Japanese Castle

Share

Japanese castles (城 shiro) were fortifications built primarily of stone and wood. These evolved from the wooden buildings of earlier centuries to the better-known forms that emerged in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, following the example of Azuchi Castle, built by Oda Nobunaga, and the first of its kind to use stone at the base of the castle, making it more sturdy.

In the same way as castles in other parts of the world, Japanese castles were built to guard strategic or important places such as ports, rivers, or roads and almost always took into account the characteristics of the place for its best defense.

Japanese castles experienced several stages of destruction. During the Tokugawa shogunate a law was decreed to limit the number of castles that each daimyō or feudal lord could own, limiting it to one per fief, so several were destroyed.

After the fall of the shogunal system and the return to power of the Emperor of Japan during the Meiji Restoration, again many castles were destroyed and some others dismantled, in an attempt to break with the past and modernize the country.

During World War II many castles were destroyed during bombing raids in the Pacific coastal regions and only a few castles located in remote areas, such as Matsue Castle or Matsumoto Castle remained intact.

After World War II, many castles have been rebuilt with modern materials, such as concrete, although in a few of them the original materials have been used and following the same technique as in their time of splendor.

Today, only twelve castles still retain their original structure, with Himeji Castle, located in Hyōgo Prefecture, standing out. Of the existing castles, whether original, reconstructed or in ruins, many have received Unesco World Heritage Site status, while others have been designated National Treasures.

Today many castles have become museums and house objects of regional importance, telling the history of the cities where they are located.

Japanese Castle Etymology

In Japanese, the kanji used for the word castle is 城, which is read as shiro according to Kun'yomi pronunciation, that is, when the kanji is not accompanied by another, or jō according to On'yomi or when it is part of a word. An example is Kumamoto-jō (熊本城) or Kumamoto Castle.

In English, to refer to a castle, the jō ending is omitted, mentioning only its name. Another important aspect to consider is that generally castles are named according to the city, region or prefecture in which they are located. For example, Gifu Castle is located in the city of the same name, as is Komoro Castle, Hiroshima Castle, etc.

Japanese Castle History

Early fortifications

Yayoi Period

The earliest fortifications in Japan date back to the Yayoi period (300 BC - 300 AD), a period characterized by the expansion of rice cultivation as well as the introduction of metals (first iron and later bronze) to the archipelago by immigrants from mainland Asia.

The Yayoi culture communities began to grow and displaced the natives, so fortifications were built to protect their interests and settlements. The first fortifications were built on high ground to serve as lookout posts in case of attacks.

In addition to archaeological evidence, ancient records from China concerning Japan, formerly known in Japan as Wa, mention the construction of fortifications in this period. The earliest record on this subject is found in the Wei Zhi, which documents the history of the Wei Dynasty (220 - 265 AD). Another important record is in the Hao Hanshu, compiled around 445 AD.

During surveys of ancient settlements of the period, such as those found at Otsuka near Yokohama and Yoshinogari in Kyūshū, it has also been discovered that some settlements were protected by dykes, even those located on elevated sites.

Yamato Period

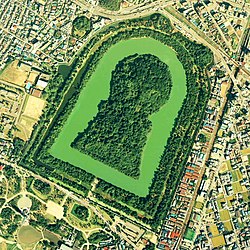

The Daisenryō-Kofun, in Osaka, is the largest tomb of this type and its construction dates to the 5th century AD.

The development of the Yayoi culture culminated in the establishment of a unified state now known as Yamato, established by a dominant lineage that would eventually become the imperial house.

The dominance over their opponents of the Yamato court, settled in what is now Nara Prefecture, resulted in the absence of fortifications from the 300s onwards, with the construction of Kofun; large burial mounds developing in their place.

Attention to fortifications resurfaced around 664, after an expeditionary force departed Japan in an attempt to aid their Paekche allies against the coalition formed by the Silla Kingdom and the Tang Dynasty.

After a resounding defeat in 663, where some 10,000 soldiers were killed, the inhabitants of Japan began to worry about a possible invasion by China or Korea, so Emperor Tenchi, according to the Nihon Shoki, decreed that the necessary defenses be erected on the islands of Tsushima and Iki, as well as on the lands of Tsukushi, to protect themselves in case of an invasion.

