Takeminakata

Share

Takeminakata-no-Kami (建御名方神) or Takeminakata-no-Mikoto (建御名方命) is a Shinto deity, but is also known as Minakatatomi-no-Kami (南方刀美神 ), or Takeminakatatomi-no-Mikoto (建御名方富命), whose name appears in the Kojiki and derived sources.

These describe him as one of the sons of the god of Izumo Province and the lord of Asira no Nakacukuni (the mythological name of Japan), Ókuninuni. After he was defeated by Takemikazuichi, an envoy sent by the heavenly kami, he retreated in exile to the Suva region in Sinano Province (present-day Nagano Prefecture).

Izumoi Takeminakata is generally identified with the High Deity of the Great Shrine of Suva and is most often referred to as the Suva (Dai)myojin (諏訪(大)明神).

He is the god of wind, water and agriculture, as well as the patron of hunting and warfare, and was held in particularly deep religious veneration by many samurai families during the Middle Ages, such as the Hojō and the Takeda family.

In a sense, Suwa Myojin is also considered to be the ancestor of some of the families that once served as priests at the shrine, the Suwa family being the foremost of these.

Takeminakata Etymology

The god is called Takeminakata-no-Kami (建御名方神) in both the Kojiki and the Sendai Kuji Hongi (also known as the Kujiki). Various variants of the name can be found in other literary sources including Minakatatomi-no-Kami (南方刀美神), Minakatatomi-no-mikoto-no-Kamit (御名方富命神) or Takeminakatatomi-no-Mikoto(-gamit) (建御名方富命神).

The etymology of the name is unclear. While most scholars agree that take- (and probably -tomi as well) are honorific titles, opinions differ on how the rest of the name should be interpreted. Some possible versions are given below.

- A follower of the Kokugaku school, Motoori Norinaga, has explained that both take- (建) and mi- (御) are honorific titles (称名 tatae-na), with the kata sign (方) added, as tatae-naban has the meaning "tough", "resistant"(堅). Basil Chamberlain, following Motoori, referred to the god as "Brave-August-Name-Hard" in his translation of the Kodjiki.

- The historian Óta Akira (1926) interpreted take-, mi- and -tomi as honorific titles and took Nakata (名方) as if it were the name of a locality: that of Nakata District in Ava Province (present-day Tokusima Prefecture, Isí), where Takeminatomi Shrine (多祁御奈刀弥神社) stands. The writer Ova Ivao (1990) also suggested a similar connection between "Takeminakata(tomi)" and "Takeminatomi", claiming that the name was probably brought to Suva by immigrants from Nakata in Avai.

- Minakatata has also been linked to the Munakata (宗像) of Kyushu. The Japanese Imperial Navy colonel and amateur ethnographer Macuoka Sizuo interpreted Minakatatomi as originally meaning the name of a goddess - highlighting the fact that the deities of the Munakata Shrine were all female - which was later combined with the name of the male god Takeminakata.

- Several more recent scholars have theorized that the word mina probably means "water" (水), suggesting that Takeminakata was originally associated with an aquatic deity and/or Lake Suva. It was thought that the full name was derived from a word denoting a body of water or a waterfront region, such as 水潟 (minakata, 'lagoon' or 'narrow bay') or 水県 (mina 'water' + agata 'countryside').

- An alternative interpretation of the word -tomi (as well as -tome in Yasakatomé) is that it can be associated with certain vernacular words for snake (tomi, tobe, or tobe), thus suggesting that the god is a kind of water-snake deity (mizucsi).

Suva Myodzin

A commonly used epithet for the god worshipped as a saint at the Great Shrine of Suva - specifically the Kamisa or Upper Shrine in the southeastern area of Lake Suva - has been Suva Myojin (諏訪明神) or Suva Daimyo Jin (諏訪大明神).

This name is also applied as a catch-all to the shrine itself. This variant is associated with the syncretistic Ryobu Shinto sect, Suva Hosso Daimyo Jin (諏訪(南宮)法性(上下)大明神), or the Darma Nature Daimyo Jin of the Upper and Lower Suva Shrine, as it appears on some of the battle flags of, for example, Sengoku Takeda Singen daimyo (a fervent devotee of Takeminakata).

