Miyamoto Musashi

Share

Miyamoto Musashi is a traditional Japanese name; the family name (or school name), Miyamoto, precedes the first name (or artist name).

Miyamoto Musashi (宮本 武蔵), whose real name was Shinmen Bennosuke (新免 辨助?) was born on March 12, 1584 in Ōhara-chō in Mimasaka province and died on May 19, 16451. He is one of the iconic figures of Japan, a master bushi, calligrapher, renowned painter, philosopher and the most famous fencer in the country's history.

His full name was Shinmen Musashi-no-Kami Fujiwara no Harunobu (新免武蔵守藤原玄信?), Musashi-no-kami was an honorary (and obsolete) title dispensed by the imperial court making him the governor of Musashi province (in the area of present-day Tokyo).

Fujiwara is the name of the aristocratic lineage to which he belongs. Harunobu was a ceremonial name, similar to a compound name for a sinicized gentleman, notably used by all high ranking samurai and nobles.

Adept of kenjutsu

Miyamoto Musashi's grandfather was a very good fencer related to the Akamatsu clan by his lord Shinmen Iga-no-kami who as a reward allowed him to bear his family name.

That is why Musashi signed the Book of Five Rings (Go rin no sho) with the name of Shinmen Musashi. Musashi's father was known as Muni. Today, he is also known as Munisai, a fictitious name which is a creation of the writer Eiji Yoshikawa.

For reasons that are unclear, perhaps because of the jealousy he had aroused around him, Munisai withdrew from the entourage of Lord Shinmen and retired to the nearby village of Miyamoto-mura.

It seems that Musashi was born there and this is the origin of the nickname given to him: Miyamoto Musashi. However, at the very beginning of the Scroll of the Land, in the Go rin no sho, Musashi writes: "I was born in Harima prefecture" (part of present-day Hyōgo). His place of birth is therefore subject to controversy.

His father died when he was 7 years old. Japanese researchers suggest that it was his stepfather. According to a legend, Miyamoto Musashi laughed at his father, a fencer, and ended up making him impatient. That day, Munisai was busy cutting a toothpick and, fed up with his son's mockery, he lost his temper and threw his knife at his son who dodged the weapon with his head.

Even more furious, Munisai would have thrown the blade again. But Musashi was able to avoid it again. His father was furious and chased him out of his home, forcing the boy to spend his childhood under the care of his uncle, a monk and monastery owner.

He fought in duels and killed for the first time at the age of 13 (against Arima Kihei in 1596). At the age of 16, he participated in the battle of Sekigahara (1600) which saw the victory of Tokugawa Ieyasu's army following the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Engaged in the losing side, he was left for dead on the battlefield but survived his wounds. Until the age of 29, he participated in about 60 duels, most of them with a wooden sword (bokken) while his opponents had real swords (nihonto).

He single-handedly challenged and annihilated the entire Yoshioka school of fencing, fighting 60 or more fighters (some sources mention that he killed 79 disciples of the Yoshioka style in the skirmish at the foot of the Parasol Pine at Kyoto's Ichijō-ji temple). It was there that he practiced for the first time - without being aware of it - his famous two-sword technique which he later developed.

His last (and most famous) duel took place on April 13, 1612 against the other greatest fencer in Japan, Sasaki Kojirō, whom he defeated on the island of Funa, probably with a long bokken, which was cut from an oar of the boat that brought him there, but the various accounts of this battle are not very sure. No reliable source gives Sasaki's name.

It is possible that he was called Kojirō Ganryū instead. Musashi went to the Hosokawa family and in particular to the daimyo Hosokawa Tadatoshi, a loyal family related to that of the Tokugawa shogunate. He entered only as a guest, which would explain the relatively modest pay he received for his services. He then stopped dueling.

In no text written by Musashi does he directly mention his opponents, except for Arima Kihei, the first one. He does not name Sasaki Kojirō or Shishido Baiken, nor the Yoshioka family, yet many of them have remained famous, integrated into his legend.

In one of his fights, Musashi confronts Nagatsune Hachiemon, a master spearman in the service of Tokugawa Yoshinao, from Owari province. After a conversation, they decide that a duel would be useless and, instead, Nagatsune invites him to play a game of go against his son, which Musashi accepts.

During the game, Nagatsune's son proves to be very talented and they are soon absorbed in the game, when suddenly Musashi cries out, "Don't even try!" Indeed, Nagatsune had sneaked quietly into an adjacent room and was about to stab his guest with his spear.

Having broken the momentum of his opponent, Musashi returned to the game without moving or saying anything else, much to the perplexity of his two opponents. Nagatsune having sensed that Musashi's skills were superior to his own silently admitted defeat and Musashi also won the go game.

It is also known that Musashi was gifted with extraordinary physical strength, necessary to slice through bones when using a sword with one hand. In a passage from the Nitenki, Lord Nagaoka asks Musashi to help him choose bamboo to make flagpoles.

At his request, the lord brings him all the available bamboos, about a hundred in total. Musashi throws them and makes a quick attack in the air: all the bamboos break except one, which he hands to Lord Nagaoka. Lord Nagaoka told him that this was an excellent way to test them, but that only Musashi could do it.

