Japanese Meisho-e: Exploring the Art of Famous Places

Share

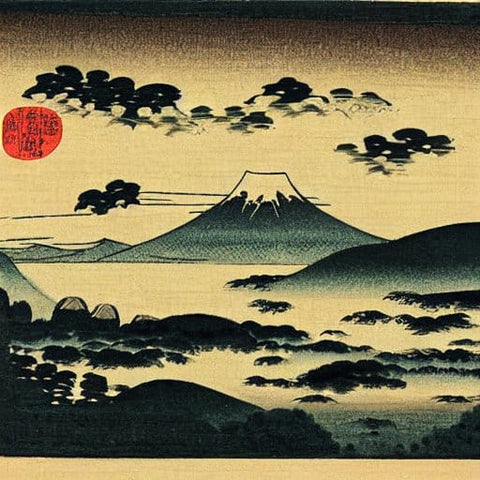

Meisho-e (名所絵, lit. "painting of famous views") refers to Japanese paintings of "famous views" of the archipelago. Influenced by China, this theme became important in Japan in the medieval period (around the 10th and 14th centuries) and continued between the 16th and 19th centuries in Momoyama-era decorative painting, the Rinpa school, and ukiyo-e thereafter.

If the famous views are centered on the landscapes of the archipelago, the motives are in reality more varied and can be interested in depicting the daily life of the people or religious practices.

The meisho-e consists in identifying and representing in pictorial form the most famous characteristics of a place known for its beauty or its interest, in order to identify it easily, by symbolism or realism. It is more generally a genre that can mix seasonal painting, landscape painting and poetry.

History of meisho-e

Yamato-e : birth of meisho-e of Japanese taste

Japan discovered and learned about landscape painting from China; the oldest preserved landscapes are in the Hōryū-ji and date from the Asuka period (6th century).

Later in the Heian period (ninth and eleventh centuries), the development of yamato-e favored secular paintings with Japanese subjects, as opposed to paintings with Chinese subjects named kara-e. The imperial court of Heian-kyō appreciated paintings on screens that illustrated a waka poem (byōbu uta), evoking Buddhism, the impermanence of things, the four seasons, or rites and ceremonies; the symbolisms linking poetry and seasons provided many pictorial motifs, for example the cherry blossoms of Mount Yoshino associated with spring.

Very often, places known for their beauty around the capital (then Heian) are used to illustrate these themes, being depicted in a particular season and inspired by a waka poem; it is thus around the ninth or tenth century that these paintings of famous places, or meisho-e, appear.

Poetry seems to have played a key role in the early development of the genre; in 1207, for example, Emperor Go-Toba selected forty-six famous sights as subjects for waka poems, which were then to be transposed into images on the sliding partitions of the Saishōshitennō-in monastery. The works were often the result of the work of the Emperor, and the poems were often used as the basis for the paintings. Often, the works were the product of the painter's imagination or inspired by a poem, without any realism, especially for remote places in Japan.

As in poetry, what was important was the emotional or evocative force associated with a place, which one had to be able to identify by convention, stereotype or pictorial tradition; the poetic or plastic motifs associated with a place (utamakura) were very numerous and codified: for example, a barrier girded with red-leafed trees designates the Shirakawa barrier, associated with the autumn wind.

The Japanese subject of yamato-e painting is characterized by a more lyrical and decorative composition than their Chinese counterparts which seek spiritual grandeur. The artists prefer soft landscapes, with rounded hills and trees in blue and green colors. However, none of these early works have come down to us; the earliest known painting of this type is a six-panel landscape screen in the sinister kara-e style. The traditional supports for meisho-e are screens (byōbu), sliding partitions (fusuma) or palace or temple walls.

During the Kamakura period, meisho-e, like all Japanese art, were marked by the new realist and naturalistic trends brought about by the rise to power of the samurai (bakufu) and the development of the Buddhist schools of the Pure Land, a desire for realism that departed from hitherto elementary poetic conventions. The preferred medium of the time was emaki (long painted narrative scrolls telling the story of novels, historical chronicles or monks' biographies). The realistic, almost life-like landscapes of the Ippen shōnin eden (thirteenth-century emaki) are highly regarded for their accuracy. The work features one of the earliest and most detailed depictions of the landscape in the world. Notably, the work features one of the earliest known paintings of Mount Fuji. The Saigyō monogatari emaki provides various famous views inspired by Saigyō Hōshi's wakas poems in an idealized, spare line.

A few paintings draw their inspiration from Shinto instead: the thirteenth-century kakemono depicting the famous Nachi waterfall (supposedly the emanation of a kami) conveys a real animistic force.

Wash

The painting of the Muromachi period, marked by Zen, saw the emergence of the pictorial movement of the monochrome wash (suiboku-ga or sumi-e); anonymous landscape compositions became powerful, lyrical and spiritual, marked by the vigor of the brush. A famous meisho-e is Sesshū's View of the Ama-no-Hashidate, painted in 1501, where the line respects rigorous topographical precision (the Amanohashidate is one of the three most famous views in Japan); there are a few other copies of famous views by Sesshū.

Kanō Tannyū (Kanō school), responsible for the murals in Edo and Nijō castles, painted several famous views there.

