Tsukumogami

Share

Tsukumogami (jap. 付喪神, occasionally 九十九神, "artifact spirits") are beings of Japanese folk belief. They represent a special group of the Yōkai: They are various ensouled utilitarian and everyday objects that are said to become Yōkai and come to life.

According to tradition, tsukumogami are "born" after 100 years have passed, if the object in question has been neglected and/or carelessly discarded.

The belief in their existence can already be found in writings of the Heian period, these beings experience their heyday during the late Edo period.

At the beginning of the spreading of the belief, which originates from the Shingon-shū (the Chinese tradition of the Mizong school) and found its way into Shintoism, Tsukumogami are described as vengeful and bloodthirsty.

In later writings, especially those of the Edo period, the character of the artifact spirits was more and more downplayed until they were and are portrayed and parodied in countless novels, mangas, movies, and even kabuki plays since about the middle of the 20th century.

Even today, some tsukumogami are still well-known and popular in Japan, especially among children and young people.

Tsukumogami Etymology of the term

The origin of the term tsukumogami and its spelling with the kanji 付喪神 (literally "grief inflicting god") is not certain. It is generally believed that the characters used represent a consonance with the syllabic sequence tsukumogami (つくもがみ).

On the one hand, when Chinese characters were used to represent this phonetic sequence, the characters 九十九髪 (literally "hair of 99 [years of age]") were commonly used. Written in this form, the term poetically refers to the hair of a 99-year-old or 99-year-olds and is symbolic of a very long life.

Tsukumo, in turn, is a contraction of tsugu ("next") and momo ("100"). The 99 [years] was also chosen because the character 白 for "white" resembles that for "hundred" 百, which lacks the upper stroke, which in turn resembles that for "one" 一.

The character 白 for "white" resembles that for "hundred" 百, which lacks the upper stroke, which in turn resembles that for "one" 一.

On the other hand, this sequence of syllables is again closely related to a poem from the 63rd episode of the Ise Monogatari, which depicts a man's relationship with an old woman.

The term tsukumogami is used for the woman in the poem to indicate that her hair is many years old. Tsukumo, in turn, is an old name for the zebra lime (Scirpus tabernaemontani), whose inflorescence is reminiscent of the hair of an old person.

Takako Tanaka suggests that the spelling of this old woman's name with the kanji 付喪神 arose from つくも髪 (meaning "hair of 99"), in order to emphasize by its use the menacing character of the woman who inflicts painful suffering on Ariwara no Narihira during nighttime forays.

In the Tsukumogami ki (see later in the text), the kanji 付喪神 were then used to designate the "artifact spirits."

Noriko T. Reider suggests that the use of this spelling is a deliberate allusion to a 4th or early 5th century Chinese text entitled sōu shén jì (捜神記; dt. "In Search of Gods").

The Japanese reading of these characters is Sōshin ki. The on reading of the kanji 付喪神記 is Fusōshin ki, which in turn is a homonym for fu Sōshin ki (Eng. "Supplement to Sōshin ki").

The content of this interpretation is supported by the fact that the "artifact spirits" of the Tsukumogami ki first worship a Shintōist creator god, only to find their salvation in Shingon Buddhism.

According to Kazuhiko Komatsu, the second spelling of "artifact spirits" with the kanji 九十九神 (literally "deity of 99 [years of age]") derives from the fact that 九十九髪 means "longevity" and that special powers were acquired through this longevity.

The pronunciation of the kanji 髪 (meaning "hair") and 神 (meaning "deity") is homonymous and thus in both cases the pronunciation is Tsukumogami. By spelling 九十九神, spirit beings are symbolized that are imprinted by people or objects of very old age and become ghosts as soon as something mysterious occurs as a result of their actions.

Definition of Tsukumogami

The belief in tsukumogami and their work originates from a certain form of Buddhism, Shingon-shū, but is also represented in Shintōism. Both religions teach that even seemingly dead objects can be "animated" and transformed at any time, because they also possess a soul.

These seemingly dead objects, like humans or the souls of the deceased, acquire supernatural, magical abilities when they reach a very high age and, if they are honored and respected accordingly, can change into a "different world" as kami (spirit beings).

The belief in "ensouled" natural objects was transferred to man-made objects (artifacts) during the 14th century at the latest, and spread throughout Japan.