Afterwards, he was put in charge of an army corps of Lord Ogasawara and participated in the siege of Hara castle in 1638, during the revolt of the Christians, led by Amakusa Shirō.

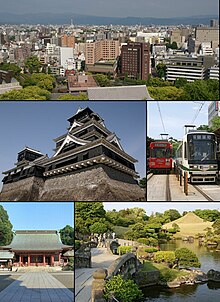

After returning to Kumamoto, he devoted himself mainly to artistic activities, but it is known that he kept a sharp mind and certain physical abilities. For example, as an old man, Musashi was trapped on a roof during a fire; he used a beam or ladder to run lightly over it, making his way to another house.

Musashi had two adopted sons Miyamoto Mikinosuke and Miyamoto Iori. Miyamoto Musashi educated Mikinosuke and introduced him to Honda Nakatsukasa Taiyu (Honda Tadaoki), lord of Himeji castle in Banshu. Returning to Edo, Miyamoto Mikinosuke died in 1626 at the age of twenty by seppuku in the third year of the Kanei Era to follow his lord.

Minamoto Iori met the master in 1624 and was later employed by Ogasawara Tadazane. He was then promoted to the title of superior vassal of Ogasawara. He died in 1678. And Takemura Yoemon is said to have left evidence as a disciple.

Terao Magonojō, older brother of Terao Motomenosuke, a favorite student of Miyamoto Musashi who was entrusted with the Book of Five Rings (Go rin no sho), worked alongside Musashi and often trained with the kodachi, a type of short sword that broke under the master's bokken. Magonojo burned the original Go rin no sho on Musashi's orders, so the original version cannot be found9.

At the age of 59, in 1643, Shinmen Musashi-no-kami moved to Mount Iwato, located near Kumamoto, where he settled in the Reigandō ("Cave of the Spirit-Rock"). There he set up a low table and began, on the tenth day of the tenth month, to write the Book of Five Rings.

Miyamoto Musashi Last days

In the early spring of 1645, Musashi put his pain-ridden body to the test and began the arduous climb up the path to Reigandō Cave (霊巌洞, meaning "spirit of the cave"). In April of the same year, aware of his impending death, he wrote a courteous missive to the senior vassals of the Hosokawa clan:

"In my analysis of the Laws of the Two Swords, I have not supported my exposition with maxims and principles borrowed from Confucianism or Buddhism; nor have I repeated the hackneyed anecdotes that are all too familiar to practitioners of the military arts.

I have meditated at length on all the artistic paths and achievements. Consider this effort as a will to conform to the principles of the universe; and today, I really regret not having been better understood.

When I criticize my life's journey today, I am tempted to blame myself for an excessive investment in the warrior arts; this is certainly attributable to my martial syndrome. I have sought fame and it seems to me that I am leaving a notorious name to this unstable world.

Today, however, my arms and legs are worn out and I cannot but resolve, under the weight of the years, to stop teaching my school myself. Also, it seems to me, in these conditions, very difficult to envisage any project; I only wish to isolate myself from society and to retire in the mountains while waiting serenely for death, even if only for one day. I am grateful to you for seeing in these words the expression of my request.

- April 13, 1645. Miyamoto Musashi

Shortly after sending this letter to the addressees, Musashi undertook the final and arduous ascent of Mount Iwato, heading for the Reigandō cave where, isolated from the commerce of men, he serenely awaited death.

Watching over the old master

The man in charge of looking after Musashi's welfare during his last years of life was Matsui Nagaoka Sado no Kami Okinaga. Considering that Okinaga had once been a student of Musashi's father, it is not surprising that this vassal, and Yoriyuki, his adopted son, were entrusted with the care of the old warrior.

On a beautiful spring day, at the beginning of May, Yoriyuki, pretending to go on a hawk hunting trip, climbed the mountains, made a detour to the cave and "convinced" him to return with him. The old man had always made a point of fighting for his independence and now he was forced to go back down to the valley.

At this time of the year, the sun is scorching over Kyūshū, but Yoriyuki did not fail in his duty and Musashi was soon able to lie on his futon, on the floor in his residence in the old castle of Chiba, being cared for, under the benevolence of his disciples Terao Kumanosuke and Nakanishi Magonosuke.

Final instructions

On May 12, he called his students to give them his final instructions. He began by giving his swords as souvenirs to Okinaga Yoriyuki and his favorite student, Terao Katsunobu, he gave the work he had just finished, "The Book of the Five Rings", and to his brother Terao Kumanosuke, he entrusted "The Thirty-Five Articles of Martial Arts".

After dividing his possessions among his students, he put his personal belongings in order, took up a brush for the last time and wrote a small manuscript in one go. He entitled it "The Way of the Solitary" - or "The Way of Independence. The twenty-one maxims that make up this work are really a summary of his life experience, biographically and spiritually.

