Ii Naosuke

Share

Ii Naosuke (Japanese 井伊直弼; Ii Naosuke; b. November 29, 1815 in Edo, Japan; March 24, 1860 ibid) was Daimyō of Hikone (1850-1860) and Tairō of the Tokugawa shogunate, a position he held from April 23, 1858 until his assassination on March 24, 1860.

He is best known as a negotiator for the Harris Treaty with the United States. He was also an enthusiastic and accomplished tea master of the Sekishūryū school, and his writings include at least two works on the tea ceremony.

After two years at the helm of the government as Tairō, he was killed in front of the Sakuradamon of Edo Castle on March 24, 1860, by 17 samurai of the Mito order and one samurai of the Satsuma order, in what became known as the Sakuradamon incident.

During Ii Naosuke's tenure, the shogunate was internally divided by two conflicts. The first, domestic conflict flared up over the succession to the ailing and childless shogun Tokugawa Iesada, with two wings within the Tokugawa opposing each other:

on the one hand, the Kishū wing under Ii Naosuke, which supported Tokugawa Yoshitomi (the later Tokugawa Iemochi), and on the other, the Hitotsubashi wing under Tokugawa Nariaki, which supported Hitotsubashi Keiki (the later Tokugawa Yoshinobu).

At the same time, a foreign policy conflict was simmering over how to respond to the threat posed by Western colonial powers, especially the United States.

This pitted the Jōi faction, which rejected any opening of the country and wanted to throw the foreigners out of the country, against the Kaikoku faction, which wanted to open Japan to the world and learn from abroad.

With the possible opening of the country, the future of the Tokugawa shogunate, which had ruled Japan for over 250 years, was also in question.

Ii Naosuke Childhood and youth

Ii Naosuke was born on November 29, 1815, the 14th son of Ii Naonake, daimyo of Hikone, and a mistress. As the 14th son, there was no prospect of a prominent position for him, so he was given to a Buddhist temple where he lived on a small stipend.

From the age of 17 to 32, he lived alone. He developed a teacher-disciple relationship with Nagano Shuzen, who was only a few days older, and studied Confucianism and the teachings of the Kokugaku.

He also studied tea ceremony, waka poetry, taiko, Zen Buddhism (Sōtō-shū), Sōjutsu (spear fighting), and iaijutsu.

By 1850, however, when his father died, his 13 brothers were either given up for adoption to other families in need of an heir or were no longer alive. He was therefore recalled from the monastery, took the name Ii, and was installed as daimyo of Hikone.

Hikone was a so-called fudai fiefdom, that is, traditional ally of the Tokugawa, who did not own much land but were positioned in strategic positions in the country and, more importantly, traditionally provided the shogun's advisors and thus held the decisive positions of power in the shogun, apart from the shogun himself.

Ii became active in national politics and quickly rose to become the leader of a coalition of Daimyō. In 1853, he introduced a proposal into negotiations with Commodore Matthew Perry.

Aware that Japan was "under immediate military threat," he argued that Japan should use its relations with the Netherlands to buy enough time to build an army that could withstand an invasion.

Ii recommended that only the port of Nagasaki be opened to foreigners. Like Hotta Masayoshi, he would not stand still, while Rōjū Abe Masahiro accommodated the anti-foreign faction (Jōi).

After Abe Masahiro negotiated the Treaty of Kanagawa in 1854, an unequal treaty that opened the ports of Nagasaki and Hakodate to Americans, ending over 200 years of Japan's closure, Ii led a group of Fudai-Daimyō who forced Abe to resign.

He was replaced by Hotta Masayoshi. This angered many reformist daimyo, who then strengthened their ties to the imperial court in Kyoto.

Ii Naosuke Reign as Tairō

Harris Treaty

In 1856 Townsend Harris arrived in Japan as the first U.S. envoy, but was quartered far from Edo at Shimoda. He had to endure a total of two years on the Izu Peninsula until he finally negotiated a draft treaty with Hotta Masayoshi and was granted an audience with Shogun Tokugawa Iesada.

The draft provided for the opening of a total of five ports and extraterritoriality for Americans in Japan. It thus marked the final departure from Japan's seclusion and contained clauses typical of unequal treaties.

Ii Naosuke vigorously supported the Harris Treaty and the further opening of Japan, whether to avert a threatened invasion or because he saw opportunities in foreign trade to advance Japan economically and militarily. Following protocol, he asked the Tokugawa-Gosankyō chiefs for a written statement.

In doing so, he encountered opposition from Tokugawa Nariaki, daimyo of Mito. To enforce the Harris Treaty domestically, Ii attempted to gain the approval of Emperor Kōmei. However, Nariaki refused to agree to present the treaty to the emperor.

Although this resistance was overcome and Hotta Masayoshi presented the treaty to the emperor, the project failed because of the Tennō himself, who was a supporter of the Jōi movement.

As a result, Ii Naosuke, with the support of Mizuno Tadanaka and Matsudaira Tadakata, was elevated to the rank of Tairō (regent) by Shōgun Iesada to enforce the treaty.

Thus, Ii Naosuke was now second in the government behind the shogun. (The Ii were one of four Fudai families that traditionally provided the Tairō. Ii Naoaki held the office until 1841, after which the post was vacant).

