Japanese Samurai

Enomoto Takeaki

Enomoto Takeaki (榎本 武揚 , Edo, August 25, 1836 - Tokyo, August 26, 1908) was a Japanese naval admiral loyal to the Tokugawa Shogunate, who fought against the new Meiji...

Enomoto Takeaki

Enomoto Takeaki (榎本 武揚 , Edo, August 25, 1836 - Tokyo, August 26, 1908) was a Japanese naval admiral loyal to the Tokugawa Shogunate, who fought against the new Meiji...

Akiyama Nobutomo

Akiyama Nobutomo (jap. 秋山 信友; b. 1531; December 23, 1575) was a Japanese samurai of the Sengoku period. He is known as one of the 24 generals. Nobutomo was a...

Akiyama Nobutomo

Akiyama Nobutomo (jap. 秋山 信友; b. 1531; December 23, 1575) was a Japanese samurai of the Sengoku period. He is known as one of the 24 generals. Nobutomo was a...

Date Shigezane

Date Shigezane (伊達 成実; 1568 - July 17, 1646) was a Japanese samurai of the late Sengoku and early Edo period, belonging to the Date clan.Shigezane was a son of...

Date Shigezane

Date Shigezane (伊達 成実; 1568 - July 17, 1646) was a Japanese samurai of the late Sengoku and early Edo period, belonging to the Date clan.Shigezane was a son of...

Hōjō Masako

Hōjō Masako (北条 政子; 1157 - August 16, 1225) was a Japanese politician. The eldest daughter of Hōjō Tokimasa (the first shikken, or regent, of the Kamakura shogunate) and his...

Hōjō Masako

Hōjō Masako (北条 政子; 1157 - August 16, 1225) was a Japanese politician. The eldest daughter of Hōjō Tokimasa (the first shikken, or regent, of the Kamakura shogunate) and his...

Fukushima Masanori

Masanori Fukushima (福島正則, Fukushima Masanori, 1561-26 August 1624) was a daimyo in the service of Hideyoshi Toyotomi in Japan during the late Sengoku and early Azuchi Momoyama eras.He fought in...

Fukushima Masanori

Masanori Fukushima (福島正則, Fukushima Masanori, 1561-26 August 1624) was a daimyo in the service of Hideyoshi Toyotomi in Japan during the late Sengoku and early Azuchi Momoyama eras.He fought in...

Hōjō Ujiyasu

Hōjō Ujiyasu (北条 氏康; 1515 - October 21, 1571) was the son of Hōjō Ujitsuna and daimyō of the Hōjō clan. His wife was Suikeiin, sister of Imagawa Yoshimoto. Hōjō...

Hōjō Ujiyasu

Hōjō Ujiyasu (北条 氏康; 1515 - October 21, 1571) was the son of Hōjō Ujitsuna and daimyō of the Hōjō clan. His wife was Suikeiin, sister of Imagawa Yoshimoto. Hōjō...

Epic Gear for Modern Samurais✨

-

Samurai Katana Umbrella

Regular price 62$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Black Steel Oni Necklace

Regular price 38$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Shogun Rage Necklace

Regular price 26$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Japanese Demon Controller Holder Stand

Regular price 35$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Sekiro Mini Katana Sword

Regular price 28$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Black Oni Samurai Menpo Mask

Regular price 234$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

White Oni Samurai Menpo Mask

Regular price 234$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Red Oni Samurai Menpo Mask

