, priestesses, courtesans, musicians and dancers.

At the end of this period, animal figurines also appeared, especially deer, dogs, horses, wild boars, cats, chickens, sheep and fish.

A great variety of weapons have been found (teams of archers, crowns with matagama jewelry, bronze stirrups), which indicates the importance of the military establishment at this time, whose stylistic features are related to the Silla culture of Korea, as well as a type of pottery called Sueki, dark and of great fineness, with tinkling accessories.

Social differentiation led to the isolation of the ruling classes in exclusive enclosures within the cities, as in Yoshinogari, to end up definitively segregated in isolated enclosures such as that of Mitsudera or the palace complexes of Kansai, Ikaruga and Asuka-Itabuki.

In terms of religious architecture, the first Shinto temples (jinja) were made of wood, on a raised platform and bare walls or sliding partitions, with pillars supporting the roof, which is sloping. One of its characteristic elements is the torii, an entrance arch that signals access to a sacred place.

It is worth mentioning the Ise shrine, which has been rebuilt every twenty years since the eighth century. It comprises two complexes, the western (Naikū), dedicated to Amaterasu (goddess of the sun), and the eastern (Gekū), dedicated to Toyouke no Ōmikami (goddess of clothing, food, housing, agriculture and industry), with a total of about 125 shrines.

The main building (Shoden) has a raised ground plan and a gabled roof, on nine columns, accessed by an exterior staircase. It is in the shinmeizukuri style, reflecting the late Shintō style, prior to the arrival of Buddhism in Japan. The shrine is a pilgrimage center (o-ise-mairi), since, according to tradition, Shintō practitioners must visit the shrine at least once in their lifetime.

Another mythical temple of uncertain origin is Izumo Taisha, near Matsue, legendarily founded by Amaterasu. It is of taishazukuri style, considered the oldest among the shrines, characterized by the elevation of the building on pilasters, with a staircase as the main entrance, and simple unpainted wooden finishes.

According to the chronicles, the original sanctuary had a height of 50 meters, but due to a fire it was rebuilt with a height of 25 meters. Its main buildings are the Honden ("inner sanctuary") and the Haiden ("outer sanctuary"). The Kinpusen-ji, the main temple of the shugendō, an ascetic religion that combines Shintoism, Buddhism and animistic beliefs, also belongs to this period.

Its structure includes the main temple or Zaōdō, which is the second largest wooden construction in Japan, only surpassed by the Daibutsuden of Tōdai-ji; together with the Niō Gate, it has been listed as a National Treasure of Japan.

In this period we find the first samples of painting, as in the royal burial of Ōtsuka and the dolmen-shaped tombs of Kyūshū (5th-6th centuries), decorated with scenes of hunting, war, horses, birds and boats, or else with spirals and concentric circles.

They were wall paintings, made with hematite red, charcoal black, yellow ochre, kaolin white and chlorite green. One of the representative drawings of this period is the so-called chokkomon, composed of straight lines and arcs drawn on diagonals or crosses, and present on the walls of tombs, sarcophagi, haniwa statues and bronze mirrors.

Asuka period (552-710)

The Yamato state forged a centralized kingdom following the Chinese model, embodied in the laws of Shōtoku-Taishi (604) and the Taika of 646. The arrival of Buddhism produced in Japan a great impact on the artistic and aesthetic level, with strong influence of Chinese art.

Especially fruitful for art was the rule of Prince Shōtoku (573-621), who favored Buddhism and culture in general. The architecture, in the form of temples and monasteries, was mostly lost, entailing the replacement of simple Shinto lines by magnificence from the mainland.

As the most remarkable building of this period, the temple of Hōryū-ji (607), representative of the Kudara style (Paikche in Korea), should be mentioned. It was built on the site of the Wakakusadera temple, erected by Shōtoku and burned by his enemies in 670.

Built with an axial planimetry, it consists of a group of buildings where the pagoda (Tō), the Yumedomo ("hall of dreams") and the Kondō ("golden hall") stand out. It is in the Chinese style, with a ceramic tile roof being used for the first time.

Another characteristic example is Itsukushima Shrine (593), built on the water, on the Seto Inland Sea, with the Gojūnotō ("five-tiered pagoda"), the Tahōtō ("two-tiered pagoda") and several honden (buildings with altars) standing out among its buildings. It was named a World Heritage Site in 1996.

The sculpture, of Buddhist theme, was in wood or bronze: the first images of Buddha were imported from the mainland, but then a large number of Chinese and Korean artists settled in Japan.

The image of Kannon, the Japanese name for the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara (called Guanyin in Chinese), proliferated, such as the Bodhisattva Kannon, work of the Korean Tori; the Kannon located in the Yumedomo of the temple of Hōryū-ji; and the Kannon of Kudara (6th century), made by an unknown artist.

Another work of note is the Sâkyamuni Triad (623), in bronze, by Tori Busshi installed in the temple of Hōryū-ji. In general, they were works of a severe, angular and archaizing style, inspired by the Korean Koguryŏ style, as seen in the work of Shiba Tori, which marked the "official style" of the Asuka period: Great Buddha Asuka (Hoko-ji temple, 606), Yakushi Buddha (607), Kannon Guze (621), Shaka Triad (623).

Another artist who followed this style was Aya no Yamakuchi no Okuchi Atahi, author of the Four Heavenly Guardians (shitenno) of the Golden Hall of Hōryū-ji (645), which despite the archaic air present a volumetric evolution in the more rounded forms, with more expressive faces.

The painting followed Chinese patterns, in ink or mineral pigments on silk or paper, on scrolls or hanging on the wall.

It denotes a great sense of drawing, with works of great originality, such as the Tamamushi (Hōryū-ji) reliquary, in camphor wood and cypress, with bronze filigree bands, presenting several scenes in oil on lacquered wood, in a technique called mitsuda-i from Persia and related to Chinese painting of the Wei dynasty.

At the base of the reliquary is a jataka (account of Buddha's previous lives), showing Prince Mahasattva offering his own flesh to a hungry tigress. At this time, calligraphy began to gain prominence and was given the same level of artistry as figurative images.

Silk tapestries also stood out, such as the Tenjukoku Mandala dedicated to Shōtoku (622). Ceramics, which could be glazed or unglazed, had little local production, with Chinese imports being more highly valued.