Notable among the buildings constructed for this purpose was the Mizuki (水城 "water castle"), a large building 40 meters long by 15 meters high with moats, its purpose was the defense of the barracks located on Dazaifu.

After the construction of this fortification, mostly preserved to this day, fortifications that can be identified more with the current castle concept began to be built, first along Kyūshū and then inland to the Yamato control center, as far as what corresponds to Nara today.

The style of such fortifications is distinctly Korean, due to the fact that it was Paekche refugees who carried out the construction. One example is the construction of Ki Castle, built by Ongye Pongnyu, who escaped with the survivors of the defeat of 663 and as a token of gratitude collaborated in the construction of castles in Japan based on the model of the Korean sanseong or castles.

The fortifications erected in that period were maintained and repaired for approximately four decades, until the situation normalized in Asia due to the withdrawal of the Tang dynasty from Korea, a peninsula that was ruled by Silla, which removed the possibility of an invasion of Japan.

From that moment on, the Yamato court focused its attention on the northeast of the country, on the tribes that resisted the central mandate and that were identified as Emishi. Attempts to subjugate the Emishi began around the second half of the seventh century, so along with military campaigns, various wooden fortifications were established in the north of the country.

In Echigo province two fortifications were built in 647 and 648, a practice that would continue for two more centuries in the provinces of Mutsu and Dewa as the Yamato frontier advanced. During this period the fortifications served not only military purposes, but were true centers of imperial administration.

In 774, once fortifications of great size and strategic importance had been built, a large-scale campaign of "pacification" of the area began that would last forty years, with major expeditions in 776, 788, 794, 801, and 811, after which the pacification mission was declared successfully completed.

Heian Period

Japan's first permanent capital was established in Nara in 710, but was soon abandoned and moved to Kyoto in 794, marking the beginning of the Heian period, which was characterized by a series of wars and revolts culminating in the Genpei Wars of 1180-1185.

During this period, temporary watchtowers and palisades were built in the face of impending conflict, especially around the capital. One example of these palisades was Kuriyagawa, a large defensive complex that was besieged in 1062 during the Zenkunen War or "Nine Years' War.

In 1192 Minamoto no Yoritomo was appointed the first hereditary shōgun after the Minamoto clan defeated the Taira during the Genpei Wars, one of the most important victories for Yoritomo being that of Ichi-no-Tani, a major coastal fortress dominated by the Taira in Harima province, west of present-day Kōbe.

Kamakura Period

Yoritomo's triumph led to the establishment of the first shogunate or military dictatorship in Japan, and also meant that the capital was moved to Kamakura, from which this period takes its name. Kamakura was then fortified, an unusual practice in the country's history.

The use of stone in fortifications or castles was practically nil, only rarely employed after the Mongol invasions of Japan. Kublai Khan, Yuan ruler of China launched a first invasion attempt in the year 1274, although the confrontation was brief, and practically the same day they landed they returned to China.

This experience led the Japanese to build stone walls around Hataka Bay, where the invading forces had landed. When the Mongols returned in 1281 these walls served as a base for the defending archers.

During the Nanbokuchō Wars of the 14th century, important castles were built, predominantly of wood and on top of mountains, taking advantage of the orography of the site to improve their defenses. Two outstanding castles of the period are Akasaka Castle and Chihaya Castle, both defended by the samurai Kusunoki Masashige.

Sengoku period

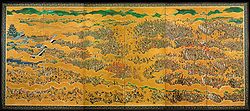

The Ōnin War that broke out in 1467 marked the beginning of the so-called Sengoku period; an era of about 150 years of continuous warfare between daimyō (feudal lords) throughout the archipelago.

For the duration of the Ōnin War (1467-1477), the entire city of Kyoto became a battlefield and suffered tremendous damage. The mansions of the nobles began to be fortified within 10 years; in addition, efforts were made to isolate the entire city from the marauding samurai armies that would dominate the landscape for nearly a century.

The country was plunged into war and additional fortifications quickly began to be built to take advantage of or dominate important locations, usually high in the mountains, for which they became known as yamashiro ("Mountain Castles").