Musashi died on May 19, 16451, in his residence in the Chiba Castle compound. He was in his sixty-second year. In accordance with his last wishes, his body was dressed in armor and helmet, equipped with the six military accoutrements and was buried in Handagun, Tenaga Yuge village.

The priest Katsukawa Shunzan officiated at the occasion in Taihō-ji temple, and his tombstone is still in place today. It was not long before others close to the deceased warrior also passed away. By December of that year Hosokawa Tadaoki and Takuan Sōhō had passed away.

Miyamoto Musashi Legacy and continuity

The secrets of how to handle the sword were not the prerogative of a few privileged students (Ishikawa Chikara, Aoki Jœmon, Takemura Yœmon, Matsui Munesato and Furuhashi Sozaemon). All of them were excellent swordsmen.

Thus, while The Book of Five Wheels and The Thirty-Five Articles of the Martial Arts were given as gifts to the Terao brothers, what he really passed on to each of his students was his own spiritual determination to clarify the cryptic issue of life and death.

With such a spiritual legacy as this, the master's teaching could not have resulted in the emergence of a true school with its own rules, certificates and diplomas. Musashi could teach his techniques, give advice, but ultimately it was up to the student to measure his own strength, to evaluate his Way, and to make it his own.

Thus, the Musashi style is still taught today, but the true content of Niten Ichi-ryu disappeared along with its founder. How could it be otherwise? When he was teaching in Owari, Yagyū Hyōgonosuke pointed this out, who declared:

"Musashi's sword belongs to him alone and no one else could wield it so effectively".

Mutation

In the Japan of Musashi's time, a major mutation affected the armament. During the second half of the sixteenth century, wick muskets , recently introduced by the Portuguese, had become the decisive weapons on the battlefield; but in a country at peace the samurai were able to turn their backs on the firearms they disliked, and renew their traditional idyll with the sword (nihonto (日本刀, "Japanese sword").

Fencing schools flourished (Budō, The budō (武道). However, as the possibility of using the sword in actual combat diminished, martial skills gradually became martial arts, which increasingly emphasized the importance of inner self-control and the qualities of fencing for character building, rather than military effectiveness. A whole mystique of the sword developed, more related to philosophy than to war.

Fluidity

In the strategy of attacking without attacking, Musashi talks about how, with an imperceptible movement, one moves from one position to another in a smooth and fluid manner:

"you must adopt an attitude that allows you to move to another mode of combat without having to make a conscious decision. You must be available and not favor one particular technique over another. A warrior has only one objective - to destroy the enemy by whatever means.

Fluidity implies the total absence of hindrances, especially at the level of the mind. Not to create the chains that will constrain our mind, not to make it rigid. In the Book of the Wind, the author evokes this principle:

"Knowledge of sword attack techniques [...] is undesirable in the martial arts. Thinking about the various ways to slay the opponent confuses the mind.

It is detrimental to specialize in certain guards. Creating immutable truths in a hurry has nothing to do with the Way of Victory.

By fixing the mind on a specific place, they confuse it and contaminate the martial art."

An anecdote about Musashi and Takuan Sōhō16 (a prelate of the Rinzai sect, close to the bushi, founded on the 28th patriarch Bodhidharma or Daruma) illustrates these words. While they were discussing the virtues of Zen and its applications in daily life, the priest suggested that the swordsman attack him with a wooden sword. Takuan would defend himself with his fan alone.

It is reported that Musashi, while on guard, found himself very embarrassed in front of Takuan and did not manage, despite his changes of guard, to find a way out. Takuan, for his part, stood there, motionless, fan in hand, arms relaxed.

After a while, Musashi finally threw down his weapon in disgust and declared that he had not found the opening to infiltrate. Takuan's mind was everywhere and therefore nowhere; and in this state of perfect fluidity, he had become unassailable.

Without a doubt, Musashi meditated at length on this "confrontation. It was on the strength of this experience that he wrote:

"Without fixing your mind anywhere, strike the enemy quickly and decisively."

This gives us a different perspective on the line from Kamo no Chōmei - "If the flow of the river is infinite, the water that flows is in perpetual motion" - a reading certainly prized by the old anchorite.

"The Way of victory is to work out the difficulties of your enemy."

By the time he was thirty years old, Musashi had already won sixty singular duels and, by his own admission, this feat was not due to physical strength, superior speed or unusual gifts.

Wandering on the roads of Japan, one can think that he thought long and hard about the mindset of his opponents and - let's not forget - about his own. It is this capacity for introspection, combined with a natural curiosity and a constant search for the essential that distinguished him from his contemporaries. This is the reason why his concise work is so successful today.

In addition to these principles, he also spoke at length about the importance of taking the initiative in combat, the importance of really experiencing each of the weapons at the warrior's disposal, of perceiving the different rhythms, of having both a global and a precise point of view, and, above all, of reading the opponent's mind with an open book without letting him read yours.

Musashi believed in a sum of principles, not a combination of tricks and other devices, and he valued substance and essence over form and presentation. The principles that his experience allowed him to discover appear in The Book of Five Rings, whether explicitly or implicitly.

