Irezumi Tattoos

Share

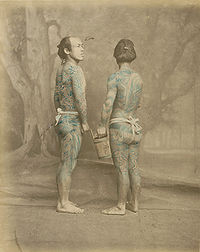

Irezumi (入れ墨, 刺青 or タトゥー) refers to a particular form of traditional tattooing in Japan, which covers large parts of the body, if not its entirety. It can extend from the neck to the bottom of the buttocks, on the chest and on part of the forearms.

The term horimono will be used instead to refer to all styles. Nowadays, irezumi, and tattoos in general, are considered by a majority of Japanese people in a negative way, as being a mark of belonging to the yakuzas, or a macho symbol of the lowest social classes.

Different denominations

The word can be written in a variety of ways, all of which have slightly different connotations. Irezumi is most often written with the Chinese characters 入れ墨 or 入墨, literally "ink insertion".

The characters 紋身 (also pronounced bunshin) suggest "decorating the body." 剳青 has a more esoteric meaning, being written with the characters that mean "remain" or "endure" and "blue" or "green", and probably refer to the main shade of ink under the skin. 黥, meaning tattoo, is rarely used and the characters 刺青 combine the meanings of "pierce", "wound" or "prick" and "blue" or "green" referring to the traditional Japanese method of hand tattooing.

History of Japanese tattoos

Ainu tattoos

Archaeologists have reportedly found terracotta figurines with painted or engraved designs on their bodies dating back to 5000 B.C. These figurines were placed in tombs as religious or/and magical protection.

The first human testimonies on the use of tattooing in Japan date from the second and fourth centuries, and come from Chinese observers. Indeed, the Chinese were the first to speak about the practice of tattooing in the land of the rising sun.

In the second century, the history of the Wei kingdom mentions the tattooed face and body of certain Japanese, but Japanese texts do not mention the practice until the sixth century.

It appears that the Ainu people, the earliest inhabitants of Japan, used tattooing for decorative and social purposes during the Jōmon period (10,000 to 300 BC). Both men and women were tattooed:

- Men were tattooed to designate their membership in a particular clan or profession (especially sailors), and the tattoo was then supposed to protect from spirits;

- Women were marked by a tattoo covering the edges of the mouth and going up slightly on the cheeks in married women4. This last tradition continued until very recently, despite its prohibition in 1871.

These tattoos were frowned upon by Chinese chroniclers, as the act of tattooing was considered barbaric in their culture. There is no known link between these Ainu tattoos and the development of irezumi.

Buddhism spread little by little in Japan, and with it, the Chinese thought. At the beginning of the Kofun era (300-600 AD), tattoo designs started to have negative connotations.

Instead of being used for rituals or as representative of status, criminals began to be tattooed as punishment (a case similar to ancient Rome, where slaves who wanted to rebel were punished by tattooing phrases such as, "I am a slave who tried to escape his master."

This punishment replaced the amputation of the nose and ears that had previously been used. The criminal was marked with a circle around the arm for each offense, or with a character on his forehead.

Hand tattooing in the Nansei archipelago

In southern Japan, from the Amami Islands to the Ryūkyū Archipelago (Nansei Archipelago), women would get tattoos of designs on their hands, called hajichi. The tattoos sometimes went up to the elbows.

The earliest references to hajichi date back to the 16th century, although the practice is probably much older. It seems to have been associated with rites of passage: tattoos on the hands indicated that the woman was married. And when the tattoo was fully completed, the event was celebrated.

The condemnation of tattooing in the Edo period

During the Edo period (1600-1868), the Kojiki introduces a beginning of codification of tattooing. Indeed, it distinguishes the "prestigious" tattoo, reserved for heroes and great people, from the "villainous" tattoo, reserved for bandits and criminals4.

This change of image corresponds to the influx of population in the big cities like Edo and Osaka, which leads to the increase of delinquency.