Along with the yamashiro then arose fortified mansions known as yashiki (屋敷), which ranged from simple buildings to highly elaborate complexes, around which watchtowers, walls and gates were built. Both structures then became important political and military centers, around which emerged the so-called jōkamachi (城下町 lit. "village under castle").

What are today considered "classical" stereotypes of Japanese castles emerged at this time.

Azuchi-Momoyama Period

The weak point of the castles of the previous period was their bases, generally "sculpted slopes" that forced those responsible for the castles to carry out important maintenance works at least every five years, in addition to not supporting constructions of more than three stories in height.

The solution consisted in arranging wide stone bases that characterize the typical Japanese castle. This solution also provided them with an extremely rigid support against the constant tremors that Japan suffers.

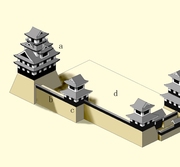

The stone base system did not spread very quickly throughout the country for financial reasons and because daimyō generally did not use only one castle, but it was common for them to have a whole network of satellite castles.In this case, the main castle was called honjō, while the secondary supporting castles were called shijō.

The shijō were usually governed independently of the main castle, with the aim of administering the fief territories; those tasks in the secondary castles were entrusted to members of the ruling family or to trusted vassals loyal to the clan. The shijō could also be miniature replicas of the main castles, with the same stone base and wooden watchtowers.

Finally, the shijō could be supported by fortified palisades along the lines of the ancient yamashiro of the Sengoku period.

The first to develop the use of the stone base in the construction of keep towers or tenshu kaku were the architects of Anō, in the province of Ōmi. Such architects were experienced in the construction of stone bases of pagodas and shrines, and after making trials in the construction of watchtowers, the earliest record of them is from 1577, on the construction of the tenshu of the Tamon Castle of the daimyō Matsunaga Hisahide, although unfortunately nothing survives of it to this day.

Another early tenshu to use a stone base was that of Maruoka Castle, built in 1576 and which remained largely intact until 1948, when it had to be leveled because of an earthquake using original materials. The oldest original tenshu is probably that of Matsumoto Castle, whose construction has been dated to 1597.

During this period, various castles were also built both for defensive purposes and to reflect the wealth of each feudal lord, seeking to impress enemy daimyos.

Examples of such castles are Azuchi Castle, built by Oda Nobunaga and destroyed in 1582 after his death during the Honnōji incident, and Fushimi-Momoyama Castle, built by Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Both fortifications provide their name as a reference to this period in Japan's history.

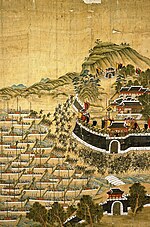

Japanese castles in Korea

During his rule, Toyotomi Hideyoshi ordered the invasion of Korea, leading to a six-year-long conflict. During the war, many Japanese castles (called Wajō 倭城 in Japanese and Waeseong in Korean) were built along the southern coasts of Korea in order to defend their communications.

Because Korean castles were taken extremely easily in the face of the Japanese advance, the invaders decided to create their own castles, elaborately constructed usually by digging into the hills and lining the spaces with large stones to form the fortresses.

Because of their construction, the castles were very short-lived, so that today only a few bases survive throughout the Korean peninsula.

Edo Period and Meiji Restoration

After the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the country was divided into two major factions that clashed in 1600: on one side were the loyalists of the Toyotomi clan, led by Ishida Mitsunari, and on the other the followers of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

The battle, known as the Battle of Sekigahara, marked the beginning of the hegemony of the Tokugawa clan, which ruled until 1868. The rule of the Tokugawa clan is known as the Tokugawa shogunate or Edo period, and began in 1603, when Ieyasu was officially appointed shōgun.

In 1615 the Tokugawa shogunate established a system of regulation for the castles that each daimyō could own. Because of this policy, known as ikkoku ichijō (一国一城 lit. "one province, one castle"), many castles were destroyed or dismantled, and the remaining ones became seats of local administrations.

The Edo period was characterized by a long period of peace, interrupted only by a few internal conflicts, so that Japanese castles also became castle towns, around which the local economy flourished, and would later become the country's present-day cities.