According to ancient Japanese folk belief, tsukumogami are thus Yōkai that develop after the lapse of 100 years if the object in question has not been disposed of with the respect it deserves after a long period of use and the soul inherent in the object is not honored as kami.

Or it is objects in use that are at least 100 years old ("have reached their 100th birthday") and are not honored, or rather neglected, according to their great age. In this form, the tsukumogami spread fear and terror among people and play nasty jokes on their former owners, but are ultimately rather harmless.

However, when these Yōkai become shapeshifters through a special Shintōist ritual and gain magical powers comparable to oni (demons), they can become bloodthirsty monsters and exact cruel revenge on humans for the dishonor done to them.

Typical objects that can become kami or Yōkai include household items (for example, lanterns, tea kettles, and futons), everyday objects (for example, watches and umbrellas), clothing (for example, coats and sandals), and musical instruments (for example, biwas, shamisen, and gongs).

It is striking that even modern folklore only ever brings to life handmade artifacts that are powered or used without electricity. This is probably based on a desire to return to old traditions and values, as is still widespread in Japan today.

Tsukumogami's Character

Usually tsukumogami are described as harmless creatures with a childlike character, who only seek attention through their activity.

Through their behavior, which is very reminiscent of poltergeist activities of Western cultures, tsukumogami, according to folklore, want to remind their former owners that they must take care of their household and all the objects and artifacts in it.

Consequently, the actual main motives are boredom and sorrow. Many tsukumogami are said to, at best, simply leave the house and run away if they continue to be ignored.

On the other hand, if tsukumogami are created by careless and inconsiderate disposal on the part of their former owners, they may pursue them, as they are initially driven solely by pent-up frustration.

Envy is also said to play a role, but this is directed against newly acquired household items that were supposed to replace the old ones. For this reason, it is not uncommon for tsukumogami to wreak havoc in the affected home.

Most tsukumogami initially play silly pranks on the residents in whose households they were "born".

If, on the other hand, they have been treated badly, they are driven by anger and vengefulness, take on violent traits, and attack the occupants of the house. Many tsukumogami are said to enjoy gathering with other-formed artifact spirits and then throwing downright parties.

History of Tsukumogami

Prehistory and literary origins

The earliest mention of animate, ghostly household objects is found in literature of the late Heian period (794-1184) from the 12th century, for example in two tales from the Konjaku Monogatari shū (今昔物語集, Eng. "Anthology of Ancient Tales"), recorded around 1120.

In one case, it concerns a copper decanter whose spirit transforms into a human being and who asks that the decanter, already buried, be dug up again. In another case, a malevolent oni takes possession of a small oil pot and kills a sick girl in this form.

Other tales from the same period also tell of objects that were infested with evil spirits and in this form caused harm to people. In the early accounts, the objects predominantly do not become spirits themselves, but are possessed by strange spirits.

The first known pictorial depiction of tsukumogami is found in the pictorial scroll Tsuchigumo no Sōshi Emaki (土蜘蛛草紙絵巻, Eng. "Pictorial Scroll of the Tale of the Spider") from the late Kamakura period (1185-1335).

This scroll tells of Minamoto no Yorimitsu's battle against a mythical giant spider. In the entryway of the house inhabited by the spider, various ghosts, including tsukumogami, attempt to prevent Yorimitsu from proceeding.

In illustrated texts from the Muromachi period (1336-1573), tsukumogami were first described in more detail.

It was also during this time that they received their designation as tsukumogami and are exclusively spirits inherent in the objects themselves. The idea that tsukumogami were possessed by spirits or oni is explicitly rejected as false by the authors of the texts.

The texts belong to the genre of Otogizōshi (engl. "entertainment books") and have survived in several handwritten copies from the end of the 15th century.

They bear various titles, such as Hijō jōbutsu emaki (非情成仏絵巻, Eng. "Illustrated Handrolls on the Attainment of Buddhahood by Unconscious Living Beings"), Tsukumogami ki (付喪神記, Eng. "Record of Spirits of Household Objects"), Tsukumogami (付喪神, Eng. "Spirits of Household Objects"), and Tsukumogami emaki (付喪神絵巻, Eng.