Harris meanwhile increased pressure on the shogunate to sign the treaty. Ii decided not to enrage the Americans further, and on July 29, 1858, ordered the treaty to be signed. This was done with the support of advisors in the shogunate, but against the wishes of the Tennō.

A short time later, Ii signed similar treaties with the Dutch, Russians, British, and French. A large part of the foreign policy aspirations of the soon-to-be dawning Meiji period was to compensate for the loss of sovereignty established in these treaties and to negotiate with the major Western powers on an equal footing.

Succession to the Shogun

Although Shōgun Tokugawa Iesada was only just over 30 years old, his poor health and childlessness already ignited the struggle for his succession.

The reform wing, led by the head of the Hitotsubashi lineage Tokugawa Nariaki, wanted to see his son Hitotsubashi Keiki as his successor.

Adopted as a child by the Hitotsubashi line of Tokugawa, one of the Gosankyō, Hitotsubashi Keiki had risen to head of the family in 1847 and by then had made a name for himself as an able administrator.

The reform wing hoped that he would continue the renewals in the spirit of the Mito school. Among his supporters was the influential daimyo of Satsuma, Shimazu Nariakira.

Ii Naosuke, however, wanted to prevent the continuation of the reforms, seeing in them a weakening of the central power of the shogunate bureaucracy. Instead, he supported Tokugawa Yoshitomi, the daimyo of Kii who was just 12 years old and thus head of one of the gosanke.

He hoped that such a young shogun would be easier to control. After the signing of the Harris Treaty, Ii turned to the question of succession.

He used his position as Tairō to curtail the influence of the Shinpan-Daimyō (the Tokugawa collateral lineages) and the imperial court in Kyoto on this issue, and instead decided for himself as the shogun's chief minister. In doing so, he was able to prevail and, after Iesada's death in 1858, install Yoshitomi as the 14th shogun, Tokugawa Iemochi.

This decision made Ii very unpopular with the imperial court and with reformers, especially in Mito. The reformers turned to the emperor to keep Ii in check. Ii responded before Iesada's death with a shogun decree that allowed him to remove his opponents from their posts.

During the Ansei purges, he removed over 100 shogunate officials up to daimyo and even ministers and courtiers at the imperial court from their posts. Among them were many followers of the Mito school, including the Hitotsubashi family, as well as opponents of the Harris Accords. Eight people were executed.

Kōbu gattai and the marriage of Iemochi and Kazunomiya

Kōbu gattai refers to the attempt to bind the shogunate and the imperial court together, thus restoring the shogunate's diminished prestige and creating a stronger central power in Japan, which was under pressure from outside.

As a symbol of this movement, the young shogun Iemochi was to be married to a half-sister of the emperor, Kazunomiya. Although marriages between high-ranking samurai and court nobles were a common means of forging alliances, it was more common to give women from the nominally lower rank, that is, the samurai, to the nominally higher rank, that is, the court nobles.

The only comparable case of a direct connection between the imperial house and the Tokugawa was the marriage between Emperor Go-Mizunoo and Tokugawa Masako at the beginning of the Edo period.

A marriage between Iemochi and Kazunomiya was proposed to Ii as early as 1859 by Nagano Shuzen, his representative at the imperial court. He then instructed his envoy Manabe Akibuke to propose this marriage to the emperor.

The court official Konoe Tadahiro signaled his support on the condition that Kazunomiya's existing engagement be dissolved. However, Konoe was removed from his posts in March 1859 by Ii's ansei purge, so this idea was not pursued further. It was only after Ii's death that this marriage was finally consummated in 1861.

Ii Naosuke Assassination

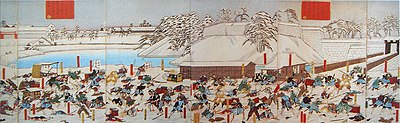

Although the Ansei purges effectively eliminated Ii's opponents in the high ranks, he made all the more enemies in the lower samurai ranks. After 20 months in office, he was killed in an assassination attempt on him and his porters and bodyguards outside the Sakurada Gate of Edo Castle on March 24, 1860.

This assassination, which became known as the "Sakuradamon Incident," was carried out by 17 samurai from Mito as well as Arimura Jisaemon from Satsuma. Arimura, who severed Ii's head with a blow, was seriously wounded and committed suicide on the spot.

With this attack, the central power figure of the shogunate and the symbol of its power and authority was killed. This marked the end of the last peak in the shogunate's power, and it would not recover from this blow.

In the aftermath of the attack on the Tairō, there was a wave of attacks by Tenno loyalists throughout Japan. The poet Tsunada Tadayuki even wrote a hymn in praise of the assassins.

Attacks were made on other officials of the Bakufu and its informants. The counter-movement was also directed against court officials associated with Ii Naosuke.

Among others, Shimada Sakon, head of the Kujō (one of the Go-Sekke, the five regent houses of the Fujiwara) and imperial regent, was killed for his support of the Harris Treaty and his aiding and abetting of denunciations during the Ansei purges.

The young shogun and the shogunate administration were completely surprised and overwhelmed by the attack.

Attempts were made to cover up the true events, first pretending that Ii was still alive, then faking illness and his resignation from office. His death was not announced until months later. Later, Ii's assassins were pardoned in a general amnesty by the Bakufu.

Ii Naosuke's successor as daimyo of Hikone was his second son Ii Naonori in 1862. However, the Han's property was cut by about a third from 300,000 koku to 200,000 koku as punishment for the Ansei purges.