Nara Period (710-794)

During this period the capital was established in Nara (710), the first fixed capital of the mikado. Buddhist art had its heyday during this period, while the Chinese influence continued to be strong - the Japanese saw in Chinese art a harmony and perfection similar to the European taste for classical Greco-Roman art.

The few examples of architecture of the period are buildings with a monumental air, such as the East Pagoda of Yakushi-ji, the temples of Tōshōdai-ji, Tōdai-ji and Kōfuku-ji, and the imperial storehouse Shōso-in in Nara, which preserves a multitude of art objects from the time of Emperor Shōmu (724-749), with works from China, Persia and Central Asia.

The city of Nara was built according to a grid plan, following the model of Chang'an, the capital of the Tang dynasty. Equal importance was given to the imperial palace as to the main monastery, the Tōdai-ji (745-752), built according to a symmetrical plan in a large enclosure with twin pagodas, and featuring the Daibutsuden, the "great Buddha hall", with a large bronze statue of the 15-meter Vairocana Buddha (Dainichi in Japanese), donated by Emperor Shōmu in 743.

Rebuilt in 1700, the Daibutsuden is the largest wooden building in the world. Another important enclosure of the temple is the Hokkedō ("lotus hall", also called Sangatsudō, "hall of the third month"), which has another magnificent statue, the Kannon Fukukenjaku, an eight-armed bodhisattva made of lacquer, four meters high and Tang influence, noticeable in the serenity and placidity of the facial features.

On the other hand, the East Pagoda of Yakushi-ji was an attempt by Japanese architects to find their own style, moving away from the Chinese influence. It stands out for its verticality, with alternating roofs of different sizes, giving it the appearance of a calligraphic sign. In its structure the eaves and balconies stand out, formed by interlaced wooden bars, in white and brown colors.

Inside it houses the image of the Yakushi Nyorai ("Medicine Buddha"). It is registered as a World Heritage Site under the designation of Historical Monuments of Ancient Nara.

Equally assimilated nationally was the Tōshōdai-ji (759), which shows a clear contrast between the Kondō ("golden hall"), of a solidity, symmetry and verticality of Chinese influence, and the Kodō ("conference hall"), of a greater simplicity and horizontality that denote the indigenous tradition.

Another exponent was the Kiyomizu-dera (778), whose main building stands out for its enormous railing, supported by hundreds of pillars, which juts out from the hill and offers impressive views of the city of Kyoto.

This temple was one of the candidates for the list of New Seven Wonders of the World, although it was not chosen. Meanwhile, Rinnō-ji is famous for the Sanbutsudō ("Hall of the Three Buddhas"), where three gold-laminated statues of Amida, Senjūkannon (Thousand-Armed Kannon) and Batōkannon (Horse-headed Kannon) are located.

As a Shinto shrine, the Fushimi Inari-taisha (711), dedicated to the spirit of Inari, was particularly noted for the thousands of red toriis that mark the path down the hill on which the shrine is situated.

The representation of the Buddha was highly developed in sculpture, with statues of great beauty: Sho Kannon, Buddha of Tachibana, Bodhisattva Gakko of Tōdai-ji. In the Hakuhō period (645-710), the removal of the Soga clan and the imperial consolidation brought about the end of Korean influence and its replacement by Chinese influence (Tang dynasty), producing a series of works of greater magnificence and realism, with rounder and more graceful forms.

This change is perceptible in the group of gilt bronze statues of Yakushi-ji, composed of the seated Buddha (Yakushi) flanked by the bodhisattvas Nikko ("Sunlight") and Gakko ("Moonlight"), who show greater dynamism in their contrapposto posture, and greater facial expressiveness.

In contrast, at Hōryū-ji the Tori style of Korean origin continued, as in the Kannon Yumegatai and the Amida Triad of Lady Tachibana's Reliquary. In the temple of Tōshōdai-ji is a triad of statues of colossal size, made of hollow dry lacquer, with the central Rushana Buddha (759), 3.4 meters high, standing out.

There are also representations of guardian spirits (Meikira Taisho), kings (Kamokuten), etc. They are works in wood, bronze, raw clay or dry lacquer, of great realism.

Painting is represented by the mural decoration of Hōryū-ji (late 7th century), such as the frescoes of the Kondō, which show similarities with those of Ajantā in India. Various typologies also emerged, such as kakemono ('hanging painting') and emakimono ('scroll painting'), stories painted on a paper or silk scroll, with texts explaining the various scenes, called sutras.

In the Shōso-in of Nara there is a series of paintings of profane subject matter, with various genres and themes: plants, animals, landscapes and metal objects. In the middle of the period, the Tang dynasty style of painting became fashionable, as can be seen in the murals of the Takamatsuzuka tomb, from around 700.

By the Taiho-ryo decree of 701, the painter's trade was regulated in craft guilds controlled by the Department of Painters (edakumi-no-tuskasa), under the Ministry of the Interior. These guilds were in charge of decorating palaces and temples, and their structure lasted until the Meiji era. Ceramics evolved notably thanks to various techniques imported from China, such as the use of bright colors applied to the clay.

Heian period (794-1185)

This period saw the rule of the Fujiwara clan, which established a centralized state inspired by the Chinese government, with its capital in Heian (present-day Kyoto). The great feudal lords (daimyō) emerged, and the figure of the samurai appeared.

At this time the hiragana script emerged, which adapted Chinese calligraphy to the polysyllabic Japanese language, using Chinese characters for the phonetic values of the syllables. The rupture of relations with China produced a more typically Japanese art, emerging alongside religious art a secular art that would be a faithful reflection of the nationalism of the imperial court.

Buddhist iconography had a new development with the importation of two new sects from the continent, Tendai and Shingon, based on Tibetan Tantric Buddhism, which incorporated Shinto elements and produced a religious syncretism characteristic of this era.

Shingon was a type of esoteric Buddhism centered on the relationship between matter and spirit, which was reflected in mandalas, pictorial or sculpted images that focused on the Diamond (spiritual world) and the Mother Breast (material world), as well as representations of the Dainichi Nyorai (the "Great Sun").

For its part, Tendai focused on the salvation of man, with a certain morality of Confucian origin and a great syncretism with the Shinto religion. It gave great importance to art, and it was even said that the Tendai turned "religion into art and art into religion". One of its main cults was the Western Paradise of the Pure Land of Amida, of which numerous images were made.