To understand the content of the book, read it carefully, through the filter of our own experience. Doesn't the author write:

"A simple reading of this book will not allow you to reach the essence of martial arts. As you skim the lines, consider that the content is specifically addressed to you and do not be satisfied with a simple skimming.

Soak up their teaching and do not try to imitate it. Consider the principles as your own, as if they were the fruit of your own reflection, and constantly strive to experience them on a physical level."

Japan closes its doors to the outside world

Toyotomi Hideyoshi succeeded Oda Nobunaga who was assassinated in 1582. Concerned about a possible colonization of Japan and the revolt and conversion of several lords, he issued a decree banning Christianity on July 24, 1587.

Missionaries were forbidden to stay in Japan and only trading ships from Christian countries were allowed to enter. The massacres were considerable and lasted for several decades. Japan closed its doors to the outside world, favoring two hundred and fifty years of peace.

Miyamoto Musashi, born in 1584 in Ōhara-Cho in the province of Mimasaka is entrusted with the command of an army corps of Lord Ogasawara, and participates in the siege of Hara Castle in 1638 against the revolt of Christians led by Shirō Amakusa.

Finally he returned to Kumamoto and devoted himself mainly to artistic activities as a guest of the patron Hosokawa Tadatoshi , third lord of Kumamoto and descendant of Hosokawa Gracia, a prominent figure who had converted to Christianity. He left a work that is now a Japanese national treasure.

Miyamoto Musashi as Artist

His fame allowed him to discover, as a spectator, other arts in which he showed a certain interest. This was the case for Chinese ink painting, sculpture and garden art. It was during this period that he met the famous artist Kaihō Yūshō.

He was a renowned calligrapher and painter whose sumi-e productions can still be admired. His paintings were inspired by Liang Kai and the Kanō school, which was in vogue at the time. One of his best-known works is his depiction of Daruma, the founder of Zen, which was reportedly praised by Lord Hosokawa as a pure masterpiece.

He designed a garden in Kumamoto, which was destroyed during World War II.

Musashi, would follow in the tradition of the great traveling artists of the Japanese archipelago - Saigyō Hōshi, Enkū, Matsuo Bashō and Hiroshige, among many others - and his source of artistic inspiration from the heart of nature itself.

Painting with the spirit of the sword

It is not known exactly when Musashi began to wield the brush, although at the early age of thirteen he executed a portrait of Daruma (達磨) at the Shōren-in temple in Harima province, the place where he took up residence following his departure from his father's home.

It is assured, however, that by the time he entered Kokura in northern Kyūshū in 1634, he was gifted with unusual talents. All the paintings that have come down to us through the centuries are indeed between that year of 1634 and the master's death in 1645.

According to Zen Buddhist painters, in suibokuga, the brushstroke reveals the temperament that animates the artist and the spirit is spontaneously embodied in the utensil. Convinced that the Way of the sword was a sesame to the other artistic Ways, Musashi maintained that fundamentally, the brushstroke and the sword stroke were identical: can we not, in both cases, read the artist's mind openly?

Urban planning and gardens

His work as urban planner of the walled city of Akashi, for the Ogasawara in the areas of defensive strategy and garden art earned him a certain notoriety, which is why, a few years later, the Honda Clan, installed a few kilometers away, in Himeji, offered in turn the services of the artist.

Without relaxing the efforts he devoted to the maturation of his own style, he worked in Himeji on the town planning of the walled city and designed the gardens of some of its temples. Both the Ogasawara and Honda clans respected Musashi deeply and valued his services.

As he approached 40 years of age, it seems that the time he shared between the new walled cities of Akashi and Himeji could be counted in years. One can imagine that his fame and prestige were considerable. In these conditions, he was certainly able to preserve his freedom by maintaining the status of "guest" rather than by assuming that of "samurai ".

Works

In search of live models, the artist could go to the banks of the river that still flows east of Kumamoto Castle. At the time, the river was a natural expanse; geese, ducks, and other birds flourished there in great numbers.

These and many other paintings by the master are now housed within the walls of the Eisei Bunko Museum, which serves as a repository for the treasures amassed by the Hosokawa clan since the fourteenth century.

Miyamoto Musashi as Author

He is the author of several texts on the sword and its strategy:

- Hyodokyo, The Mirror of the Way of Strategy;

- Hyoho Sanjugo Kajo, Thirty-five instructions on strategy;

- Hyoho Shijuni Kajo, Forty-two Instructions on Strategy;

- Dokkōdō, The Way to Go Alone;

- Go rin no sho, The Treatise of the Five Wheels.

These texts are primarily study manuals employed in his sword school. Many martial arts were inspired by his works.

Go rin no sho

He is the author of a strategy book, Go rin no sho , written at the age of 60, translated into French as Livre des cinq anneaux or Traité des cinq roues. The title is read in Japanese as Gorin sho, but the translators have adopted the current Japanese reading of Gorin no sho.

Towards the end of his life, he meditated and introspected on his past and his experience; he deduced that the principles he had implemented in his martial art (duels) could also be implemented not only in military strategy (mass confrontation) but in all fields.

