Torii Gate

Share

A torii (Japanese: 鳥居) is a traditional Japanese arch most commonly found at the entrance or inside a Shinto shrine, where it symbolically marks the transition from the profane to the sacred.

The presence of a torii at the entrance is often the simplest way to identify Shinto shrines, and a small torii icon depicts them on Japanese road maps.

The earliest appearance of torii gates in Japan can be reliably traced to at least the middle Heian period; they are mentioned in a text written in 922. The oldest extant stone torii was built in the 12th century and belongs to a Hachiman shrine in Yamagata prefecture. The oldest extant wooden torii is a ryōbu torii (see description below) at Kubō Hachiman shrine in Yamanashi prefecture built in 1535.

Torii gates were traditionally made of wood or stone, but today they can also be made of reinforced concrete, copper, stainless steel, or other materials. They are usually unpainted vermilion or painted with a black top lintel.

Inari shrines usually have many torii because those who have been successful in business often donate in gratitude a torii to Inari, kami of fertility and industry. Fushimi Inari-taisha in Kyoto has thousands of such torii, each bearing the name of the donor.

Torii Gate Etymology

A "torii" at the entrance to Tatsuta Shrine, a Shinto shrine in Sangō, Nara.

See also Indian world, Indianization of Southeast Asia, Indosphere, and Shinto.

Torii, a gateway erected at the entrance to each Shinto shrine, may be derived from the Indian word torana. While the Indian term denotes an entrance gate, the Japanese characters can be translated as "bird's perch. "

Ancient Indian torana sacred gateway architecture has influenced gateway architecture throughout Asia, especially where Buddhism was transmitted from India; Chinese paifang gateways, Japanese torii gates, Korean Hongsalmun gateways, and Sao Ching Cha in Thailand have been derived from the Indian torana.

The functions of all are similar, but generally differ according to their respective architectural styles. According to several scholars, the vast evidence shows how torii, both etymologically and architecturally, were originally derived from the torana, a separate sacred ceremonial gate marking the entrance to a sacred precinct, such as a Hindu-Buddhist temple or shrine, or city.

Bernhard Scheid wonders whether torii existed in Japan before Buddhism or whether they came with them from India.

Uses of Torii Gate

The function of a torii is to mark the entrance to a sacred space. For this reason, the path leading to a Shinto shrine (sandō) almost always straddles one or more torii, which are thus the easiest way to distinguish a shrine from a Buddhist temple. If the sandō passes under multiple torii, the outside of them is called ichi no torii (一の鳥居, first torii).

The next ones, closer to the shrine, are usually called, in order, ni no torii (二の鳥居, second torii) and san no torii (三の鳥居, third torii). Other torii can be found further inside the shrine to represent increasing levels of sanctity as one approaches the inner shrine (honden), the core of the shrine.

In addition, because of the strong relationship between Shinto shrines and the Japanese imperial family, there is also a torii in front of each emperor's tomb.

In the past, the torii must also have been used at the entrance to Buddhist temples. Even today, a temple as prominent as Osaka's Shitennō-ji, founded in 593 by Shōtoku Taishi and the oldest state-built Buddhist temple in the world (and the country), has a torii straddling one of its entrances.

(The original wooden torii burned down in 1294 and was later replaced by a stone one).) Many Buddhist temples include one or more Shinto shrines dedicated to their tutelary kami ("Chinjusha"), and in that case a torii marks the entrance to the shrine. Benzaiten is a syncretic goddess derived from the Indian deity Sarasvati, who unites elements of both Shinto and Buddhism.

For this reason, halls dedicated to her can be found in both temples and shrines, and in both cases, in front of the hall, there is a torii. The goddess herself is sometimes depicted with a torii on her head. Finally, until the Meiji period (1868-1912), torii were usually adorned with plaques with Buddhist sutras.

Yamabushi, ascetic hermits in the Japanese mountains with a long tradition as mighty warriors endowed with supernatural powers, sometimes use a torii as a symbol.