The Nihonsoki (dating from 720 AD) speaks of imperial envoys sent to Shinano in the 5th year of Empress Zhito's reign (691 AD) to worship the wind gods of the Tacuta Shrine, or "Suva and Minochi".

Thus suggesting that the god worshipped in the Suva region (須波神 Suva no kami) was already worshipped as a water and/or wind deity in the Jamato imperial court during the late 7th century, alongside the wind gods of Tacuta Shrine in Jamato province (present-day Nara prefecture)

Suva Myojin's connection with Takeminakata was undoubtedly established at the earliest around the 9th century. The Kuji Hongi (collected between 807-936 AD) refers to Takeminakata as being venerated at the shrine of Suva (信濃國諏方郡諏方神社) in Suva District within Sinano Province, usually in reference to the Great Shrine of Suva, where Suva Myojin is venerated as a saint.

The Nihon Sandai Jicuroku, written at about the same time and covering the years from 858 to 887, also refers to the Takeminakatatomi no Mikoto Shrine of Suva (建御名方富命神社). The introductory section of the Ekotoba of Suva Daimyo Jin (hereafter referred to as Ekotoba), written in 1356, unmistakably links Suva Myojin with the Takeminakata of Izumo.

This identification is, however, somewhat difficult to make on the basis of legends from medieval sources and hagiological research (some of which has been recorded in Ekotoba), which also identify Suva Myojin with figures such as the folkloric Koga Szaburo (甲賀三郎).

A man who returned from a journey to the underworld to find himself transformed into a serpent/dragon or king of India, and then attained enlightenment and went to Japan (see below under Legends of Suva Myojin). As well as the fact that many of the religious rituals of the Suva Kamisa actually involved the worship of a god, Misaguji.

To reflect this distinction, the name "Izumoi Takeminakata" will be used hereafter to refer to the god described by Kodjiki, the Kuji Hongi and other sources, while the name "Suva Myodjin" will be used when referring to the god of the Great Shrine of Suva.

Takeminakata in mythology

Ancestry

Takeminakata-no-Kami (建御名方神) is depicted in both the Kodjiki and the Kuji Hongi as the son of an earthly deity, Ókuninusi, ruler of the Izumo province. His mother is depicted in the Kuji Hongi as one of Ókuninusi's wives, Kosi no Nunakavahime (高志沼河姫 Kosi no Nunakavahime).

Takeminakata and Takemikazu

Takeminakata appear in the context of the Kojiki and the Kuji Hongi as an Old Kunin mediator (kuni-juzuri) between the earth and the sky gods (Takamagahara).

When the gods of Takamagahara send Takemikazuci and another messenger to urge Ókuninusi to relinquish his authority over the Asira no Nakacukuni to the successor of the Sun Goddess Amaterasu, he is asked to consult with two of his eldest sons before making his decision.

While his first-born son Kotosironusi immediately obeyed the summons, advising his father to do likewise, his second-born son Takeminakata, carrying a huge boulder (千引之石 csibiki no isi, which was so large it took 1,000 men to lift it) with the fingertips of one hand, challenged the messenger Takemikazuji to a test of strength by grasping his hand.

After Takeminakata grabbed Takemikazuichi's hand, he turned it into an icicle and then into a knife blade, forcing Takeminakata to let go. In return, Takemikazuji grabbed Takeminakata's arm and crushed it like a reed and tossed it aside. Chased by the heavenly messenger, the wounded Takeminakata fled in fear.

On arriving at the Suva Sea in Sinano Province (科野国州羽海), Takeminakata, pleading for his life, vowed that he would not leave Sinano territory on any pretext.

The introductory part of the Ekotoba of the Suva Daimyo Jin retells the grand myth as recorded in the Kuji Hongi, although omitting the detail that describes Takemikazuichi wounding Takeminakata, who then flees to Suva in shameful defeat.