The "five rings" or "five circles" refer to the five tiers of Buddhist funerary monuments (gorintō) that represent the five elements of Japanese tradition. The book thus has five chapters:

- Earth : Musashi explains here the main lines of his tactics and to make his explanations more accessible he compares it to the carpenter's trade.

- Water : Musashi explains a method to forge oneself physically or spiritually. He explains how to keep one's mind alert, how to maintain one's body and eyes, how to hold and use a sword, the position of the feet, etc. Everything he writes is based on his own experience, acquired throughout his life by dint of fighting and exercises carried out relentlessly for many years. What he writes is not a figment of his imagination; everyone can benefit from it for themselves no matter what kind of life they lead.

- Fire: Musashi explains the tactics to be applied in the simple duel and in the great battles, he thinks that the same rules govern them.

- Wind : criticizing the characteristics of other schools, Musashi emphasizes the philosophical spirit of his Niten school.

- Emptiness: a statement of the bushi's ideal; the notion of emptiness as a goal to be achieved is a recurring theme in budō and the culmination of Musashi's tactics can be summarized in one word: Emptiness. Emptiness is comparable to the firmament purified of all clouds of misguidance. The Japanese ideogram reads kū in the Chinese way, and sora in the Japanese way. Sora rather refers to the sky, and kū refers to the Chinese and Buddhist notion of "emptiness". Translating it as "emptiness" is consistent with the Buddhist aspect of the path described by Musashi.

Dokkōdō

At age 60, Musashi wrote his testament of sorts through the Treatise of the Five Wheels. Two years later, feeling his end approaching, he wrote the Dokkōdō (The Way to be Followed Alone):

- Do not contravene the unchanging Way of Men.

- Do not seek the pleasures of the body.

- Be impartial in everything.

- To think of oneself lightly, to think the world deeply.

- Throughout life, keep away from lust.

- Have no regrets.

- Do not envy others for good or bad.

- Not to be saddened by any separations.

- Do not let oneself go to complaints or grudges towards others or oneself.

- Not to be guided by the desire for love.

- To have no preference in all things.

- Do not seek comfort.

- Not to seek the finest delicacies in order to satisfy one's body.

- Not to surround ourselves with objects in order to use them in the distant future.

- Not to let false beliefs guide our actions.

- Never be tempted by any object other than weapons that are useful.

- To go forward without fear of the death that stands in the way.

- Not to seek riches for old age.

- To revere the Buddhas, but not to rely on them.

- To give up one's body but not one's honor

- Never abandon the Way of tactics.

Miyamoto Musashi as Educator

He founded the Niten Ichi Ryu school, whose main branch is the Hyoho Niten Ichi Ryu. Hyōhō Niten Ichi Ryu is translated as "the School of the Strategy of Two Skies as One Earth". Today, a lineage of masters descends directly from Musashi's disciples.

This sword school, a koryu of kenjutsu, was first called the "School of Two Swords" (Niken Ryu), then the "School of Two Heavens" (Niten Ryu). It remains renowned for its unusual style: simultaneous use of two swords, one short, the other long. The hyōhō, from Hyōhō Niten Ichi Ryu, means "strategy" and is a key teaching in the school.

There are also several schools around the world with the suffix Niten Ichiryu, but they do not officially have any sort of heritage link to Hyoho Niten Ichiryu. Some schools are authentically descended from Miyazawa. Some schools are authentically descended from Miyamoto Musashi without being the "mother" branch and are considered as koryus.

They transmit their teachings with the permission of the soke and must expressly demonstrate their lineage of transmission and the formal agreement to teach from the soke of that branch. Any inaccuracy or withholding of such information is indicative of improper teaching in its reference to the Musashi school.

The Musashi school transmits its experience through its technique and spirit. To transmit only the technique is a serious amputation of the founder's teaching which distorts the deep meaning of a koryu: "In Hyoho Niten Ichi Ryu, the successor must dedicate himself to training and prove to his contemporaries, by his example, that the founder's teaching and kokoro are absolute and authentic. This is my mission as a soke.

Thus, the soke alone is able to explore the many meanings of this teaching because he alone possesses the transmission of the spirit that authenticates the gesture.

The student's goal is then to approach Musashi's experience with the guarantee that the knowledge inherited from the soke offers. For this reason, every teacher of the Hyoho Niten ichi Ryu or of any authentic branch of the Niten Ichi Ryu must cultivate a learning relationship with the grandmaster of his branch.

His motto

Seishin chokudo: "Sincere heart, Right Way (誠実な心、正しい方法) ".

Principles

Musashi's teaching can be reduced to nine principles:

- Avoid all perverse thoughts.

- To forge oneself in the Way by practicing oneself.

- To embrace all the arts, not just one.

- To know the Way of each profession, and not to limit oneself to the one one one practices.

- To know how to distinguish the advantages and disadvantages of each thing.

- In all things, get used to intuitive judgment.

- To know instinctively what one does not see.

- Pay attention to the smallest detail.

- Do not do anything unnecessary.