One of the most flourishing was the image of the raigo-zu, Buddha transporting souls to Paradise, which proliferated in numerous paintings, such as the central panel of the Amida Triptych at Hokkeji (Nara).

Architecture underwent a change in the plan of the monasteries, which were erected in secluded places, intended for meditation. The most important temples are Enryaku-ji (788), Kongōbu-ji (816) and the shrine-pagoda of Murō-ji. Enryaku-ji, located in the surroundings of Mount Hiei, is part of the Historic Monuments of Ancient Kyoto, declared a World Heritage Site in 1994.

It was founded in 788 by Saichō, who introduced the Tendai Buddhist sect to Japan. Enryaku-ji came to have about 3000 temples, and was a huge center of power in its time, most of its buildings being destroyed by Oda Nobunaga in 1571.

Of the part that survived, the Saitō ("west hall") and the Tōdō ("east hall") stand out today, where the Konpon chūdō is located, the most representative construction of Enryaku ji, where a statue of Buddha sculpted by Saichō himself, the Yakushi Nyorai, is preserved.

In civil architecture, the construction of the Imperial Palace, of pure Japanese style, was outstanding. During the Fujiwara period (897-1185), the temple was again located in the city, being the meeting place of the ruling classes. The religious architecture imitated that of the great palaces, with a highly developed decoration, as in the monastery of Byōdō-in -also called of the Phoenix-, in Uji (founded in 1053).

In this temple stands out the Hōōdō ("Hall of the Phoenix"), located at the edge of a pond that gives it a lyrical and spiritual appearance, with dynamic and elegant lines where the roofs with curvilinear corners stand out, giving an ascending air to the whole.

This hall preserves an image of the Amida Buddha ("Lord of Infinite Light"), 2.5 meters tall, in lacquered wood, the work of the master Jōchō.

Sculpture suffered a slight decline compared to earlier periods. Once again, representations of the Buddha stand out (Nyoirin-Kannon; Yakushi Nyorai from the temple of Jingo-ji in Kyoto; Amida Nyorai in the monastery of Byōdō-in), as well as some Shinto goddesses (Kichijoten, goddess of happiness, equivalent of the Indian Lakshmī).

The excessive rigidity of the Buddhist religion limited the spontaneity of the artist, who was circumscribed by rigid artistic canons that curtailed his creative freedom. Between 859 and 877 the Jogan style was produced, characterized by figures of an almost intimidating severity, with a certain introspective and mysterious air, such as the Shaka Nyorai of Murō-ji.

During the Fujiwara period the school founded by Jōchō at Byōdō-in gained preeminence, with a more graceful and slender style than Jogan sculpture, achieving perfect anatomical proportions and a great sense of movement.

The Jōchō workshop introduced the yosegi and warihagi techniques, which consisted of dividing the figure into two blocks that were later joined to carve them, thus avoiding subsequent cracking, one of the main problems of large figures. These techniques also allowed serial assembly, and were developed with great success in the Kei school of the Kamakura period.

Painting at the beginning of this period was poorly developed, with little creative freedom and the absence of the concept of space. The appearance of the yamato-e ("Japanese painting") school marked the independence of Japanese painting from Chinese influence.

It is characterized by its harmony and its diaphanous and luminous conception, with bright and brilliant colors, simple lines and geometric decoration. The main works are found in Buddhist monasteries (Byōdō-in, Kongōbu-ji).

Of particular note are the murals in the Hall of the Phoenix at Byōdō-in, whose landscapes synthesize for the first time the more properly Japanese aesthetic taste, with its sense of melancholy emotionality.

Typical Chinese elements are replaced by others of Japanese taste, such as cherry blossoms instead of the snowy plum trees fashionable in Tang painting, or rice paddies instead of towering Chinese mountain peaks.

Together with other elements such as wisteria, orchids, peonies, bamboo, the moon, fog, the sea, rain, etc., the most typical Japanese landscape imagery was created at this time.

Likewise, the asymmetrical composition, the empty space, the ethereal atmosphere, the undulating movement, the anecdotal details, the application of color more in stains than in brushstrokes, the lyrical and emotive character of the whole will be typical of Japanese painting, both in murals and in engravings and screens.

Despite this, the Chinese influence continued in public and official buildings, since it was linked to the prestige of the civil service. Referred to as kara-e, Chinese painting thrived in the imperial circle, as seen in works such as the Sages' Screen and the Kunming Lake Screen.

Yamato-e painting developed notably in the handwritten scrolls called emaki, which combined pictorial scenes with elegant katakana calligraphy. These scrolls narrated historical or literary passages, such as the Tale of Genji, a late 10th century novel by Murasaki Shikibu.

While the text was the work of reputed calligraphers, the images were generally executed by courtesans of the court, such as Ki no Tsubone and Nagato no Tsubone, representing a display of feminine aesthetics that would have great relevance in Japanese art.

A distinction then arose between female (onna-e) and male (otoko-e) painting, which marked a perceptible distinction between the public world, considered masculine -whose art maintained the Chinese influence- and the private world, of feminine character and more properly Japanese aesthetics.

In onna-e, in addition to the Tale of Genji, the Heike Nogyo (Lotus Sūtra), commissioned by the Taira clan for Itsukushima Shrine, stood out, with a total of 33 scrolls on the salvation of souls proclaimed by Buddhism.

The otoko-e was more narrative and energetic than the onna-e, more action-packed, with more realism and movement, as in the Shigisan Engi scrolls, about the miracles of the monk Myoren; the Ban Danaigon E-kotoba, about a war of rival clans in the ninth century; and the Chōjugiga, animal scenes of caricatured sign and satirical tone, criticizing the aristocracy.

In this period, ceramics did not have a special relevance, highlighting instead works in lacquer -generally boxes for cosmetics- and metal objects, where mirrors stand out.

In lacquer, the maki-e technique emerged, consisting of sprinkling colored powder, gold and silver on wet lacquer, creating drawings of great finesse and subtle tonality. Sometimes it included inlays of mother-of-pearl (raden). Fans, decorated with texts from Buddhist sutras and genre scenes, also gained prominence.

Kamakura Period (1185-1392)

After various disputes between the feudal clans, the Minamoto clan prevailed and established the shogunate, a military type of government. At this time, the Zen sect was introduced in Japan, which was to have a powerful influence on figurative art.