The police generalized tattooing as a punishment, in order to deter potential criminals. But at the same time, other uses appeared in the population - patterns complementing each other when the hands of two lovers joined for example. It is during the Edo era that Japanese decorative tattooing started to evolve into the highly developed art we know today.

The most important development of this art took place with the birth of the woodblock printing technique and the publication of the popular Chinese novel Suikoden.

This book is a tale of rebellious courage and manly bravery lavishly illustrated with woodblock prints showing men in heroic scenes, their bodies decorated with dragons and other mythical beasts, flowers, fierce tigers, and religious images. The novel was an immediate success and the demand for the type of tattoos seen in its illustrations was simultaneous.

Artists using wooden blocks began to make tattoos. They used, for the most part, the same tools to print the designs in human flesh that they used to create their block prints, including chisels, gouges and, most importantly, a unique ink known as "Nara ink" or "Nara black", the famous ink that turns blue-green under the skin.

There is an academic debate about who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars argue that it was the working classes who wore, and displayed, such attributes. Others claim that wealthy merchants, prevented by law from displaying their wealth, wore expensive irezumi under their clothes. It is certain today that irezumi was very popular in certain trades:

- the prostitutes (yujo) of the pleasure districts, used the tattoos to increase their attraction for the customers;

- firemen were sometimes tattooed. Tattooing was then considered as a means of spiritual protection, in front of a dangerous job9 (and undoubtedly, for their beauty too);

- couriers (hikyaku) and construction workers, specialized in working at height (tobi), often worked wearing a simple fundoshi (loincloth). To avoid embarrassment, they covered their bodies with tattoos;

- the kyōkaku, a kind of "street knight", ancestor of the yakuzas. These outlaw heroes protected the weak and innocent from the powerful and corrupt elites.

A progressive rehabilitation in modern Japan

At the beginning of the Meiji era, the Japanese government, wanting to protect its image and to make a good impression on the West, declared tattoos outlawed and irezumi took on connotations of criminality. Nevertheless, fascinated foreigners came to Japan to learn the techniques of tattoo artists and the tattoo tradition continued in secret.

Tattooing was legalized in 1945 by the occupation forces but retained its image of criminality. For many years, traditional Japanese tattoos were associated with the yakuza, the notorious Japanese mafia, and many businesses in Japan (such as bathhouses, fitness clubs, and hot springs) still refused customers with tattoos.

Tattooing and other forms of body decoration and change, as in many countries in the Western world, is gaining popularity in Japan. Yet young Japanese who decide to get tattoos most often choose "single-spot" designs - small patterns that can be finished in one session - usually in American or tribal styles. More recently, however, tattoos using the Sanskrit siddham script are becoming more fashionable.

Traditional irezumi is still done by professional tattoo artists, but is painful, time-consuming, and expensive. A typical, traditional tattoo covering the entire body (arms, back, upper legs, and chest but leaving an untattooed space below the center of the body) can take one to five years, with weekly visits, and can cost up to $30,000.

The realization

Despite some changes in the process, including the sterilization of tools, or the use of an electric tattoo machine to complete some of the lines of their tattoos, the basic rituals, methods and designs of irezumi have remained unchanged for centuries. It is a very closed environment, preserving the tradition and preservation of irezumi as an art form, just like ikebana (flower arrangement) or chanoyu (tea ceremony) ritual. In order to get an irezumi tattoo, one must go through several steps.

The tattoo artist

The person who wants to get a tattoo must first find a traditional tattoo artist. This search can be a daunting task (although it has been made easier with the advent of the web). These artists are often surprisingly secretive and introductions are frequently made by word of mouth only.

A traditional tattoo artist trains for several years with a master. He (as they are almost exclusively men) will sometimes live in his master's house. He may spend years cleaning the studio, observing, practicing on his own flesh, making needles and other required instruments, mixing inks and meticulously copying designs from his master's portfolio, before he is allowed to tattoo clients.