The torii is also sometimes used as a symbol of Japan in non-religious contexts. For example, it is the symbol of the Marine Corps Security Force Regiment and the 187th Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division and other U.S. forces in Japan.

Torii Gate Origins

The origins of the torii are unknown and there are several different theories on the subject, none of which have gained universal acceptance.18 Because the use of symbolic doors is widespread in Asia (such structures can be found, for example, in India, China, Thailand, Korea, and within Nicobarese and Shompen villages), historians believe that they may be an imported tradition.

They may, for example, have originated in India from the torana gates at the Sanchi monastery in central India. According to this theory, the torana was adopted by the founder of Shingon Buddhism, Kūkai, who used it to demarcate the sacred space used for the homa ceremony.

The hypothesis arose in the 19th and 20th centuries because of similarities in structure and name between the two gates. Linguistic and historical objections have now arisen, but no conclusion has yet been reached.

In Bangkok, Thailand, a Brahmin structure called Sao Ching Cha looks very much like a torii. Functionally, however, it is very different in that it is used as a swing. During ceremonies, Brahmins swing, trying to grab a bag of coins placed on one of the pillars.

Other theories claim that the torii may be related to the pailou of China. However, these structures can assume a wide variety of forms, only some of which actually look somewhat like a torii.

The same is true of the Korean "hongsal-mun". Unlike its Chinese counterpart, the hongsal-mun does not vary much in design and is always painted red, with "arrows" located at the top of the structure (hence the name).

There are several tentative etymologies of the word torii. According to one, the name derives from the term tōri-iru (通り入る, to pass through and enter).

Another hypothesis takes the name literally: the gate originally would have been a kind of bird perch. This is based on the religious use of bird perches in Asia, such as Korean sotdae (솟대), which are poles with one or more wooden birds resting on top.

Commonly found in groups at the entrance of villages along with totem poles called jangseung, they are talismans that ward off evil spirits and bring good luck to villagers. "Bird perches" similar in form and function to sotdae also exist in other shamanic cultures in China, Mongolia and Siberia.

Although they do not resemble torii and serve a different function, these "bird perches" show how birds in various Asian cultures are believed to have magical or spiritual properties and, therefore, may help explain the enigmatic literal meaning of the torii's name ("bird perch").

Poles believed to have held wooden bird figures very similar to sotdae have been found along with wooden birds, and some historians believe that they somehow evolved into today's torii. Interestingly, in both Korea and Japan the individual poles represent deities (kami in the case of Japan) and hashira (柱, pole) is the kami counter.

In Japan, birds have also long had a connection with the dead, this may mean that they were born in connection with some prehistoric funeral rite. Ancient Japanese texts such as the Kojiki and the Nihonshoki, for example, mention how Yamato Takeru after his death became a white bird and thus chose a place for his own burial.

For this reason, his mausoleum was called shiratori misasagi (鳥陵, white bird tomb). Many later texts also show some relationship between dead souls and white birds, a common link also in other cultures, shamanic as the Japanese.

Bird motifs from the Yayoi and Kofun periods associating birds with the dead have also been found in several archaeological sites. This relationship between birds and death would also explain why, despite its name, no visible trace of birds remains on the torii today: birds were symbols of death, which in Shinto brings pollution (kegare).

Finally, the possibility that the torii are a Japanese invention cannot be ruled out. The first torii could have already evolved with its current function through the following sequence of events:

- Four poles were placed at the corners of a sacred area and connected with a rope, thus dividing the sacred and the profane.

- Then two taller poles were placed in the center of the most auspicious direction, to let the priest enter.

- A rope was tied from one pole to the other to mark the boundary between the outside and the inside, the sacred and the profane. This hypothetical stage corresponds to a type of torii in actual use, the so-called shime-torii (注連鳥居), an example of which can be seen in front of the haiden of the Ōmiwa shrine in Nara

- The rope was replaced by a lintel.