The architecture was simpler, functional, less luxurious and ornate. The Zen influence led to the so-called Kara-yo style: Zen monasteries followed the Chinese axial planimetry, although the main building was not the temple, but the reading room, and the place of honor was not occupied by a statue of Buddha, but by a small throne where the abbot taught his disciples.

Of particular note are the five large temple complex of Sanjūsangen-dō in Kyoto (1266), as well as Kennin-ji (1202) and Tōfuku-ji (1243) in Kyoto, and Kenchō-ji (1253) and Engaku-ji (1282) in Kamakura. The Kōtoku-in (1252) is famous for its bronze statue of Amida Buddha, 13 meters high and weighing 93 tons, being the second largest Buddha in Japan after that of Tōdai-ji.

In 1234, the temple of Chion-in was built, the seat of Jōdo shū ("Pure Land Sect") Buddhism, notable for its colossal main gate (Sanmon), which is the largest structure of its kind in Japan.

One of the last exponents of this period was Hongan-ji (1321), consisting of two main temples: the Nishi Hongan-ji, which includes the Goei-dō ("founder's hall") and Amida-dō ("Buddha hall") halls, along with a tea pavilion and two nō theater stages, one of which boasts the oldest surviving one; and the Higashi Hongan-ji, where the famous Shosei-en garden is located.

Sculpture acquired great realism, with the artist finding greater creative freedom, as denoted in the portraits of nobles and military men, such as that of Uesugi Shigefusa (by an anonymous artist), a 14th-century military man.

Zen works focused on the representation of their masters, in a type of statue called chinzo, such as that of the master Muji Ichien (1312, anonymous author), in polychrome wood, representing the Zen master seated on a throne, in an attitude of relaxed meditation.

Of particular importance for the quality of his works was the Kei school of Nara, heir to the Jōchō school of the Heian period, where the sculptor Unkei, author of the statues of the monks Muchaku and Seshin (Kōfuku-ji of Nara), as well as images of the Kongo Rikishi (guardian spirits), such as the two colossal statues located at the entrance of the temple Tōdai-ji (1199), 8 meters high, stood out.

Unkei's style, influenced by Chinese sculpture of the Song dynasty, was of great realism, capturing at once the most detailed physiognomic study with the emotional expression and inner spirituality of the individual portrayed.

Dark crystals were even embedded in the eyes, to give greater expressiveness. Unkei's work marked the beginning of Japanese portraiture. His work was continued by his son Tankei, author of the Kannon Senju for the Sanjūsangen-dō.

Painting was characterized by greater realism and psychological introspection. Landscape painting (The Nachi Waterfall) and portraiture (Monk Myoe in Contemplation by Enichi-bo Jonin; portrait collection of the Jingo-ji temple in Kyoto by Fujiwara Takanobu; portrait of Emperor Hanazono by Goshin) developed.

He continued the yamato-e style and narrative scroll painting, some up to 9 meters long. These scrolls reflected aspects of daily life, urban or rural scenes, or illustrated historical events, such as the 1159 war in Kyoto between rival branches of the imperial family.

They were presented in successive scenes, following a narrative order, with an elevated panoramic view, like a bird's eye view. Of particular note are the illustrated scrolls of the events of the Heiji era (Heiji monogatari) and the Kegon Engi scrolls by Enichi-bo Jonin.

The painting related to the Zen sect was more directly Chinese in influence, drawn in simple lines of Indian ink following the Zen maxim that "too many colors blind the vision. "

At this time, the production of what would become the most typically Japanese ceramics began, with the figure of Toshiro standing out. Crafts destined for military life grew, especially armor and swords (katana) made of two layers of iron and steel subjected to ignition and immersion, with a characteristic steam-tempered mark called ni-e.

Muromachi Period (1392-1573)

During this period the shōgunate was held by the Ashikaga, whose infighting favored the growing power of the daimyō, who divided the territory. The architecture was more elegant and typically Japanese, highlighting stately mansions, monasteries such as Zuiho-ji, and temples such as Shōkoku-ji (1382), Kinkaku-ji or Golden Pavilion (1397) and Ginkaku-ji or Silver Pavilion (1489), in Kyoto.

Kinkaku-ji was built as a resting villa for the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, as part of his estate called Kitayama. His son transformed the building into a temple of the Rinzai sect. It is a three-story building, with the upper two floors covered with pure gold leaf.

The pavilion functions as a shariden, storing Buddha relics. It also contains several Buddha statues and bodhisattva figures, and a golden fenghuang or "Chinese phoenix" is located on the roof. It also has a magnificent adjacent garden, with a pond called Kyōko-chi ("mirror of water"), with numerous islands and stones representing the history of Buddhist creation.

For its part, the Ginkaku-ji was built by the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa, who sought to emulate the Kinkaku-ji built by his grandfather Yoshimitsu, but unfortunately could not cover the building with silver as he had planned.

Also characteristic of the architecture of this period is the appearance of the tokonoma, a room reserved for the contemplation of a painting or flower arrangement, in keeping with the Zen aesthetic. Similarly, the tatami, a type of carpet made of rice straw, was introduced, which made the interior of the Japanese home more pleasant.

During this period, the art of gardening developed considerably, laying the artistic and aesthetic foundations of the Japanese garden. Two main forms emerged: tsukiyama, around a hill and a lake; and hiraniwa, a flat garden of raked sand, with stones, trees and wells.

The most common vegetation consists of bamboo and various genera of flowers and trees, whether evergreen, such as Japanese black pine, or deciduous, such as Japanese maple, with elements such as ferns and mosses being equally valued.

Another typical element of gardening and interior design is the bonsai. Gardens often include a lake or pond, various types of pavilions (usually for the tea ceremony) and stone lanterns. One of the typical features of the Japanese garden - as in the rest of their art - is the imperfect, unfinished, asymmetrical appearance.

There are different types of gardens: "strolling", which are contemplated walking along a path or around a pond; "chamber", which are enjoyed from a fixed location, usually a machiya-type pavilion or hut; "tea" (rōji), around a path leading to the teahouse, with tiles or stones to mark the way; and "contemplation" (karesansui, "mountain and water landscape"), which is the most typical Zen garden, contemplated from a platform located in Zen monasteries.

A good example is the so-called Waterless Landscape of Ryōan-ji Garden, in Kyoto, a work by the painter and poet Sōami (1480), which represents a sea -made with raked sand- full of islands -which are rocks-, creating an ensemble that combines reality and illusion and invites to stillness and reflection.