During the mid-19th century, the power of the shōgun declined markedly and numerous pro-imperialist movements arose in the country, so that many castles were once again converted into military bases and some were burned down during revolts.

When the Emperor resumed his leading role in the country's political affairs, castles were seen as possible bases for rebellions (such as the one that occurred during the Satsuma Rebellion and the subsequent siege of Kumamoto Castle)

as well as symbols of an outdated and discredited system, so in 1873 the Law for the Abolition of Castles was enacted, ordering the destruction of many castles, allowing only the towers to be kept for some others.22 In 1875, of the 170 castles that had been built in the Edo period, two-thirds were destroyed.

Japanese Castle In the present day

Reconstruction of ancient castles began as early as 1931, the first being Osaka Castle, followed by Gujō Hachiman Castle in 1933 and Iga Ueno Castle in 1935.

Another stage of castle destruction occurred during World War II, when many were destroyed by bombing of the Pacific coast regions. Only a few castles located in remote areas, such as Matsue Castle or Matsumoto Castle, remained intact.

After the conflict, the intention to rebuild the old castles resurfaced, and since then a large number of them have been erected, mostly to house local museums. The materials used are usually modern materials, such as concrete, so that of the existing castles, only twelve still retain their original construction.

Of the extant castles, Matsumoto, Inuyama, Hikone, and Himeji castles have been named National Treasures (国宝 kokuhō ) by Japan's Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, while Maruoka, Matsue, Marugame, Uwajima, Bitchū Matsuyama, Hirosaki and Matsuyama castles have been designated "Property of Cultural Significance" (重要文化財 jūyō bunka zai ).

Finally, Nijō, Himeji, Nakijin, Naka, and Shuri castles are listed as Unesco World Heritage Sites.

Elements and characteristics of the Japanese castle

All castles of the "developed system" (those with stone bases and building complexes) had certain elements in common.

General arrangement

Right in the heyday of the typical Japanese castle, in the year 1591 Toyotomi Hideyoshi decreed the "Edict of Separation", which sought to formally separate the samurai from the peasants. This edict also affected the organization of the castle towns, since while the soldiers lived inside, the peasants lived outside the town.

During this time, rank within the clan was of utmost importance, since the higher one was in the hierarchical scale, the closer one's own quarters would be to the keep. The most senior servants, or karō, were just outside the main tower and outside were the ashigaru soldiers, only protected by moats or earthen walls. Between the ashigaru and the karō were the artisans and merchants.

Outside the ring formed by the ashigaru's quarters were the temples and shrines, which constituted the boundaries of the castle town. Just outside were the rice fields.

The main common feature of Japanese castles was that the keep towers were located at the highest point of the enclosed castle area, surrounded by a series of intercommunicating palisades. The general term used to refer to the multiple courtyards and enclosed areas formed by this type of layout is called kuruwa (曲輪).

One of the aspects to consider when planning the construction of a castle was to know how those kuruwa would help in the defense of the fortification, which was generally desired based on the topography of the site. The central area of the kuruwa was the most important section in the defensive aspect, and was called the hon maru (本丸 inner citadel).

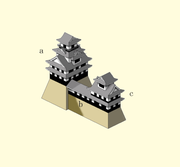

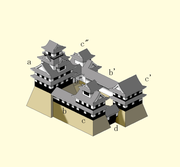

In the hon maru were located the tenshu kaku and other residential buildings for the use of the daimyō. In turn, the second courtyard was called ni no maru (二の丸) and the third san no maru (三の丸). Although in the case of larger castles, surrounding sections called soto-guruwa or sōguruwa could be found, the existing styles are defined by the location of the honmaru.

Japanese Castle Styles

According to the location of the hon maru, three styles can be distinguished:

- Rinkaku style (輪郭式 Rinkaku-shiki):The hon maru is located in the center and the ni no maru and san no maru form concentric rings around it.

- Renkaku style (連郭式 Renkaku-shiki): The hon maru is located in the center, with the ni no maru and san no maru on the sides.