The principles are to be studied, the bokken in hand, with a master. The special feature of the koryūs teaching is that the sōke is expected to embody and prove his mastery with each generation.

Techniques

Miyamoto Musashi created a series of seiho, commonly called katas:

- Tachi seiho: 12 seiho with the dachi, long sword. However, the study is done with the bokken.

- Nito seiho: 5 seiho with the dachi and the kodachi, long and short swords, which correspond to the 5 seiho of the Book of Water. The study is done with the bokken.

- Kodachi seiho: 7 techniques with the kodachi.

- Bōjutsu: 20 seiho with the bō, long stick.

Weapons

Musashi designed a pair of bokken with a lighter weight and thinner profile33. All of the school's sword seiho are performed with the bokken and not the katana. Musashi's favorite bokken still exists today, a magnificent object made of dark wood, with a hole in the handle for a purple silk tassel; it is nicknamed Jissō Enman no Bokutō, after the inscription on the omote side.

Long passed down from soke to soke, it represents the desire to preserve the Niten Ichi Ryu style as is, without modifications or adaptations. Designated a National Treasure, it now sits as a relic at the prestigious Usa-jingū Shrine for its preservation.

Of course, Musashi also personally wielded steel weapons. One of his acquaintances was the famous blacksmith Izumi-no-kami Kaneshige, who was the teacher of Kotetsu, another renowned artisan.

The katana nicknamed Musashi Masamune is sometimes associated with him, although this is uncertain (Musashi's name could have come from somewhere else, and the Masamunes were fiercely jealous of the Tokugawa clan).

It is also known that at one point in his life, Musashi wore a daishō forged by Nagakuni, it is inscribed on their nakago (silks) "Shinmen Musashi-no-kami used this". The daitō appears to be in a museum, while the shōtō is privately owned by a Japanese collector named Suzuki Katei. Their authenticity is admitted and Musashi really was the owner.

Musashi in Japanese and world culture

When he died on May 19, 1645, the stories of his exploits had gone through some forty years of peddling and embellishment; and, as the Tokugawa government established its political and cultural power, and as Japanese society as a whole moved towards ever greater conformity,

the fame of a man who had certainly become the greatest swordsman of his time without claiming any inheritance or teaching, and without sacrificing his freedom on the altar of social recognition, could not but swell. Equally important in the genesis and maturation of the myth was the growing interest in leisure and recreation at that time.

"Aspire to be like Mount Fuji with a base so broad and solid that the strongest of earthquakes cannot shake you, and so great that the greatest of ordinary men's undertakings will seem insignificant from your highest perspective. If your mind can rise as high as Mount Fuji you will see all things very clearly. You will be able to perceive all the forces that set events in motion, not just those that preside over what is happening near you."

- Miyamoto Musashi.

Budokan Miyamoto Musashi

On May 20, 2000, at the initiative of Tadashi Chihara sensei the Miyamoto Musashi Budokan was inaugurated the day after Miyamoto Musashi's birthday (March 12, 1584, Ōhara-Chō - May 19, 1645)36. It is built in Ōhara-Cho in the province of Mimasaka the birthplace of the samurai.

Inside the building the life and journey of Miyamoto Musashi are recalled everywhere. Dedicated to martial arts, the Budokan gathers all the official traditional schools of sword and kendo in Japan. Practically, historically and culturally it is a junction for martial arts disciplines in the heart of traditional Japan dedicated to Musashi.

Legend and popularity

The combination of the Tokugawa Pax - characterized by pervasive government control over the various strata of social life - and relative economic prosperity - especially among the merchant class - led to a certain amount of excitement and an increased demand for entertainment.

Public entertainment took on new forms, and even though Japan already had a plethora of heroes who could be used as alibis for a plot, the need for novelty was still felt.

The burgeoning legend of Musashi was timely. Less than a century after his death, his biography - sometimes overly embellished - was brought to the stage in kabuki and bunraku, peddled by professional storytellers. His character was also recurrent on the newest woodcuts produced for an audience of insiders. In these artistic genres, his popularity continued for over two centuries.

Modern times and new media have only accentuated this already growing popularity. Beginning with Eiji Yoshikawa's best-selling Musashi (宮本武蔵), the swordsman, artist and writer that he was, was placed at the heart of countless storylines: novels, movies, series, TV programs and games, and even a multi-volume comic book.

The very foundation of the man was too good not to be embellished anyway; so much so that everyone seemed to want to monopolize his character.

Thus, over the decades and with the technological evolution of the means of communication, the Japanese public - joined by the Western world - did not want to let such a legend die out.

Paintings and prints

Under the Tokugawa shogunate, an era of peace and prosperity resulted in the emergence of an urban and merchant bourgeoisie. This social and economic evolution was accompanied by a change in artistic forms, with the birth of ukiyo-e and printmaking techniques allowing for inexpensive reproduction on paper, a far cry from paintings such as those of the aristocratic Kanō.

Miyamoto Musashi inspired Japanese painters including Utagawa Kuniyoshi, a great master of ukiyo-e.