Regular price 234$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

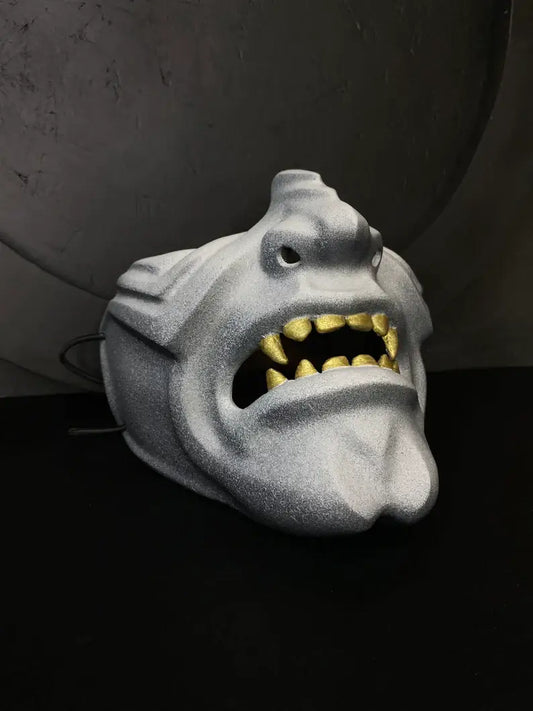

Silver Oni Demon Samurai Mask

Regular price 184$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

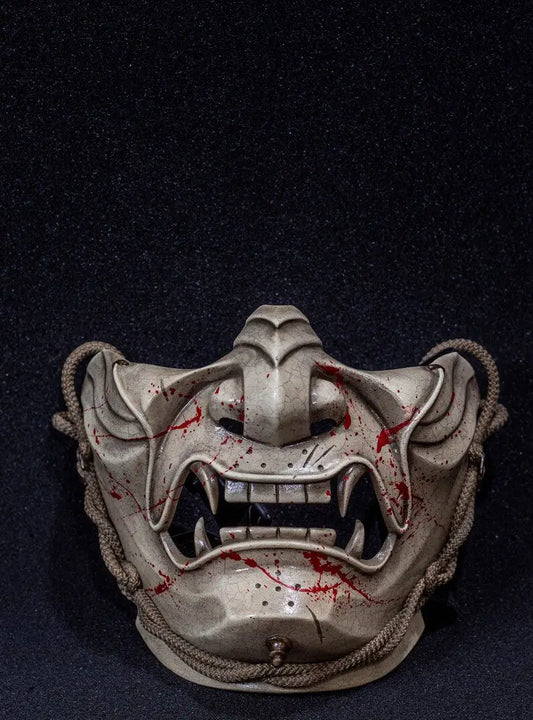

Blood Ghost of Tsushima Samurai Oni Mask

Regular price 214$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Samurai Octopus Katana Enamel Pin

Regular price 17$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Oni Demon Katana Enamel Pin

Regular price 13$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Japanese Samurai Stickers

Regular price 17$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Samurai Horse Rider Shorts

Regular price 33$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Oni Katana Harem Pants

Regular price 38$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Katana Blades Harem Pants

Regular price 38$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Red Samurai Skull Haori

Regular price 35$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Katana Kitsune Haori

Regular price 35$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Red Samurai Haori

Regular price 35$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Samurai White Sakura Haori

Regular price 35$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Black Katana Gear Shifter

Regular price 35$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Samurai Katana Pen

Regular price 17$ USDRegular priceUnit price / per

The Legacy of the Samurai: Warriors of Honor and Tradition

"The way of the warrior is resolute acceptance of death." – Miyamoto Musashi, legendary samurai and author of The Book of Five Rings.

In the heart of feudal Japan, a class of warriors emerged whose dedication to duty and honor would transcend their military prowess. These were the samurai—men and women bound by an unyielding code, whose influence has shaped Japanese history, culture, and even modern ethics. For centuries, the samurai served as protectors, leaders, and exemplars of the virtues embodied in bushido, the "way of the warrior." Their legacy, etched in both blood and ink, continues to inspire awe and respect far beyond the borders of Japan.

The samurai were not merely soldiers; they were symbols of loyalty, discipline, and sacrifice. Serving feudal lords known as daimyos, samurais were skilled in the art of combat and governed by a strict ethical code that demanded personal integrity, loyalty to one's master, and a willingness to face death with calm resolve. They represented the pinnacle of warrior culture, but also contributed deeply to Japan's political structure, arts, and philosophy.

Origins and Historical Background

Early Beginnings

The story of the samurai begins in the 8th and 9th centuries, during Japan's Heian period. Initially, the term "samurai" referred to those who served as armed guards for the aristocracy, tasked with protecting the lands and interests of the imperial court. As regional clans gained power and the central authority of the emperor weakened, these warriors began to evolve into a distinct class. They honed their skills in archery and swordsmanship, gradually transforming from mere protectors into powerful military elites with significant influence over Japan’s political landscape.

In these early days, samurai were as much rural managers and estate overseers as they were fighters. Yet as conflicts between rival clans intensified, particularly over control of land and resources, the need for specialized warriors became paramount. This era laid the foundation for the rise of a warrior class that would dominate Japanese society for centuries to come.

Development of Feudal Japan

By the late Heian period (794–1185), the samurai had become central figures in Japanese politics and warfare. The collapse of the imperial court’s power led to a period of internal strife, marking the beginning of the feudal era. During this time, powerful regional families, or daimyo, rose to prominence. These lords commanded armies of samurai, who were now professional warriors dedicated to defending their territories and expanding their influence.

The Kamakura period (1185–1333) was a turning point in samurai history. After a prolonged struggle between the Taira and Minamoto clans, Minamoto no Yoritomo emerged victorious and established the first shogunate in 1192, marking the start of samurai rule. The shogun, a military dictator, held true power, while the emperor became a symbolic figure. Under the Kamakura shogunate, the samurai class formalized its role as the ruling military aristocracy.

The samurai’s influence continued to grow throughout the Muromachi and Sengoku periods, especially during the chaotic Sengoku (Warring States) era (1467–1615), when rival daimyo fought for control of Japan. It was during these centuries of warfare that the samurai's code of conduct, bushido, began to crystallize, emphasizing loyalty, honor, and martial skill.