Painting also flourished, framed within the Zen aesthetic, which received the Chinese influence of the Yuan and Ming dynasties, reflected mainly in decorativism.

The technique of gouache was introduced, a perfect transcription of Zen doctrine, which seeks to reflect in landscapes what they mean, rather than what they represent.

The figure of the bunjinso emerged, the "intellectual monk" creator of his own works, scholars and followers of Chinese techniques in monochrome ink, in brief and diffuse brushstrokes, who reflected in their works natural elements such as pines, reeds, orchids, bamboos, rocks, trees, birds and human figures immersed in nature, in an attitude of meditation. Some of these monk-artists were: Mokuan Reien, Gyokuen Bompo, Ue Gukei, etc.

In Japan, this technique with Chinese ink was given the name sumi-e. Based on the seven aesthetic principles of Zen, sumi-e ("ink painting") was intended to reflect the most intense inner emotions through simplicity and elegance, in simple, modest lines that transcend their external appearance to signify a state of communion with nature.

For Zen monks, sumi-e was a way (dō) to seek inner peace, spiritual realization. The subtle and diffuse tonal properties of ink allowed the artist to capture the essence of things, in a simple and natural, yet profound and transcendent impression.

It is a spontaneous art of rapid execution, impossible to retouch, a fact that links it to life, where it is impossible to return to the past. Each brushstroke expresses vital energy (ki), since it is an act of creation, where the spirit is put into action, and where the process is more important than the result.

The main sumi-e artists were: Muto Shui, Josetsu, Shūbun, Sesson Shukei and, above all, Sesshū Tōyō, author of portraits and landscapes, the first artist to paint from life. Sesshū was a gaso, a monk-painter, who traveled to China between 1467 and 1469, where he studied art and natural landscape.

His landscapes are composed of linear structures, illuminated by a sudden light that reflects the Zen concept of the transcendental instant. They are landscapes with the presence of anecdotal elements, such as temples in the distance or small human figures, framed in hidden places like cliffs.

A new genre of poem-painting also emerged, the shigajiku, in which a landscape illustrates a poem of naturalistic inspiration. Mention should also be made of the Kanō school, founded by Kanō Masanobu, which applied the gouache technique to traditional subjects, thus illustrating sacred, national and landscape themes.

Gouache was also applied to screens and painted panels on fusuma sliding doors, characteristic of Japanese interior design. In ceramics, the Seto school stood out, the most popular typology being the so-called temmoku. Also notable examples of this period are the lacquer and metal objects.

Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573-1603)

At this time Japan was again unified by Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, who eliminated the daimyō and succeeded each other in power. Their rule coincided with the arrival of Portuguese traders and Jesuit missionaries, who introduced Christianity to the country, although reaching only a minority.

The artistic production of this period moved away from Buddhist aesthetics, emphasizing traditional Japanese values, with a grandiloquent style. The invasion of Korea in 1592 led to the forced transfer of many Korean artists to Japan, who settled in ceramic production centers isolated from the rest.

Also during this period, the first influences from the West were received, reflected in the Nanban style ("southern barbarians", the name given to the Europeans), developed in miniaturist sculpture, with profane themes, decorative objects in porcelain and screens decorated in yamato-e style, with bright colors and gold leaf, in scenes that narrate the arrival of the Europeans to the Japanese coasts.

Western influence introduced oil painting and the use of perspective, although in general they did not have much success in traditional Japanese art.

In architecture, the construction of large castles (shiro) stood out, which were fortified by the introduction of Western firearms in Japan. Good examples are the castles of Himeji, Azuchi, Matsumoto, Nijō and Fushimi-Momoyama.

Himeji Castle, one of the main constructions of the period, combines massive fortifications with the elegance of a vertical structure, in five stories built in wood and plaster, with roofs of soft curvilinear shapes similar to those of traditional Japanese temples.

Rustic tea ceremony villas, composed of small villas or palaces and large gardens, also proliferated, and wooden theaters were built in some cities for kabuki performances.

In painting, the Kanō school received the majority of official commissions, developing the mural painting of the main Japanese castles. Prominent figures are the names of Kanō Eitoku and Kanō Sanraku.

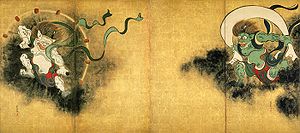

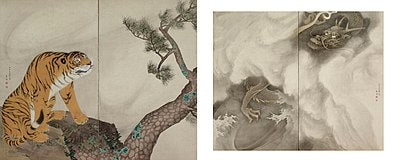

For the castles, with little illumination due to their narrow defensive openings, he created a type of screens with golden backgrounds that reflected the light and spread it throughout the room, with large murals decorated with heroic scenes, animals such as tigers and dragons, or landscapes with the presence of gardens, ponds and bridges, or about the four seasons, a fairly frequent theme at the time.

The yamato-e style continued mainly among the bourgeois class, represented by the Tosa school, which continued the Japanese epic tradition of historical scenes and landscapes, highlighting the figures of Tosa Mitsuyoshi and Tosa Mitsunori.

There was also a notable development of painting on screens, generally in gouache inks, following the sumi-e style, as seen in the work of Hasegawa Tōhaku (Pine Forest) and Kaihō Yūshō (Pine and Plum Tree in Moonlight). The figure of Tawaraya Sōtatsu, author of works of great dynamism, in manuscript scrolls, folding screens and fans, also stood out.

He created a lyrical and decorative style inspired by the waka writing of the Heian period, which was called rinpa, producing works of great visual beauty and emotional intensity, such as The Tale of Genji, The Path of Ivy, The Gods of Thunder and Wind, etc.

Pottery reached a moment of great splendor, with the development of ceramics for the tea ceremony, inspired by Korean pottery, whose rusticity and unfinished appearance perfectly translated the Zen aesthetic that permeates the rite of tea.

New designs emerged, such as nezumi plates and kogan water pitchers, generally with a white body bathed in a layer of feldspar and decorated with simple drawings made with iron slip.

It was a thick, glazed-looking pottery with an unfinished treatment, giving a sense of imperfection and vulnerability. Seto continued to be one of the main centers of production, while in the town of Mino two important schools were born: Shino and Oribe.