Noh theater

Noh has evolved in various ways in popular and aristocratic art. It will also form the basis of other dramatic forms such as kabuki. After Zeami set the rules of Noh, the repertoire became fixed towards the end of the 16th century and still remains intact to us.

Master Kano Tanshū, a Noh actor of the Kita school, created a play dedicated to Musashi, Gorin-sho-den, in Aix-en-Provence in 2002. In September 2008, he performed Miyamoto Musashi's Gorin no sho outdoors by the river in Kokura (Fukuoka), the place where this samurai lived.

Books

- Musashi written by Eiji Yoshikawa, translated into French in two volumes: La Pierre et le Sabre and La Parfaite Lumière, J'ai lu, coll. "Littérature", vol. 1, 856 p. (ISBN 978-2290300541), vol. 2, 695 p. (ISBN 978-2290307830). These two books are not biographies, but novels; if some historical facts and features are preserved, most of them are invented.

- Vagabond, a manga by Takehiko Inoue, adapted from Musashi.

- The manga Usagi Yojimbo also refers to Musashi Miyamoto: Stan Sakai tells the adventures of a samurai named Miyamoto Usagi (usagi means "hare" in Japanese) who became rōnin after the battle of Adachigahara.

- Shôtarô Ishinomori, Miyamoto Musashi: One Shot Sensei (manga), Éditions Kana, coll. " Sensei ", 2008, 496 p. (ISBN 978-2505004141).

- Gen Takekura (Musashi), an American soccer player from Eyeshield 21 owes his nickname to Musashi Miyamoto.

- He appears in a story of the manga Dr. Slump Le Duel manqué de Kojirô.

- The Way of the Sword (2002), by Thomas Day, is based on the story of Miyamoto Musashi and involves him in a fantasy world.

- Taitei No Ken, vol. 4 (manga) by Yumemakura Baku (scenario), Dohe (drawings), published by Glénat, July 21, 2010. Miyamoto Musashi appears as the legendary warrior, the finest blade in Japan.

- In Soul Eater, the character of Mifune is named after Toshirō Mifune, Miyamoto Musashi's interpreter in Hiroshi Inagaki's The Legend of Musashi.

- In Chris Bradford's Young Samurai (en) trilogy, the character of Masamoto Takeshi, creator of the Niten Ichi Ryu, a great samurai using the "two-sky technique," is a fictional use of Musashi Miyamoto. He adopts Jack Fletcher and makes him a samurai apprentice.

- In The Secrets of the Immortal Nicolas Flamel (especially in The Enchantress), Miyamoto Musashi (called Niten) plays a fairly important role.

- William Scott and Alex Fébo (Translation), Musashi, le samouraï solitaire : La vie et l'oeuvre de Miyamoto Musashi, Budo Editions, coll. " Arts martiaux : biographie ", 2009, 319 p. (ISBN 978-2-84617-103-8).

- David Kirk, Le Samouraï, Le Livre de Poche, coll. " Littérature ", 2015, 504 p. (ISBN 978-2-253-01727-1), tells the story of Musashi Miyamoto's youth up to the battle of Sekigahara.

- David Kirk and Marina Boraso (Translation) (trans. from English), L'Honneur du samouraï : roman, Paris, Albin Michel, 2018, 528 p. (ISBN 978-2-226-32073-5), the legendary warrior Musashi Miyamoto, author of the famous Treatise of the Five Wheels.

- Tadao Takemoto39, Miyamoto Musashi, warrior of Transcendence: towards a dialogue between bushidô and chivalry, Signatura, 2019, 144 p. (ISBN 978-2-915369-42-7).

- Tadao Takemoto and Olivier Germain-Thomas, L'Âme japonaise en miroir: Claudel, Malraux, Lévi-Strauss, Einstein..., Entrelacs, coll. "Hors collection", 2014, 250 p. (ISBN 978-2-908606-87-4)

Films

- 1943: With Two Swords (二刀流開眼, Nitōryū kaigen), directed by Daisuke Itō.

- 1944: The Story of Musashi Miyamoto (宮本武蔵, Miyamoto Musashi), directed by Kenji Mizoguchi.

- 1954: The Legend of Musashi (宮本武蔵, Miyamoto Musashi), directed by Hiroshi Inagaki.

- 1954: Miyamoto Musashi, directed by Yasuo Kohata.

- 1955: Duel at Ichijoji (続宮本武蔵 一乗寺の決闘, Zoku Miyamoto Musashi: Ichijōji no kettō), directed by Hiroshi Inagaki.

- 1956: The Way of Light (宮本武蔵完結編 決闘巌流島, Miyamoto Musashi kanketsuhen: Kettō Ganryūjima), directed by Hiroshi Inagaki.

- 1961: The Legend of Musashi Miyamoto (宮本武蔵, Miyamoto Musashi), directed by Tomu Uchida.

- 1962: The Lancers Monks of Hozoin Temple (宮本武蔵 般若坂の決斗, Miyamoto Musashi: Hannyazaka no kettō), directed by Tomu Uchida.