The legends of Suva Myojin

The following are examples of some stories and folk beliefs about Suva Myodzin, the High Deity of the Great Shrine of Suva. Depending on the story, the deity may or may not be the same as Takeminakatai Izumo.

Takeminakata Source :

The Mizogi Hori

In the Meiji period, before the abolition of the traditional priestly offices of the Great Shrine of Suva, a son served as the high priest of the Suva family, or ohhori (大祝 or ohhafuri), in the Upper Shrine, or Kamisa. In addition to being the high priest of the shrine, during his tenure the boy was worshipped as a living god, and as the reincarnation of Suva Myojin himself.

Legends claim that the office was established when Suva Myodzin, described as an entity without a physical body, appeared in a vision to an 8-year-old boy and appointed him as his priest and living manifestation.

The boy was then clothed in the god's own robes, thus becoming a miszogi-hori (御衣着祝), or priest "one who wears the sacred robe", and the forerunner of the position of Kamisai ohori.

Most sources identify this child with the semi-legendary figure Arikazu (有員), who lived in the early 9th century, sometime during the reigns of the Japanese emperors Kanmu (781-806), Heizei (806-809) or Saga (809-823), respectively.

It is even sometimes suggested that Arikazu was the son of Emperor Kanmu himself.

However, from a large number of surviving family trees of the Suwa family (大祝家 神氏系図 Ohóri-ke Jinshi Keizu) found in the Suwa high priest's residence and discovered by a government-appointed priest, Nobukava Kazuhiko (延川和彦) in 1884, (Meiji 17. year), and the genealogy (異本阿蘇氏系図 Ihon Aso-shi Keizu) of the Kyushu Aso Shrine Aso family (阿蘇) is also claimed to be the first,

Otoei (乙頴) was instead an individual known as Otoei (神子 or 熊古) or by another name Kumako, the son of kuni-no-mijacuko Mase-no-kimi (麻背君), a kuni-no-mijacuko who lived in Sinano province during the reign of the Yomei emperor (585-587). Jinsi Keizu refers to Arikazu as a descendant of Otoei/Kumako.

The testimony of these two genealogies has led many writers to believe that Arikazu was historically very likely a descendant of the Heian-era Otoei/Kumako.

He was the first Oghorian to revive the priesthood, which he began with his descendant. However, recent reassessments of the two genealogies (especially those of the Aso family tree) have cast doubt on their authenticity and reliability as historical sources.

King of India

A medieval Buddhist legend portrays Suva Myojin as originally ruling over a certain kingdom in India, and later attaining enlightenment and going to Japan to become an ancient kamiva.

One version has been linked to the monoimi no rei no koto (諏訪上社物忌令之事, henceforth, referred to as just Monoimi no rei) of the Suva Kamisa, a record of the decrees or prohibitions (物忌み monoimi) of the High Sanctuary, originally enacted in 1238,

of Suva Myojin as the Indian Hadai (波堤国 Hadai-koku; Hatthipura), who survived a coup attempt led by his rebel minister, named 'Morija' (守屋 or 守洩), taking advantage of the king's absence during a deer hunt.

He later became ruler of Persia after defeating a dangerous dragon there. Ruler Suwa (陬波皇帝 Suwa Kōtei) cultivated the drive of virtue and came to realize the Buddhist path, then travelled eastward to Japan, where he became known as the deity Takeminakata Myojin (守屋 or 守洩).

The Ekotoba of Suva Enchu Suva Daimyo Jin tells a slightly different, fuller story in its first half. Here, as he is nearly killed by the armies sent by the rebel Hadai king Bikyo (美教), he rings a bell, cries out eight times to heaven, and announces that the deer hunt was nothing more than a way to lead to enlightenment.

The god Brahma sends the Four Heavenly Kings to crush the rebellion. This version then explains the name of the sacred bell, Yasaka no Suzu (八𠮧鈴), one of the treasures of the Suva Kamisai, which is derived from the king's eightfold cry to heaven, and the four Onbashiras (four wooden poles or pillars standing on the corners of the shrines of Lake Suva, symbolizing the four kings who came to his aid).