The Karatsu school and two original types of pottery also stood out: Iga, with a coarse texture and a thick layer of glaze, with deep cracks; and Bizen, earthenware of a reddish brown and unglazed, removed while still tender from the wheel to produce small cracks and natural incisions that gave it a brittle appearance, again according to the Zen aesthetic of imperfection.

One of the best artists of this period was Honami Kōetsu, who excelled in painting as well as poetry, gardening, lacquerware, etc. Educated in the artistic tradition coming from the Heian period and in the Shorenin school of calligraphy, he founded an artisan colony in Takagamine, near Kyoto, thanks to land given by Tokugawa Ieyasu.

The colony was nurtured by craftsmen of the Nichiren Buddhist school, and produced a number of works of great quality.

They specialized in lacquerware, mainly desk accessories, decorated with inlaid gold and mother-of-pearl, as well as various utensils and tableware for the tea ceremony, highlighting the fujisan bowl, with a reddish body covered with a black slip and, at the top, an opaque white glaze that gives the effect of falling snow.

Edo period (1603-1868)

This artistic period corresponds to the historical Tokugawa period, in which Japan was closed to all outside contact. The capital was established in Edo, the future Tokyo. Christians were persecuted and European merchants expelled.

Despite the system of vassalage, trade and craftsmanship proliferated, and a bourgeois class appeared that grew in power and influence, and dedicated itself to the promotion of the arts, especially engravings, ceramics, lacquerware and textiles.

The most important buildings are the Katsura Palace in Kyoto and the mausoleum of Tōshō-gū in Nikkō (1636), which is part of the "Shrines and Temples of Nikkō," a World Heritage Site recognized by UNESCO in 1999.

Of hybrid Shinto-Buddhist forms, it is the mausoleum of the shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu. The temple is a rigidly symmetrical structure with colored reliefs covering the entire visible surface. It is notable for its colorful buildings and overloaded ornaments that distance themselves from the styles of temples of that era.

The interiors are adorned with lacquerwork, detailed colorful sculptures and masterly painted panels. The Katsura Palace (1615-1662) was built with a Zen-inspired asymmetrical plan, where the straight lines of the exterior facade contrast with the sinuousness of the surrounding garden.

Villa of rest of the imperial family, it includes a main building (Shoin), several pavilions, tea houses and a park of seven hectares. The main palace, which has a single floor, is divided into four pavilions connected at the corners: Shōkintei, Shōkatei, Shōiken and Gepparō.

All are raised on pillars and constructed of wood with whitewashed walls and sliding doors leading to the garden, and contain paintings by Kanō Tan'yū.

Also characteristic of this period are teahouses (chashitsu), usually small wooden buildings with bálago roofs, surrounded by gardens in a state of apparent abandonment, with lichen, moss and fallen leaves, following the Zen concept of transcendent imperfection.

Painting developed notably, acquiring great vitality. It worked in different formats, from wall panels and screens to scrolls, fans and small albums. Wood engraving became very popular, with the emergence of an important industry in urban centers specializing in illustrated texts and prints.

Initially they were engraved in black ink on hand-colored paper, but in the mid-18th century color printing (nishiki-e) emerged.

He continued the rinpa style initiated by Sōtatsu in the work of Ōgata Kōrin, one of the greatest artists of the time. His production, cheerful and sardonic, was aimed at the merchant classes, with works of an urban elegance and a somewhat irreverent realism, although with great virtuosity and a profound knowledge of the classical masters, as he demonstrates in the screens Red and White Plums, Waves, Irises and The Story of Ise.

The Kanō school received the main official government commissions, with a Zen aesthetic style of strong brushstrokes.

Its main representative was Kanō Tan'yū, grandson of Kanō Eitoku, who worked in the imperial palace and Nagoya Castle, while at the same time carrying out a remarkable scholarly work collecting notes on all kinds of works of art, with commentaries and sketches (shukuzu) of the works, a great source of information for art historiography.

The Tosa school was represented by Tosa Mitsuoki, who continued the epic yamato-e tradition.

In the eighteenth century appeared the nanga school or "idealistic painting", of Confucian sign sponsored by the Tokugawa shogunate, highly influenced by Chinese art, which they considered the cradle of their civilization.

It adopted the wenren style of Chinese amateur scholar-painters, reduced to small intellectual circles made up of professionals from diverse backgrounds, from samurai to monks, merchants and officials. Its main point of reference was the school of Li Guo of the Song dynasty, with a broad and curvilinear brushstroke, which reached Japan through the Korean school of An Kyon.

The nerve center of the nanga was the Mampuku-ji monastery, founded in 1661 on the outskirts of Kyoto, which became the center of Chinese culture in Japan. The main subject depicted was landscape, often with elements such as flowers and birds, and the combination of painting and poetry (haiga) was common.

This school produced several artists of great quality: Ikeno Taiga, Yosa Buson, Uragami Gyokudō, Aoki Mokubei, Tani Bunchō, Gibon Sengai, Hakuin Ekaku, etc.

Another interesting pictorial school was born in Kyoto, founded by Maruyama Ōkyo, who combined various techniques and influences, from Chinese to Western, which he learned through Dutch engravings.

He made scrolls and screens with landscapes and gilded backgrounds, a characteristic of his style being the rendering of the landscape with sketches taken directly from nature.

His disciples were Matsumura Goshun, co-founder with Ōkyo of the Maruyama-Shijō school; Itō Jakuchū, an artist of great personality who devoted himself to the genre of still life, rare until then in Japan; and Nagasawa Rosetsu, who mastered the Western techniques of perspective and chiaroscuro.

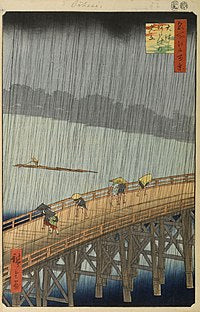

The best known and most notable school was that of ukiyo-e ("prints of the flowing world"), which was noted for its depiction of popular types and scenes.

Developed around the technique of engraving -mainly woodcut-, it was a secular and plebeian style, eminently urban, which, inspired by anecdotal themes and genre scenes, gave them an extraordinary lyricism and beauty, with a subtle sensibility and a refined taste of great modernity.