Famous Samurai Clans

Several prominent clans shaped the history of Japan and the samurai class. The Minamoto and Taira clans were key players during the late Heian period, culminating in the famous Genpei War (1180–1185), which saw the rise of the first shogunate under Minamoto no Yoritomo. This established the samurai as the ruling class of Japan.

In the Sengoku era, figures like Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu left indelible marks on the country. Oda Nobunaga began the process of unifying Japan after centuries of civil war, ruthlessly defeating rival warlords with innovative military tactics and new technologies like firearms. Toyotomi Hideyoshi continued this process, and Tokugawa Ieyasu completed it, founding the Tokugawa shogunate in 1603. The Tokugawa era brought peace to Japan, and samurai shifted from their traditional role as warriors to bureaucrats and administrators, though they remained the pillars of Japanese society.

Through their military achievements, political strategies, and cultural influence, the samurai forged a legacy that would survive the fall of feudalism and continue to resonate in Japan and beyond.

Bushido: The Way of the Warrior

Philosophy of Bushido

At the heart of the samurai ethos lies bushido, a complex moral code that guided the actions and behaviors of these elite warriors. Translating to "the way of the warrior," bushido was not a rigid doctrine but a set of principles centered on loyalty, discipline, courage, and ethical conduct. These values were shaped by a blend of Shinto, Confucian, and Buddhist influences, creating a code that governed not only a samurai’s actions in battle but also his daily life, relationships, and death.

The key pillars of bushido included:

- Loyalty: Total dedication to one’s lord, even to the point of death.

- Courage: A samurai was expected to face danger and death without hesitation.

- Benevolence: Warriors were encouraged to act with compassion and protect the weak.

- Respect: Treating all individuals, even adversaries, with dignity.

- Integrity: Upholding truth and honesty in all interactions.

- Honor: A samurai’s honor was paramount, and any stain on it was seen as worse than death.

- Self-discipline: Mastery over one’s emotions and desires was considered essential to achieving true warrior status.

Bushido was not just about fighting; it was a way of life that encouraged personal growth, ethical conduct, and the pursuit of wisdom. It cultivated a sense of responsibility not only to one’s lord but to society and the samurai's role in upholding order and justice.

Honor and Loyalty

Loyalty was perhaps the most sacred virtue in bushido, deeply intertwined with the concept of honor. A samurai’s loyalty to his lord, or daimyo, was absolute. This relationship was built on a bond of trust, where the samurai would serve their lord without question, even if it meant sacrificing their own lives. Such loyalty was often expressed in battle, where samurai were expected to fight with valor and never show cowardice, as doing so would bring dishonor to both themselves and their lord.

Honor, in the samurai's worldview, was so critical that the loss of it was considered worse than death. To die in service to one's lord or in the pursuit of a noble cause was the ultimate fulfillment of bushido. On the other hand, to live with disgrace was intolerable. If a samurai failed in his duty or dishonored himself, he was expected to commit seppuku—ritual suicide—rather than live in shame. This act of seppuku was seen as a way to restore one’s lost honor, demonstrating that a samurai’s commitment to his principles outweighed his attachment to life.

Connection to Zen Buddhism

Zen Buddhism played a significant role in shaping the mental discipline and stoicism that defined the samurai spirit. Introduced to Japan in the 12th century, Zen emphasizes meditation, mindfulness, and the impermanence of life—concepts that resonated deeply with the samurai, who often faced death in battle.

Zen practice helped samurai develop a calm, focused mind, essential for mastering both the martial arts and the unpredictability of life and death. Through meditation, samurai cultivated inner peace, which allowed them to act decisively without hesitation or fear of death. This detachment from the fear of mortality enabled them to face their enemies with a clear mind, which was critical in combat situations where swift, intuitive action was often the difference between life and death.

Additionally, Zen’s teachings on simplicity and self-control mirrored the samurai's ascetic lifestyle, emphasizing discipline over indulgence and humility over pride. The Zen influence also led many samurai to seek enlightenment through the pursuit of artistic and cultural practices like tea ceremonies, calligraphy, and poetry, balancing their warrior ethos with a refined sense of beauty and contemplation.

In this fusion of bushido and Zen, the samurai cultivated an extraordinary blend of martial strength, ethical clarity, and inner calm—a way of life that continues to inspire admiration and intrigue today.

Samurai Store ⚔️

-

Samurai Shirts

Channel the Spirit of the Warrior with Our Samurai Shirts In the...

-

Samurai Hoodies

Samurai Hoodies - Embrace the Warrior Within Dive into the world of...

-

Samurai Masks

🛡️⚔️ Samurai Masks: Battle-Ready Aesthetic Drip From the Age of the Warrior...