- 1963: Two Swords (宮本武蔵 二刀流開眼, Miyamoto Musashi: Nitōryū kaigen?), directed by Tomu Uchida.

- 1964: Alone Against All in Ichijoji (宮本武蔵 一乗寺の決斗, Miyamoto Musashi: Ichijōji no kettō), directed by Tomu Uchida.

- 1965: Dawn Duel (宮本武蔵 巌流島の決斗, Miyamoto Musashi: Ganryū-jima no kettō), directed by Tomu Uchida.

- 1971: Duel to the death (真剣勝負, Miyamoto Musashi: Shinken shobu), directed by Tomu Uchida.

- 1973: Miyamoto Musashi (宮本武蔵), directed by Tai Katō.

- 2003: Musashi (武蔵), TV movie directed for NHK, starring Ichikawa Ebizo Shinnosuke.

- 2014: Miyamoto Musashi (宮本武蔵), television mini-series

- 2020: Crazy Samurai Musashi, directed by Yūji Shimomura.

- In Akira Kurosawa's The Seven Samurai, the character of Kyuzo, played by actor Seiji Miyaguchi, is inspired by Miyamoto Musashi.

One of the two protagonists in the 2003 film Aragami, by Ryūhei Kitamura, claims to be Miyamoto Musashi.

Anime

- In the manga Fūma no Kojirō by Masami Kurumada, the character Musashi Asuka is inspired by Miyamoto Musashi.

- Shura no Toki (The Shura Era), Japanese anime made in 2004.

- In the episode The Trap Lament [2/2] of Samurai Champloo, a strange hermit hints that he might be Musashi.

- Miyamoto Musashi: Sōken ni Haseru Yume is an anime / historical documentary, about Musashi46.

- In the Pokémon anime series, a gang of thieves initially named Roketto Dan (Team Rocket) has three members, one of whom is named Musashi (she is called Jessie in the VF), and her mother's name is Miyamoto... Her friend, who is also part of the Roketto Dan is named Kojiro (he is called James in the VF). Musashi is a character known in Pokémon for her strong personality and, as in the story of Musashi Miyamoto, she likes to hit her sidekick Kojiro... She is also an expert in martial arts. The only notable difference between Musashi of the Roketto Dan and Musashi Miyamoto is that Musashi of Pokémon is very friendly with Kojiro... It cannot be said that the Musashi and Kojiro of the Pokémon series are those of the Japanese story, but it can be said with certainty that the creator of the Roketto Dan (Takeshi Shudô) drew on this story to invent these characters.

- In the manga Eyeshield 21, a kicker of the American soccer team Devils bats is called Musashi, he can score from very far and his main rival is called Kojiro of another team.

- In Inazuma Eleven GO, the warrior spirit, or Keshin of Ryoma, is called Musashi the Valiant Samurai (Sengoku Bushin Musashi in Japanese) and has two katanas.

Manga

- Shotaro Ishinomori, Miyamoto Musashi, Kana Publishing, coll. "Sensei", 2008, 486 p. (ISBN 978-2505004141).

- Yamatori Niten, Wandering Samurai, Clair de lune, coll. " Encre de Chine ", 2012, vol. 1 (ISBN 978-2353255023); vol. 2 (ISBN 978-2353255030).

- Takehiko Inoue's manga Vagabond is loosely based on the life of Musashi Miyamoto.

- In the manga Samurai Champloo (episode 21), he was drawn as a half-mad old fisherman who saves one of the characters (Jin) and teaches him to fish.

- Miyamoto Musashi appears notably in the manga Amakusa 1637 by Michiyo Akaishi.

- Miyamoto Musashi is also a secondary character that Azumi encounters in Yū Koyama's eponymous manga. He is identified as such in chapter 172.

- In the manga Baki Dō (バキ道) by Keisuke Itagaki ,he is brought back to life in Japan in our time.

- In the manga Yaiba (城市风云儿, YAIBA) by Gōshō Aoyama, Miyamoto Musashi is one of the main characters of the series. Over 400 years old, he teaches Yaiba Kurogane the art of swordsmanship.

Usagi Yojimbo, by Sakai Stan, Paquet, 2005, 25T, is a nod to the philosophical warrior in the guise of the anthropomorphic rabbit named Miyamoto Usagi (usagi means "rabbit").

Video games

- Brave Fencer Musashi

- Musashi: Samurai Legend

- Sword of the samurai

- Yakuza Kenzan!

- Age of Empires II: The Age of Kings

- Warriors Orochi

- Warriors Orochi 2

- Warriors Orochi 3

- Shining Force

- Samurai Warriors It recounts the internal wars of the Sengoku era in Japan.

- Samurai Warrior 2:Empires

- Samurai Warriors: Xtreme Legends

- Sengoku Basara The story takes place during the period of the wars of kingdoms, or Sengoku period (1467 or 1493-1573), but in an imaginary Japan.

- Sengoku Basara X

- Sengoku Basara: Samurai Heroes

- Sengoku Basara 2

- Sengoku Basara 2 Heroes

- Sengoku Basara 4 (NPC)

- Fate/Grand Order