"Illustrated Handrolls of Spirits of Household Objects"), and are collectively referred to as Tsukumogami ki.

The texts were written in an entertaining form and, according to Noriko T. Reider, with the intention of spreading the teachings of Shingon Buddhism. It is likely that other copies existed beforehand, circulating in aristocratic circles.

Other depictions of tsukumogami are found on picture scrolls commonly referred to by the term hyakki yagyō emaki (百鬼夜行絵巻, Eng. "Illustrated hand scrolls of nocturnal processions of 100 spirits").

According to Elizabeth Lillehoj, such pictorial scrolls would have existed as early as the 14th century and possibly earlier. The pictorial scrolls depict the procession of numerous different Yōkai parading through the streets of cities after midnight, terrifying the people.

The ghostly marches are described as early as the Ōkagami (大鏡, Eng. "The Great Mirror," ca. 1085-1125) and the Konjaku monogatari shū, though without the spirits involved being described in these texts themselves.

The oldest surviving image scroll of this type is located in the Shinju-an branch temple on the grounds of Daitoku-ji in Kyōto. According to a disputed attribution, it was made by Tosa Mitsunobu (ca. 1434-1525) and is consistently dated to the first half of the 16th century. Many of the Yōkai depicted on this scroll are tsukumogami, such as a kasa-obake or a bake-zori.

Tsukumogami in Bloom

During the Edo period (1603-1868), the legends and anecdotes about tsukumogami reached their peak. By the beginning of the Edo period, at the latest, belief in tsukumogami had spread to the common people.

Numerous legends, which were recorded by folklorists in the 20th century and received the generic term Bakamono-dera (化物寺, Engl. "ghost temple"), tell of abandoned temples or houses in which ghosts walk around at night.

A priest, a passing wanderer, or even a local villager finds himself compelled by adverse circumstances to spend the night in the haunted temple or house, and is haunted there by ghosts and demons.

The visitor manages to appease the spirits (in some cases they are killed) and thus free the building from its curse. In one story, these are the spirits of an old straw cloak, an old straw hat, an old bell, and an old drum; in another, the spirits of a gourd, a parasol, a lance shaft, a tray, and two lumps of ash.

In other versions of the bakemono-dera collected by Yanagita Kunio, for example, the spirits of old, wooden geta, an old mortar, and an old wooden hammer appear.

Numerous written works were composed that were specifically devoted to tsukumogami and also depicted them, but without portraying them as bloodthirstily as they had been depicted in previous descriptions.

Literary mention of tsukumogami was found, for example, in the Sorori monogatari (曾呂利物語, Eng. "Tales of the Sorori," c. 1620). In it, the story is told of a clever monk who can prophesy about tsukumogami based on their names, from which object they originated.

Among other things, he names the Enyōbō, which has the shape of a gourd. The most comprehensive, Edo period account and description of Yōkai in general and tsukumogami in particular is found in the work of Toriyama Sekien, who published four books of several volumes each between 1776 and 1784.

The rapid succession of publications and the numerous new editions, often under slightly different titles, attest to the great popularity that the spirit world enjoyed in Japan toward the end of the 18th century.

In the books Hyakki yagyō (百鬼夜行, Eng. "Nocturnal Procession of 100 Ghosts," 1776), Zoku hyakki (続百鬼, Eng. "Continuation to the 100 Spirits," 1779), Hyakki yagyō shūi (百鬼夜行拾遺, Eng. "Gleanings to the Nightly Processions of the 100 Spirits," 1781),

and Hyakki tsurezure bukuro (百器徒然袋, Eng. "Sackful of Casual 100 Spirits," 1784), Sekien describes in detail the well-known Yōkai and thus some tsukumogami of his time, adding anecdotes to almost all of them passed down in writing or orally.

Other tsukumogami he made up himself, and it was through his work that he first made them known and popular. In general, a remarkable growth of legends surrounding tsukomogami (and other Yōkai) can be observed during the Edo period.

Towards the end of the Edo period, tsukumogami also found their way into the kabuki theaters of Edo and Ōsaka, as evidenced by depictions of such scenes in contemporary woodblock prints by Utagawa Kunisada and Konishi Hirosada.

One tsukumogami known and depicted to this day comes from the kabuki play Tōkaidō Yotsuya Kaidan (東海道四谷怪談, Eng: "Ghost Stories in Yotsuya on the Tōkai Road," which premiered in 1825).