The founder was Hishikawa Moronobu, who was followed by such figures as Okumura Masanobu, Suzuki Harunobu, Isoda Koryūsai, and Torii Kiyonobu, founder of the Torii school. Several artists specialized in reproducing the actors of Japanese popular kabuki theater (yakusha-e, "actors' tableaux"), with a certain caricatured air, among them Torii Kiyomasu, Torii Kiyomitsu and, above all, Tōshūsai Sharaku.

Another fairly common genre was the bijin-ga ("paintings of beautiful women"), which depicted geishas and courtesans in intimate attitudes and boudoir scenes, with great detail, mainly in their clothing, as denoted in the work of Torii Kiyonaga, Kitagawa Utamaro and Keisai Eisen.

Another variant was the shunga ("spring prints"), with a more explicitly erotic content. Landscape painting was introduced by Utagawa Toyoharu, founder of the Utagawa school, who applied Western perspective to the Japanese landscape.

At the beginning of the 19th century, when ukiyo-e art seemed to decline, the great figure of Katsushika Hokusai appeared, author of some 30,000 drawings that he compiled in 15 volumes, which he entitled Manga (1814). He especially reflected the urban life of Edo, with a certain humorous touch, in an energetic style of strong strokes.

He was also a great representative of landscape painting, one of his main motifs being Mount Fuji, in scenes of great color, with a strongly personal stamp, neither realistic nor idealized, always reflecting the artist's inner vision. One of its last exponents and great master of the school was Utagawa Hiroshige, also a great landscape painter, as denoted in his One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

He had a more realistic style than Hokusai, but more lyrical and evocative, often using a perspective of backgrounds framed in the foreground of branches, leaves or other objects.

Ceramics had one of its major centers of production in Kyoto, influenced by Chinese and Korean art; its leading artist was Nonomura Ninsei. A Korean-influenced school emerged in Hagi, characterized by the use of simple forms and light tonalities, with the figure of Ōgata Kenzan, brother of Ōgata Kōrin, standing out.

Ceramics intended for the tea ceremony continued, decorated with apparently irregular and asymmetrical elements, such as signs and lines of almost abstract cut, according to the ideal of imperfection of Zen aesthetics.

The first porcelains were produced in this period, with a first production center in Arita, in the prefecture of Saga (called Imari porcelain), where the Korean potter Yi Sam-pyeong found in 1616 a type of white clay ideal for porcelain.

Of note were the Kakiemon, Nabeshima and Ko-Kutami schools, which produced a series of plates, bowls and sake bottles of great quality and refinement, with enamel glazes decorated in blue, green, yellow, red, beige and pale eggplant.

Lacquer, metal, ivory and mother-of-pearl objects also proliferated, and objects such as inro (medicine boxes), netsuke (sculpted charms) and tsuba (sword guards) reached great artistic quality.

Similarly, textile art, mainly in silk, became very important and reached very high quality levels, so that often silk tunics (kimono) with bright colors and refined drawings were hung to separate rooms, as if they were screens.

Various techniques were used, such as dyeing, embroidery, brocade, embossing, appliqué and hand-painting. Silk was only available to the upper classes, while the people wore cotton, made according to the Indonesian ikat technique, spun in sections and dyed in indigo alternating with white.

Another technique of lesser quality was the interweaving of cotton threads of different colors, with homemade dyes applied in the batik way by means of a paste of rice and boiled and caked rice bran.

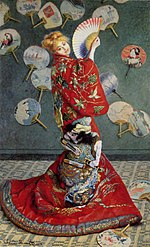

It is worth noting that, just as in the 19th century Japanese art was influenced by Western art, the latter was also influenced by the exoticism and naturalness of Japanese art. Thus arose in the West the so-called Japonisme, developed mainly in the second half of the 19th century, especially in France and Great Britain.

It was manifested in the so-called japonaiseries, objects inspired by Japanese prints, porcelain, lacquerware, fans and bamboo objects, which became fashionable both in interior decoration and in numerous personal garments that reflected the fantasy and decorativism of Japanese aesthetics.

In painting, the style of the ukiyo-e school was enthusiastically received, and the works of Utamaro, Hiroshige and Hokusai were highly appreciated. Western artists imitated the simplified spatial construction, simple contours, calligraphic style and naturalistic sensibility of Japanese painting.

Some of the major artists who received this influence were: Édouard Manet, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, James Tissot, Mary Cassatt, Pierre Bonnard, Georges Ferdinand Bigot, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Paul Gauguin, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Vincent van Gogh, Gustav Klimt, etc.

Contemporary period (from 1868)

The Meiji period (1868-1912) saw the beginning of a profound cultural, social and technological renewal in Japan, which became more open to the outside world and began to incorporate the new advances achieved in the West.

The Charter of 1868 abolished feudal privileges and class distinctions, which did not lead to an improvement of the proletarian classes, who were plunged into misery. An era of strong imperialist expansionism began, which led to the Second World War.

After the war, Japan underwent a process of democratization and economic development that made it one of the world's major economic powers and a leading center of industrial production and technological innovation. The Meiji era was followed by the Taishō (1912-1926), Shōwa (1926-1989) and Heisei (1989-) eras.

From 1930, the progressive militarization and expansion throughout China and South Asia, with the consequent increase in resources allocated to the military budget, led to a decline in artistic patronage.

However, with the post-war economic boom and the new prosperity achieved with the industrialization of the country, the arts were reborn, now fully immersed in the international artistic movements due to the process of cultural globalization.

Likewise, economic prosperity favored collecting, with the creation of numerous museums and exhibition centers that have helped the dissemination and conservation of Japanese and international art.

In the religious sphere, the establishment during the Meiji era of Shintoism as the only official religion (Shinbutsu bunri) led to the abandonment and destruction of Buddhist temples and works of art,

which would have been irreparable without the intervention of Ernest Fenollosa, professor of philosophy at the Imperial University of Tokyo, who together with the magnate and patron William Bigelow rescued a large number of works that nourished the Buddhist art collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D. C.,

which was then moved to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D. C., where it became a museum of Buddhist art. C., two of the world's finest collections of Asian art.

Architecture presents a dual direction: traditional (Yasukuni Shrine, Heian Jingu and Meiji temples in Tokyo) and European-influenced, incorporating new technologies (Yamato Bunkakan Museum by Isohachi Yoshida in Nara).

Westernization led to the construction of new buildings such as banks, factories, train stations and public buildings, built with Western materials and techniques, emulating at first (late 19th century) English Victorian architecture. Some foreign architects also worked in Japan, such as Frank Lloyd Wright (Imperial Hotel, Tokyo).