- Hashigokaku style: In the latter style, applied practically only to mountain castles, the hon maru is located at an apex, while the ni no maru and san no maru are descending in the form of a ladder.

Types depending on their location

Depending on their location, Japanese castles can be divided into three types:

- Yamashiro (山城 mountain castle).- This type was the most commonly used in wartime, and was characterized by being built on top of mountains.

- Hirashiro (平城 plain castle).- These were castles built in the middle of plains or plains modeled after Osaka Castle, the first built of this type.

- Hirayamashiro (平山城).- This type of castle was built on low mountains or large hills, locating the castle on a plain.

Walls and ramparts

Successive kuruwa and maru were divided from each other by moats, dykes, smaller walls built on top of stone bases, called dobei (土塀), and stone ramparts, called ishigaki (石垣).

The walls, made of plaster and rocks, often had loopholes called hazama (狭間) whose function was to allow the defenders to attack the besiegers from as protected an interior position as possible. Circular or triangular holes were used for arquebuses, and rectangular holes for arrows.

These walls also had an aesthetic function, so they were painted and decorated with rows of trees and shrubs; usually pines. The large stone bases, which reached heights of up to forty meters, constituted the foundations of the castle. These bases were usually built according to the design of the maru and the kuruwa, joining the bases with a wedge design.

Styles of stone walls

Walls can be classified depending on how they have been arranged. In the Ranzumi style (乱積) stones of different sizes were used without a pattern, while in the Nunozumi style (布積) those of a similar size were used, so they were aligned along the wall.

Types of stone walls

Depending on how worked the stones used in the ishigaki were, the walls can be classified as:

- Nozurazumi (野面積) - Stones were used in their natural state and were not shaped in any way. They were extremely weak, so large walls could not be built. They could also be easily climbed.

- Uchikomihagi (打込ハギ) - The stones were placed tightly against each other, and the face was roughed to make it flat. The resulting small holes were plugged with small stones.

- Kirikomihagi (切込ハギ) - In this type, the stones were carved in such a way that they fit perfectly against each other, so that virtually no holes remained.

Gates

A large number of gates, called Mon (門) in Japanese, existed in Japanese architecture, although they all possessed features in common:

two columns (kagamibashira), usually attached to two pillars (hikaebashira), connected by a lintel (kabuki). The rest of the architectural details depended on their position, function or defensive needs.

Among the different types of gates are:

- Yaguramon (櫓門) - These were gates that had a yagura at the top for the purpose of defending access.

- Yakuimon (薬医門) - These were gates with roofs that covered both the front columns and the rear pillars.

- Koraimon (高麗門) - The front pillars and gates were covered with a roof separate from that covering the rear pillars and supporting beams. This type of gates replaced the Yakuimon.

- Munamon (棟門).- The two main pillars were covered by a roof similar to the koraimon, but without the extra roof.

- Tonashimon (戸無門).- This style is practically a koraimon but without the door.

- Kabukimon (冠木門).- This was a very simple gate consisting of two pillars and a horizontal beam, with a gate but no roof, so it did not serve for defense.

- Heijūmon (塀重門) - Similar type to the kabukimon, but without the horizontal beam.

- Nagayamon (長屋門).- This type of gate spanned large warehouses and warehouses, which were built around it.

- Karamon (唐門) - Ornamental gate with a karahafu-style gable, that is, rounded in the center.

- Uzumimon (埋門 lit. "buried gate") - Constructed either by cutting an opening in the middle of a previously established stone wall, or by leaving a very narrow space for future construction.

- Masugata (枡形) - These were complexes of two gates: usually a koraimon on the outside, and a yaguramon on the inside forming a right angle, and surrounded by walls to create a square enclosed area.

Moats

One of the most important defensive aspects within a castle was its system of moats or hori (堀). Depending on the shape these might have, they could be classified into hakobori (箱堀) or with a "box" shaped bottom, yagenbori (薬研堀 ) or with a "V" shaped bottom, katayangenbori (片薬研堀) or with a straight bottom loaded toward some of its sides, and kenukibori (抜堀) or with a "U" shaped bottom.

In addition to the shape of their bottom, it was common to find water-filled pits called mizuhori (水堀), and dry pits called karabori (空堀).