The play is about a woman named Oiwa nyōbō Iemon who is driven to her death by her husband, his family, and her concubine. Her ghost first appears as a paper lantern in the final scene of the play, emerges from it, and takes revenge on her mother-in-law and husband, Tamiya Iemon.

This ghost is captured as Chōchin Oiwa, a special form of Chōchin-obake, in numerous woodblock prints by Katsushika Hokusai, Utagawa Kunisada, and Utagawa Kuniyoshi, the leading woodblock artists of their time, and is still known in Japan today.

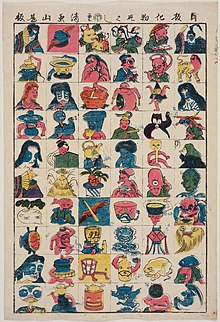

Tsukumogami are also found on other woodblock prints from the end of the Edo period. At least two Sugoroku game boards, one by an unknown artist and one by Utagawa Yoshikazu, survive.

In the collection of the Boston MFA is a print by Hiroshige's student Kiyoshige, titled Shinpan bakemono zukushi (新板化物づくし, Eng. "A New Collection of Ghosts"), which depicts 60 different ghosts, including numerous tsukumogami, in a manner appropriate for children.[31] The print is a very popular one.

Tsukumogami in Present

As Komatsu reports, it was long customary in Japan to celebrate a special New Year's festival for household items on the 14th or 15th day of the first month, honoring them with offerings.

This custom has since fallen into disuse, but to this day, a type of festival called Susuharai (煤払い; transl. "Its origins can be traced back to the early 13th century.

In the course of the festival, houses and households are thoroughly cleaned both in terms of purification and ritual. Especially by older Japanese, old or broken items (e.g., furniture, wardrobes, dolls, and musical instruments) that are to be replaced with new ones are first taken to a nearby shrine to be blessed.

The items undergo a formal ceremony (供養, Kuyo) before being given away or disposed of in the bulky waste. This is said to prevent tsukumogami from being "born" in one's own home.

Another tradition that may tie to the fear of tsukumogami is that of, for example, embedding broken or worn knitting needles in tofu cubes and bidding them a dignified farewell.

Legends and Folklore of Tsukumogami

In the Tsukumogami ki (付喪神記, meaning "Record of Spirits of Household Objects") from the Muromachi period, it is described how objects carelessly removed from the household gather and deliberate their fate.

The objects decide to take revenge on humans for the dishonor done to them and to be transformed into animate beings by the power of a Shintōist creator god. The only voice of dissent on the part of a discarded Buddhist rosary, but better to answer hostility with kindness, they throw to the wind.

The objects undergo the Shintō ritual and thereby become animated, vengeful tsukumogami. They take different forms: They become young or old men or women, animals (such as foxes or wolves), demons, or goblins. What all the figures have in common is that they are terrifying beyond description.

The spirits settle behind the mountain Funaoka and from there they repeatedly attack the capital and its surroundings, where they kill the people and their pets and take their victims as food.

They build a castle of flesh and construct a well from which blood flows. They commit diabolical acts and are aggressive against everything human.

To put a stop to their terror, a Buddhist ritual finally takes place at the imperial court, as a result of which "Divine Boys", the companions of the "Protectors of the Doctrine", appear and take up the fight against the spirits.

However, the "Divine Boys" do not destroy the spirits, but take an oath from them to desist from their revenge on humans and to go on the way of the Buddha. The spirits keep their oath, retreat to remote mountain valleys, and eventually attain all Buddhahood after extensive study.

Modern anecdotes surrounding tsukumogami are also common in Japan today. In Ehime Prefecture, for example, there is a legend that a bewitched umbrella in the Higashimurayama district tempts unsuspecting walkers caught in a downpour to open the umbrella in order to supposedly protect themselves from the rain.

But instead, the kasa-obake grabs its victims by the wrist and carries them away for miles.

In Japan, many parents still tell their children that a Chōchin-obake will lure them from their beds at night and carry them off. Presumably, such scary stories are meant to discourage children from wandering around at night and not wanting to go to sleep.