- Because the gate was structurally weak, it was reinforced with a tie beam, and what is today called shinmei torii (神明鳥居) or futabashira torii (二柱鳥居, two torii pillars) was born. However, this theory does nothing to explain how the gates got their name.

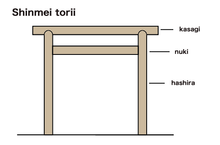

The shinmei torii, whose structure agrees with the historians' reconstruction, consists of only four uncut and unpainted logs: two vertical pillars (hashira (柱)) topped by a horizontal lintel (kasagi (笠木)) and joined by a connecting beam. (nuki (貫)). The pillars may have a slight inward slant called uchikorobi (内転び) or simply korobi (転び). Its parts are always straight.

Torii Gate Parts and ornamentations

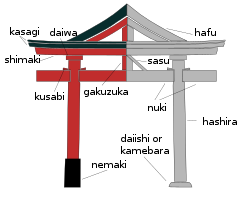

- Torii may be unpainted or painted vermilion and black. The black color is limited to kasagi and nemaki (根巻, see illustration). Very rarely, torii can also be found in other colors. The Kamakura-gū of Kamakura, for example, has one white and one red.

- The kasagi may be reinforced underneath with a second horizontal lintel called shimaki or shimagi (島木).

- Kasagi and the shimaki may have an upward curve called sorimashi (反り増し).

- The nuki is often held in place by wedges (kusabi (楔)). The kusabi in many cases are purely ornamental.

- In the center of the nuki may be a supporting prop called a gakuzuka (額束), sometimes covered by a tablet bearing the name of the shrine

- The pillars often rest on a ring of white stone called kamebara (亀腹, turtle belly) or daiishi (台石, base stone). The stone is sometimes replaced by a decorative black sheath called nemaki (根巻, root sheath).

- On top of the pillars there may be a decorative ring called daiwa (台輪, large ring).

- The gate has a purely symbolic function and therefore there are usually no wooden gates or fences, but there are exceptions, as for example in the case of the triple-arched torii of the Ōmiwa Shrine.

Torii Gate Styles

Structurally, the simplest is the shime torii or chūren torii (注連鳥居) Probably one of the oldest types of torii, it consists of two poles with a sacred rope called shimenawa tied between them.

All other torii can be divided into two families, the shinmei family (神明系) and the myōjin family (明神神系). Torii of the former have only straight parts, the latter have straight and curved parts.

Shinmei family

Shinmei torii and its variants are characterized by straight upper lintels.

Shinmei torii

The shinmei torii (神明鳥居), after which the family is named, consists only of a lintel (kasagi) and two pillars (hashira) joined by a connecting beam (nuki). In its simplest form, the four elements are rounded and the pillars have no slant. When the nuki has a rectangular cross-section, it is called Yasukuni torii, from Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo. It is believed to be the oldest torii style.

Ise torii

伊勢鳥居 (Ise torii) (see illustration above) are gates found only at the Inner Shrine and Outer Shrine at Ise Shrine in Mie Prefecture. For this reason, they are also called Jingū torii, from Jingū, the official Japanese name for the Ise Grand Shrine.

There are two variants. The more common one is extremely similar to a shinmei torii, however, its pillars have a slight inward slant and its nuki is held in place by wedges (kusabi). The kasagi has a pentagonal cross-section (see illustration in the gallery below). The ends of the kasagi are slightly thicker, giving the impression of an upward slant. All of these torii were built after the 14th century.

The second type is similar to the first, but also has a secondary rectangular lintel (shimaki) below the pentagonal kasagi.

This and the shinmei torii style began to become more popular in the early 20th century in the State Shinto era because they were considered the oldest and most prestigious.

Kasuga torii

The Kasuga torii (春日鳥居) is a myōjin torii (see illustration above) with straight upper lintels. The style takes its name from the ichi-no-torii (一の鳥居) of Kasuga-taisha, or main torii.

The pillars have a slant and are slightly tapered. The nuki protrudes and is held in place by a kusabi inserted from both sides.