Architecture and urban planning received a great boost after World War II, due to the need to rebuild the country. A new generation of architects emerged, led by Kenzō Tange, author of works such as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, St. Mary's Cathedral in Tokyo, the Olympic Stadium for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, etc.

Tange and his disciples developed the concept of architecture understood as "metabolism", considering buildings as organic forms that must adapt to functional needs. A movement founded in 1959, they had an idea of the city of the future inhabited by a massified society, characterized by flexible and extensible structures with organic-like growth.

Among its members were Kishō Kurokawa, Akira Shibuya, Youji Watanabe and Kiyonori Kikutake. Another exponent was Maekawa Kunio who, together with Tange, introduced ancient Japanese aesthetic ideas into the rigid contemporary buildings, using again traditional techniques and materials such as tatami and the use of pillars -a traditional construction element in Japanese temples-, or the integration of gardens and sculptures in their designs.

Another Japanese aesthetic principle, that of emptiness, was studied by Fumihiko Maki in the spatial relationship between the building and its surroundings.

Since the 1980s, postmodern art has had a strong presence in Japan, as the fusion between the popular element and the sophistication of forms has been characteristic of Japan since ancient times.

This style has been represented primarily by Arata Isozaki, author of the Kitakyūshū Museum of Art and the Kyoto Concert Hall. Isozaki studied with Tange, and in his work synthesized Western concepts with spatial, functional and decorative ideas typical of Japan.

For his part, Tadao Andō developed a minimalist style, with great concern for the contribution of light and spaces open to the outdoors (Chapel on the Water, Tomanu, Hokkaidō; Church of Light, Ibaraki, Osaka; Children's Museum, Himeji).

Shigeru Ban has been noted for his use of unconventional materials, such as paper or plastic: after the 1995 Kōbe earthquake, which left many people homeless, Ban contributed by designing The Paper House and The Paper Church. Finally, Toyō Itō has explored the physical image of the city of the digital age (Tower of the Winds, Yokohama; Sendai Mediatheque, Sendai; Mikimoto Ginza 2 Building, Tokyo).

In sculpture there was also a duality between tradition and avant-garde, with the names of Yoshi Kinuchi and Romorini Toyofuku standing out, as well as the abstractionists Masakazu Horiuchi and Yasuo Mizui, the latter settled in France. Isamu Noguchi and Nagare Masayuki collected the rich sculptural tradition of their country in works that study the contrast between the roughness and polish of the material.

Painting also followed two currents: traditional (nihonga) and westernist (yōga), although independent of both, the figure of Tomioka Tessai stood out at the beginning of the 20th century.

The nihonga style was promoted at the end of the 19th century by the art critic Okakura Kakuzō and by the educator Ernest Fenollosa, seeking in traditional art the archetypal form of expression of the Japanese sensibility, although this style also received some Western influence, especially from pre-Raphaelitism and romanticism.

It was represented mainly by Hishida Shunsō, Yokoyama Taikan, Shimomura Kanzan, Maeda Seison and Kobayashi Kokei.

The Europeanist style of painting was initially nourished by the techniques and themes in force in Europe at the end of the 19th century, mainly linked to academicism -as in the case of Kuroda Seiki, who studied nine years in Paris-, but later followed the different currents that were being produced in Western art:

The Hakubakai group picked up the impressionist influence; abstract painting had Takeo Yamaguchi and Masanari Munai as leading figures; among figurative artists Fukuda Heichachirō, Tokuoka Shinsen and Higashiyama Kaii stood out. Some artists settled outside their country, such as Genichiro Inokuma in the United States and Tsuguharu Foujita in France.

In the Taishō period, the yōga style predominated over the nihonga, although the increased use of Western light and perspective diminished the differences between the two currents.

Just as nihonga largely adopted the innovations of post-impressionism, yōga manifested a penchant for eclecticism, with a great diversity of divergent artistic movements emerging. During this era, the Japan Academy of Fine Arts (Nihon Bijutsuin) was established.

The painting of the Shōwa era was marked by the work of Yasurio Sotaro and Umehara Ryuzaburo, who introduced the concepts of pure art and abstract painting to the nihonga tradition. In 1931, the Independent Art Association (Dokuritsu Bijutsu Kyokai) was established to promote avant-garde art.

During World War II, censorship and government controls allowed only the expression of patriotic themes. After the war, Japanese artists prospered in the big cities -particularly in Tokyo-, creating an urban and cosmopolitan art, which was following with devotion the stylistic innovations produced internationally, especially in Paris and New York.

After the abstract styles of the 1960s, the 1970s saw a return to the realism favored by pop art, as can be seen in the work of Shinohara Ushio. Even so, in the late 1970s there was a return to traditional Japanese art, in which they saw greater expressiveness and emotional strength.

The tradition of printmaking continued into the 20th century in a style of "creative prints" (sosaku hanga) drawn and carved by artists preferably in the nihonga style, such as Kawase Hasui, Yoshida Hiroshi and Munakata Shiko.

Among the latest trends, the Gutai group, which assimilated the experience of World War II through actions full of irony, with a great feeling of tension and latent aggressiveness, was quite renowned within the so-called action art. Its members include: Jirō Yoshihara, Sadamasa Motonaga, Shozo Shimamoto and Katsuō Shiraga.

Linked to postmodern art are several artists immersed in the recent phenomenon of globalization, marked by the multiculturalism of artistic expressions:

Shigeo Toya, Yasumasa Morimura. Other prominent artists of contemporary Japan are: Tarō Okamoto, Chuta Kimura, Leiko Ikemura, Michiko Noda, Yasumasa Morimura, Yayoi Kusama, Yoshitaka Amano, Shigeo Fukuda, Shigeko Kubota, Yoshitomo Nara and Takashi Murakami.

Japanese Art Other artistic expressions

Literature

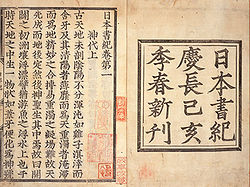

Japanese literature has a strong Chinese influence, mainly due to the adoption of Chinese writing. The oldest preserved testimony is the Kojiki (Tales of Ancient Things), a kind of universal history of mythical and theogonical cut. Another testimony of relevance is the Nihonshoki (Annals of Japan).