Series of ukiyo-e prints

Travel within Japan expanded with the Edo period and the pacification of the country that it brought. While most of these trips were necessitated by political, or economic, imperatives, travel for pleasure also developed at this time, seeing the appearance of travel guides (meisho ki) and a whole literature, of which the most famous work remains the Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige by Jippensha Ikku. After literature and guidebooks, the image gradually developed in ukiyo-e prints in the nineteenth century, thanks in particular to Hokusai and Hiroshige, who multiplied the series of meisho-e prints from the 1830s. Hokusai experimented with the genre with his Eight Views of Edo in the Dutch Style, where his European influences are evident; the success of his series of Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji gave the landscape print genre a prominent place in the nineteenth century. While Hokusai's art is not a new phenomenon, it is one of the most important. If Hokusai's art is animated by a spiritual style with analytical compositions, his young "competitor" Hiroshige presents works marked by sensitivity and the preponderance of the human. His best-known series are The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō, and The Hundred Views of Edo.

During the Edo period, artists such as Ike no Taiga developed in parallel shinkei ("real views") painting, inspired by China, where landscapes were painted in a very naturalistic and accurate way on the spot. This movement is part of the nan-ga genre.

This concept of the "famous view" in the nineteenth century, where the best vantage points for contemplating an admired place are sought, is probably related to what is found in China: for example, in the imperial summer palace in Chengde, the ancient Jehol, the great Qing emperors Kangxi and Qianlong had dotted the palace grounds with pavilions, known today as the "4th Qianlong Emperor's Viewpoint." The total number of viewpoints in Chengde is seventy-two (two times thirty-six).

Modern era

By the end of the 19th century, the ukiyo-e movement was in decline. The "famous views" remained, however, a subject of inspiration through photography, for example certain works by Adolfo Farsari.

Derived pictorial currents

Some pictorial currents are close to the meisho-e genre:

- Shinkei-zu: literally "paintings of real views," a type of naturalistic landscape in vogue during the Edo period inspired by wash landscapes.

- Meisho zue: travel guides illustrated with scenes from famous views;

- Rakuchū-rakugai-zu: views in and around Kyoto (or Heian, the ancient capital of Japan).

Main themes of meisho-e

The seasons

Meisho-e were originally very much related to the so-called season paintings (shiki-e), often depicting a place at one or more seasons of the year. The murals in the Hōō-dō (Phoenix Pavilion) of the Byōdō-in form a masterpiece of the genre in the xieme century: each wall depicts a season in a style typical of the yamato-e of the Heian period. This principle was to be found long afterwards in the series of ukiyo-e prints.

For Saburō Ienaga, the almost systematic presence of the four seasons makes classical meisho-e a particular variation of shiki-e, the combination of landscapes and genre painting appears to be characteristic of the yamato-e style in general.

The human

The human in meisho-e and landscape paintings characterizes the art of Japan, where the anecdotal presence of the people (peasants, travelers, city dwellers, pilgrims, warriors...) remains very common. For Akiyama Terukazu, humanizing nature appears to be the "essential basis of Japanese aesthetics. The art of Hiroshige, for example, depicts the activities of the people with the sensitivity of a poet; a famous print depicts passers-by surprised by rain on the Ohashi Bridge (see) in the Hundred Views of Edo.

Views of Kyoto

In the medieval period, Heian-kyō (now Kyoto) was the center of artistic circles, whether at the imperial court or in the great temples. In fact, the first famous views were directly inspired by the surroundings of the capital: Sagano, Osaka barrier, Akashi beaches, cherry blossoms of Mount Yoshino, Musashino.

From the sixteenth century onwards, another type of painting appeared, inspired by classical meisho-e, called rakuchū-rakugai-zu (洛中洛外図, literally "views outside and inside the capital"), usually on a panel or screen. A very distant viewpoint is used to depict the daily activities in the capital (rakuchū) as well as the surroundings of the city (rakugai) in one set. The first version (six-panel Machida screen) from the sixteenth century is typical of Momoyama (Rimpa school) painting, with its rich colors, intense use of gold, and mists. These views are often meticulous in depicting the daily life of the people (festivals, markets, entertainment...).

Five Edo Roads

During the Edo period, five major roads (Gokaidō) connected the new capital to other cities in Japan, including the Tōkaidō and the Kiso Kaidō to Kyoto. Lined with numerous stops or stations and crossing a wide variety of regions, they offer many sources of inspiration for the masters of ukiyo-e prints, who transcribe both grandiose landscapes and popular activities in the lively or remote regions of Japan. The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō by Hiroshige or The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō by Hiroshige and Eisen are the best known examples of these series of prints.

Technique

Traditionally, Western-style realistic perspective does not exist in Japanese painting. Instead, each element in the painting takes on the importance it occupies in the painter's mind, freeing himself from the rigorous rules of perspective practiced in the West. The distant views do not prevent the representation of characters as large as buildings or trees, for example. The idea of depth is rendered instead by long parallel lines and pictorial devices, such as winding paths or flights of birds disappearing on the horizon. The mists allow for a gentle separation of the different planes. Around the Edo period, realistic European perspective gradually became established in Japanese painting in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (uki-e).

The colors of the meisho-e are linked to the dominant pictorial trends in Japanese art:

- in the early medieval period, the so-called "blue and green" or "blue and red" landscapes inspired by Chinese shanshui were widely used, as were the opaque mineral or vegetable pigments (diluted in animal glue) of yamato-e.

- in the Muromachi period, monochrome washes inspired by Zen dominated;

- in the Azuchi Momoyama period, the colors are rich, heavy and predominantly golden (dami-e);

- In the Edo period, ukiyo-e was marked by a wider palette of shades (nishiki-e) as well as the recurrent use of Prussian blue in the landscape series.