And the hunting festival of the Shrine of Suva, known as Misajama (御射山, here spelled 三斎山 - because the ritual is believed to purify (斎) three sins: sinful thoughts, sinful words and sinful actions), is a re-enactment of the king's hunt, performed out of mercy to save sentient beings.

In contrast, the Suva Daimyo Jin Kosiki (also by Enchu) focuses on the slaying of the dragon in Persia and the subsequent quest for enlightenment and immigration of the ruler Suva to Japan.

An unoriginated, and therefore less credible but not negligible alternative history of Suva Myojin adds some details, such as that the king himself is the grandson of King Sihahanu (獅子頬王), the grandfather of Gautama Buddha. It also adds that the evil Bikyo - here called Bikyo Daijin (美教大臣) - goes to Japan and then becomes Moreja, an outlaw of the evil law.

Kóga Szaburó

This is a popular story, spread by wandering preachers during the Middle Ages about the shrines of Suva, which claims that Suva Myojin was originally a mortal man who turned into a dragon after an underworld journey. There are many versions of the basic story. The following summary is based on the earliest literary version of the narrative, found in the Sintōsū (神道集)

The third son of a local Omi province landlord of the Kōka district, a prominent warrior named Kōga Szaburo Jorikata (甲賀三郎諏方) was searching for his missing wife, Princess Kasuga (春日姫 Kaszuga-hime), in a cave with his two brothers in Sinano, on Mount Tatesina.

The second brother, jealous of Szaburo's bravery and reputation, trapped the latter in the cave after they rescued the princess.

With no way out, Saburo had no choice but to continue deeper into the cave, which was actually the entrance to several underground realms. After a long journey through these underground landscapes, he finally found the path that led him back to the surface.

Once on the surface, he found himself transformed into a giant snake/dragon. With the help of Buddhist monks, Saburo regained his human form and was finally reunited with his wife. Szaburo eventually became Suva Myojin, the goddess of the Upper Shrine of Suva, Kamisa, while Kasuga became the goddess of the Lower Shrine, Simosa.

This version of the legend explains the origin of the name Suva (諏訪 or 諏方) through folk etymology, as being derived from the personal name of Szaburo, Jorikata (諏方).

The defeat of Moreja

A local legend claims that Suva Myojin originally faced opposition from the god Moreja, who challenged the newcomer equipped with a weapon made of iron - variously identified as an iron ring (鉄輪)sometimes an iron hilt (鉄鎰,[32][72][73] 鉄鑰).

However, Suwa Myojin defeated Moreya using a single acacia branch/inda. After his victory, he planted the acacia branch in the ground, which grew into a dense ligule called Fujisuva no mori (藤諏方森).

The Fujisima Shrine (藤島社) or Fujisima (Dai)mjojin (藤島大明神) in Suva City is a side shrine of Suva Kasima, where agricultural ceremonies are traditionally performed every June at the traditional site of the acacia grove.

Although earlier versions of this myth place the battle in the area where the Kamisa still stands today, more modern versions place it instead in the town of Okaja, by the Tenryu River, where two shrines stand on adjacent sides of the river: one is the Fujishima Shrine, now accepted as the place where Suva Myojin first set foot in this region, the other shrine is the Moriya Shrine (洩矢神社) dedicated to Moreya.

While the earliest known evidence of this legend emerges in a petition submitted by the high priest (or ohory) of Kamisa to the Minamoto shogunate in 1249, it claims that Suva Myojin descended from heaven to Suva. Other sources identifying Suva Myojin with Izumoi Takeminakata instead describe the god as having come from that area.

The toad god and the sacred rock perch

Two texts, the Monoimi no rei and the Suva Sitsu (陬波私注 "Personal Records of the Suva Misirusibumin" written between 1313-1314), mention an oral legend about Suva Myojin that he can calm the waves of the four seas by subduing an unruly and barbaric toad-gypsy (蝦蟆神).

After defeating the toad, Suva Myojin blocks the way to its abode - the underground palace of the sea dragon god Ryugu-joo - with a rock and sits on it (御座石 Goza-isi or 石(之)御座 isi no goza - "rock seat").