Tsukumogami in modern subculture

Tsukumogami today

Notions and images of tsukumogami are popular in modern Japan even apart from traditional beliefs; they are popular as fictional characters. Various artifact spirits are well known and experience a corresponding level of recognition, especially among children and young people.

This is partly due to the fact that tsukumogami such as Bake-zōri, Kasa-obake, and Chōchin-obake embody those household and everyday objects that are still in daily use today, making it easier to remember their likenesses.

Modern media

The enduring popularity surrounding tsukumogami can be explained primarily by the fact that tsukumogami and other yōkai are not only repeatedly thematized in illustrated novel literature,

but now also appear in modern media such as anime series, manga, kabuki theaters, horror films, computer games, and even as toys. The tsukumogami are still used in many households today.

Many tsukumogami characters are common in Japan as toys and as designs on trading cards. For example, jumping jacks in the form of the kasa-obake are sold.

Their regular appearance in modern media effectively perpetuates and promotes the familiarity and popularity of tsukumogami among young people.

In the case of certain artifact spirits, such as the kasa-obake, their familiarity is also explained by the fact that their appearance is easy to describe and trace, which is why these beings are popular among children and young people as painting and sketching subjects.

In the early 1970s, tsukumogami became a popular subject for children and young people.

In the early 1970s, tsukumogami such as the kasa-obake made a kind of modern comeback in the modern film industry. Kasa-obake appear in various Yōkai films, such as Yōkai Hyaku Monogatari by Yasuda Kimiyoshi in 1968, and are given prominent roles in the film.

In the 1966 fantasy horror film Yōkai Daisensō (Great Yōkai War) by Yoshiyuko Kuroda, the Yōkai boy GeGeGe no Kitarō travels to the human world to find a hero to save the monster world from vicious tsukumogami and treacherous Yōkai.

In contrast, in Miike Takashi's 2006 remake, a young Tokyo boy is drawn into a war between benevolent Yōkai and vicious tsukumogami.

Animated house and everyday objects brought to life are also recurring themes in countless anime series and films, such as Chihiro's Journey to Magic Land, where a Chōchin-obake in the form of a one-footed court lantern bounces toward Chihiro during her visit to Witch Zeniba to light her way to the witch's house.

In the manga Tsugumomo, humans fight together with tsukumogami against spirits that possess humans.

A well-known presentation of various tsukumogami in computer games can be found in the Game Boy game Super Mario Land 2.

There, entire levels (for example, Pumpkin Zone) are dedicated to various Yōkai and tsukumogami. Tsukumogami that ambush the protagonist Mario there are the Chōchin-obake and the Kasa-obake.

While the Chōchin-obake hovers motionless in the air and merely tries to hit Mario with its long tongue, the Kasa-obake leaps high into the air, stretches its umbrella, and flies nimbly after the hero.

Another example is the video game Tsukumogami (English title version: 99 Spirits), which is set in feudal medieval Japan and is about teenage demon hunters. The game's main theme is the tsukumogami.

Parallels in Western film and entertainment media

The notion of animated and animate objects is also found in Western culture. Especially animated and fantasy films, which were designed and released by Walt Disney Studios, show clear parallels to tsukumogami appearances in certain individual scenes, according to authors such as Patrick Drazen.

A prime example is Disney's Beauty and the Beast: In the Beast's castle, animated household objects and dishes are up to mischief. Whether and to what extent Japanese culture has influenced these Western notions, however, is unclear.

Known Tsukumogami

Among the most famous and popular tsukumogami are:

- Bake-zōri: walking rice straw sandals with two arms, two legs, and one eye. They are said to run around the house at night singing loudly.

- Biwa-bokuboku: A soulful Biwa who is said to awaken at night and play and sing loudly wailing. She laments her neglect.

- Boroboroton: A dingy futon that comes to life and wraps itself around the sleeper to strangle him.

- Chōchin-obake: An ensouled Chōchin lantern that frightens unsuspecting wanderers and householders.

- Kameosa: An ensouled sake jar that never runs dry if treated well.

- Kasa-obake: A possessed paper umbrella with one leg, two arms, one eye, and a long tongue.

- Koto-furunushi: A possessed koto that is said to play by itself when no one is looking.

- Zorigami: Possessed watches that torment their owners by constantly telling them the wrong time on purpose.