He must master all the complex techniques required to meet the demands of his future clients. In most cases, his master will give him a tattoo artist's name, usually including the word "hori" (to engrave) and a syllable from the master's own name or another significant word. In a few cases, the apprentice will take the master's name.

Pattern and contour definition

After an initial consultation during which the client will tell the tattoo artist the design he or she wants (again, clients are mostly men, although women also wear irezumi, they are very often the wives or girlfriends of the tattoo artists), the work begins with the tattooing of the outlines.

Usually this will be done in one sitting, often freehand (without the use of a stencil), which can take several hours of work before it is finalized. When the outline is complete, shading and coloring is done in weekly sessions, whenever the client has money to spend. When the tattoo is finished, the artist will "sign" his work.

Tattooed people frequently keep their marks secret, as tattoos are still considered a sign of criminality in Japan, especially by senior citizens, and in the workplace. Ironically, many yakuza and criminals themselves avoid getting tattoos for this reason.

Irezumi Tattoo Glossary of Japanese terms

- Bokukei, bokkei (墨刑?): punishment by tattoo.

- Gobu (五分?): tattoo covering 5/10ths of the arm to the shoulder.

- Hanebori (羽彫り?, literally: cutting with a feather): a hand tattooing technique employing a feather movement.

- Hikae: tattoo encompassing the chest.

- Horimono (彫り物, 彫物?, literally: to engrave, to cut): tattoo. This is another word for traditional Japanese tattoos.

- Horishi (彫り師, 彫物師?): a tattoo artist.

- Irebokuro (入れ黒子?): from ire or ireru meaning "insert" and bokuro or hokuro, "mole".

- Irezumi (入れ墨, 入墨, 文身?), also pronounced bunshin (剳青, 黥 or 刺青?): tattooing/tattooing.

- Kakushibori (隠し彫り?, literally: hidden cut): tattooing near the armpits, inner thighs and other "hidden" parts of the body. Also refers to tattooing hidden words, for example among flower petals.

- Kebori (毛彫り?): the tattooing of fine lines or hair on tattooed faces.

- Nagasode (長袖?): tattooing from the arm to the wrist.

- Shakki: the sound the needles make when they prick the skin.

- Shichibu (七分?): tattoo covering 7/10ths of the arm to the forearm.

- Sujibori (筋彫り?): outline, tattoo outline.

- Sumi (墨?): the ink used to tattoo, traditionally prepared by the apprentice.

- Tebori (手彫り?, literally: cutting by hand): describes the techniques of tattooing by hand.

- Tsuki-bori (突き彫り?): a hand tattooing technique with a quick movement.

- Yobori: "yo" (European) tattooing. The Japanese-English term coming from the slang for the tattooing technique done by machine.

Symbolism of Irezumi Tattoo

Images are recurrently present in traditional Japanese tattoos, and have a particular meaning. Often they present qualities or defects, either innate or desired.

A parallel can be drawn with Western iconography, where the eagle, a popular tattoo figure, symbolizes bravery or nobility, or the heart, a symbol of loyalty and honesty. In Japan, irezumi are limited to representations of fauna or flora, religious motifs, heroes and folk figures.

- Flora:

- peony: symbolizes wealth and good fortune;

- the chrysanthemum : firmness and determination;

- the cherry blossom : symbolizes the ephemeral nature of life;

- the lotus.

- Animal drawings:

- the komainu (similar to the Chinese lion): symbolizes protection;

- the tiger : one of the heroes of Suikoden has a tiger tattooed on his back;

- the carp (in general, one swimming upstream and one downstream): courage;

- the snake.

- Mythological beasts:

- dragons;

- qilin ;

- baku;

- hō-ō (鳳凰, phoenix)

- Religion and literature :

- characters from traditional folklore and literature such as Suikoden ;

- images inspired by ukiyo-e prints: geisha, samurai ;

- Buddhas and Buddhist deities such as Fudō Myō-ō and Kannon;

- Shinto kami (deity) such as the tengu.

- Background: clouds, waves, wind symbolism.