This torii was the first to be painted vermilion and to adopt a shimaki at Kasuga Taisha, the shrine from which it takes its name.

Hachiman torii

Almost identical to a kasuga torii (see illustration above), but with the top two lintels slanted, the Hachiman torii (八幡鳥居) first appeared during the Heian period. The name comes from the fact that this type of torii is often used at Hachiman shrines.

Kashima torii

The kashima torii (鹿島鳥居) (see illustration above) is a shinmei torii without korobi, with kusabi and a protruding nuki. It takes its name from Kashima Shrine in Ibaraki Prefecture.

Kuroki torii

The kuroki torii (黒木鳥居) is a shinmei torii constructed of unpeeled wood. Because this type of torii requires replacement at three-year intervals, it is becoming rare. The most notorious example is Nonomiya Shrine in Kyoto. However, the shrine now uses a torii made of synthetic material that simulates the appearance of wood.

Shiromaruta torii

The shiromaruta torii (白丸太鳥居) or shiroki torii (白木鳥居) is a shinmei torii made from logs that have had their bark removed. This type of torii is present in the tombs of all the emperors of Japan.

Mihashira torii

The mihashira torii or Mitsubashira Torii (三柱鳥居, Three-pillar torii, also 三角鳥居 sankaku torii) (see illustration above) is a type of torii that appears to consist of three individual torii (see gallery). It is believed by some to have been built by early Japanese Christians to represent the Holy Trinity.33

Myōjin family

The Myōjin torii and its variants are characterized by curved lintels.

Myōjin torii

The myōjin torii (明神鳥居), by far the most common torii style, are characterized by curved upper lintels (kasagi and shimaki). Both curve slightly upward. Kusabi are present. A myōjin torii may be made of wood, stone, concrete or other materials and be vermilion or unpainted.

Nakayama torii

The Nakayama torii style (中山鳥居), which takes its name from Nakayama Jinja in Okayama Prefecture, is basically a myōjin torii, but the nuki does not protrude from the pillars and the curve formed by the top two lintels is more accentuated than usual. The torii at Nakayama Shrine that gives the style its name is 9 m high and was erected in 1791.

Daiwa / Inari torii

The daiwa or Inari torii (大輪鳥居・稲荷鳥居) (see illustration above) is a myōjin torii with two rings called daiwa on top of the two pillars. The name "Inari torii" comes from the fact that vermilion daiwa torii tend to be common at Inari shrines, but even at the famous Fushimi Inari-taisha Shrine not all torii are of this style. This style first appeared in the late Heian period.

Sannō torii

The sannō torii (山王鳥居) (see photo below) is myōjin torii with a pediment over the top two lintels. The best example of this style is found at Hiyoshi Shrine near Lake Biwa.

Miwa torii

Also called sankō torii (三光鳥居, three light torii), mitsutorii (三鳥居, triple torii) or komochi torii (子持ち鳥居, torii with children) (see illustration above), the miwa torii (輪鳥居) is composed of three myōjin torii without pillar leaning. It can be found with or without gates. The most famous one is found at Ōmiwa Shrine in Nara, from which it takes its name.

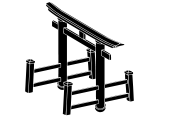

Ryōbu torii

Also called yotsuashi torii (四脚鳥居, four-legged torii), gongen torii (権現鳥居) or chigobashira torii (稚児柱鳥居), the ryōbu torii (両部鳥居) is a daiwa torii whose pillars are reinforced on both sides by square posts (see illustration above).

The name derives from its long association with Ryōbu Shintō, a school of thought within Shingon Buddhism. The famous torii rising from the water at Itsukushima is a ryōbu torii, and the shrine used to be a Shingon Buddhist temple as well, so much so that it still has a pagoda.

Hizen torii

The hizen torii (肥前鳥居) is an unusual type of torii with a rounded kasagi and pillars that widen downward. The example in the gallery below is the main torii in Chiriku Hachimangū in Saga Prefecture, and an important cultural property designated by the city.