Usually in addition, structures were built at the bottom of the moats as walls, with the purpose of reducing the enemy army that tried to cross it, creating additional barriers that the invaders would have to circumvent.

All those moats in which only a single row of ridges was built are called unebori (畝堀), while those with more elaborate systems are known as shojibori (障子堀), in a clear allusion to the Japanese paper bearing the same name.

Yagura

In Japanese, the term yagura (櫓 lit. "arrow storehouse ") is used in a generic way to designate the various existing towers. A wide variety of towers existed in Japanese castles. For example, the walled porticoes built in the form of watchtowers are called watari yagura.

Another existing type was the tamon yagura, one-story buildings built in the form of ramparts on stone bases. This construction, in addition to providing a defensive position, could also be set up as an observation center.

Another example of the use of tamon yagura is provided by Hikone Castle, where this building was used to house the servants' quarters.

Another type of tower, called sumi yagura, was built at the corners of the walls, which usually incorporated ishi otoshi, similar to the matachan.

Yagura were also classified depending on what was stored in them, e.g., Teppō yagura (arquebuses), Hata yagura (flags), Yari yagura (spears), Shio yagura (salt), etc., or their functions, such as Taiko yagura (in which a drum was kept), Tsukimi yagura (for observing the moon), and Ido yagura, where a well was housed.

Tower of homage

The first building that was usually observed, before walls or porticoes, was the tenshu kaku (天守閣) or keep, because it was the tallest building and could even be visible from several hundred meters away.

A typical tenshu kaku generally boasted at least three stories in height, with the tallest being seven. An important feature was that the number of floors visible from the outside rarely corresponded to the actual floors, because basements were often built into the stone base.

The function of the tenshu kaku was of paramount importance within the complex, as it was responsible for providing a last line of defense, constituted the image of the ruling daimyō, and provided a secure storage place.

These towers usually had square windows, and the top floor had an exterior balcony. At the top of the building there were often decorations called shachi, either metal or slabs, which were believed to prevent fires and ward off "evil spirits. "

Within the castles that survive to the present day, it has been found that they were generally painted white, although this was not a rule. Some castles such as Azuchi or Osaka were very brightly colored and decorated with tigers and dragons, while on the other hand Kumamoto and Okayama castles were painted black.

The tenshu kaku can be divided by their structure or style.

Classification by structure

According to the structure, keep towers can be divided into two types: borogata and sotogata.

The borogata style (望楼型), present in those castles built when the stone base had not yet been fully developed, are easily recognizable because they feature a hipped roof and gable, a style known as irimoya, which produces the impression that the lower and upper floors were of different styles, or that one tower had been built on top of another building.

The sotogata (層塔型) style is identifiable because all floors show uniformity, with the upper floors being the same shape but smaller. Although small gables can also be found, these are merely decorative and are not necessarily part of the main construction.

- Fukugoshiki (複合式).- The tenshu kaku was directly connected to a yagura or other tower. Present at Matsue Castle.

- Renketsushiki (連結式) - The tenshu kaku was connected to another tower or yagura via a watari yagura. Present at Nagoya Castle.

- Renritsushiki (連立式).- The tenshu kaku, multiple towers and yagura are connected to each other by watari yagura or tamon yagura, so that the hon maru area is completely surrounded. Present at Wakayama Castle.

- Dokuritsushiki (独立式) - In this style the tenshu kaku is completely isolated. Present at Uwajima Castle.

Japanese Castle Measures taken against ninjas

The major daimyō, influenced by the exaggerations of the ninja myth and eager to avoid being killed, adopted various measures in their castles and mansions, many of which persist to this day.Inuyama Castle, for example, had sliding doors at the back of private rooms, where a few guards were always stationed ready to attack.

The castles furthermore were built so that visitors could be watched from the moment they stepped through the outer gate of the complex, and inside, serious measures were taken, such as those at Nijō Castle in Kyoto, where a special floor called uguisubari (鴬張り "nightingale floor"), where it is virtually impossible to walk without the floor squeaking and emitting a sound similar to the song of these birds, thus alerting to the existence of an intruder in the corridors.

Despite all the measures taken, there were few daimyō who did not face assassination attempts, so they lived surrounded by their most trusted generals, who were not separated from their lord at any time. It is even said that at one point Takeda Shingen, an important daimyō of the Sengoku period, recommended that even in intimacy with one's wife, a daimyō should keep a dagger handy.

Japanese Castle War tactics: Siege and defense

Sieges were the most complicated part of samurai battle methods for both attackers and defenders, so political negotiations were usually conducted prior to the confrontation to avoid bloodshed.

During a siege the defenders were first faced with food and water rationing and subsequent starvation, as the attacker's strategy usually focused on blockading the castle to prevent the occupants from receiving reinforcements, supplies and provisions. For this purpose, palisades or fences were built, consisting of bamboo bundles tied to wooden frames around the castle.

At certain distances, a watchtower was usually built to be able to observe inside the castle. The siege was then carried out in a more conventional way: the attackers would shoot protected by bamboo or wooden curtains, while the defenders would do so from holes in the walls.

Victory was achieved by the attackers when the castle was set on fire or the garrison surrendered, either due to famine or disease. On the other hand, the defenders could force the siege to be lifted by the arrival of support troops or when their forces were superior to those of the other army, forcing them to retreat.

Because the use of artillery did not develop in Japan in the same way as in the Western world, it was used on rare occasions, usually not with the intention of knocking down the castle walls or its keep, but as an anti-personnel weapon and with the aim of having a psychological effect on enemy troops.

An extraordinary case of the use of cannons against a castle is during the attack on Osaka Castle, where Tokugawa Ieyasu used cannons of European origin against the castle.

The defender's position was too difficult, so everything was usually decided in open field engagements. When a daimyō retreated to the tower, he usually did so with the intention of regrouping his forces and facing the enemy one last time in battle, the exceptions being the case of Shibata Katsuie and Azai Nagamasa, who died inside the burning castle (at Kitanosho Castle and Odani respectively).

An example of this can be seen in the siege of Fushimi Castle, part of the Sekigara campaign. During that conflict, Torii Mototada, a general under the command of Tokugawa Ieyasu, endured with his men the attack of more than 40,000 soldiers for more than ten days.

After a traitor set fire to the castle tower, with only 200 survivors, Mototada made five counterattacks until only 10 men were left. It was not until then that Mototada and the survivors decided to commit seppuku to avoid being taken alive.

During the Japanese invasions of Korea, important advances in Japanese siege techniques were developed, one of the pioneers being Katō Kiyomasa. Among his inventions was the kikkōsha (turtle wagon), which was pushed up to the walls protecting its occupants from thrown objects.

Japanese Castle in Comparison with the European model

Unlike in Europe, where the implementation of firearms in combat marked the end of the existence of castles, in Japan artillery was never developed, so that castles were only reinforced with the idea of resisting arquebus fire and cavalry charges.

Also, unlike other regions, stone construction was not completely developed in Japan, so it was only used in the bases and not in the construction of castles, which were basically made of wood.

Another aspect to highlight is that, although from the outside the complexes may look similar, since both followed the model of the castle mote, the Japanese castles contained completely indigenous buildings inside.

Japanese Castles and Pillars

Hitobashira (人柱 lit. "human pillar") were to be performed in order to make the spirit of residences or castles, and have been named since ancient times in Japan, being mentioned in the Nihon Shoki, compiled in 720.

The victims to become hitobashira were volunteers, usually warriors who offered themselves as a token of loyalty to their feudal lord. With the building under construction, a hole was dug at the threshold of the residence or castle, or at the position of one of the main pillars. The warrior would then commit seppuku, and over his body the foundations would be laid, thus becoming a protective spirit of the building.

Stories of hitobashira were common during the sixteenth century. One example is the legend of Oshizu, a blind peasant woman who volunteered to appease the kami after it had proved impossible to stabilize the walls of Maruoka Castle.

In exchange for her sacrifice, which occurred in 1576, the daimyō would take her son into his service. After she died buried by the stones, the daimyō forgot his promise, so it is said that the constant flooding of the moat is a consequence of Oshizu's tears, who mourns his son's misfortune.