The story functions as an etymological legend for the frog sacrifice held on the first day of every New Year in Suva Kamisa, as well as another folk origin for the place name Suva, which is derived from a term used to describe a wave that skins the shore of the sea (陬波 namisizuka).

The depiction of Suva Myojin's enemy as a toad, or frog, also refers to the figure of Suva Myojin as an aquatic snake god, as frogs are preyed upon by snakes. (By comparison, the mysterious snake god, Ugajin, was also credited with defeating a hostile frog deity.)

The toad-god himself was interpreted as a representative of the indigenous deities Misaguji and/or Moreya, symbolizing the victory of the Suva Myojin cult over the indigenous belief system, and as the three poisons (ignorance, greed and hatred) in Buddhist understanding.

Which is believed to have been destroyed by Suva Myojin as the incarnation of Samantabhadra bodhisattva, esoteric aspetkusa Vajrasattva and the Wisdom King Trailokyavijaya.

The current whereabouts of Goza-isi are unclear. The Monoimi no rei claims that it was located somewhere within the "Sōmen" (正面之内ニ在リ), i.e., the highlands of the Kamisa Honmiya (上壇 jodan), where the inner shrine itself is located, and believes it to be one of the seven sacred rocks or stones (七石 nana-isi) associated with the shrine.

While three of the seven sacred rocks are indeed located within the Kamisa Honmiya - the Suzuri (硯石), the (O)kucu-isi(御沓石), and the Kaeru-isi (蛙石) or Kabutoisi (甲石) - none are currently referred to as Goza-isi. However, attempts have been made to identify Goza-isi with one of these three rocks.

Hara (2012) speculates that Goza-isi may have been the same rock as Kaeru-isi/Kabuto-isi (its exact location is debated), noting that two sources from the Edo period claim that Kaeru-isi is located under a stone pagoda, which was once identified as lying in the inner sanctuary of the Tetto (鉄塔 "iron tower").

In the Meiji era, before the separation of Buddhism and Shinto, it was believed to be the physical body of the god Suva and the main object of Kamisa worship. Moreover, in the 18th century, the Téteru-u-is was believed to be the main object of worship of the Kamisa.

The 18th-century traveler and ethnologist Masumi Sugae (菅江真澄, 1754-1829[98]) reported that frogs sacrificed during New Year's ceremonies were offered to an ivakura (磐座, a rock throne or sacred rock) at the shrine.

Meanwhile, a map of the Kamisa dated to the Tenso period (1573-1592) shows a rock inscribed with Goza-isi, placed next to the Tenrjúsui-sa (天流水舎), a building with a hole or pipe at the top, which serves to collect the three drops of water that miraculously trickle into it every day regardless of the weather.

According to one author, this means that the Goza-isi was immediately moved to the inner shrine as soon as the Buddhist religion became more firmly established in the shrine and the worship of ivakura became less important. However, at present, no such rock exists next to the structure.

In addition to the Goza-isi Shrine of Kamisa (御座石神社 or Gozanso), there is a rock in the town of Chino in Nagano, which has sometimes been identified with the indeterminate Goza-isi.

Kanai, meanwhile, believed in 1982 that Gozai-isi originally referred to an untempered boulder in the artificial Sirakaba Lake, a former wetland at the foot of Mount Tatesina, beneath which a cave containing ancient clay and stone vessels - Kanai believed these may have been ceremonial wares and suggesting that the area once held religious significance - was discovered when a dam burst drained the lake in 1954.

Travel to Izumo

According to a local folktale, Suva Myojin is one of the few kamis in Japan who do not leave their shrines during the month of Kannazuki (神無月) (Kannazuki is the name of the 10th month in the traditional Japanese calendar; literally meaning "the month when there are no gods"; also called Kaminasizuki), when most deities gather in Izumo province and are notably absent from most of the countryside.

According to folktales, Suva Myojin once came to Izumo in the form of a dragon so huge that only its head was visible, but its tail was still in Suva, hanging on a tall pine tree by a lake. The other gods were so shocked and frightened by its sheer size that they were excused from attending their annual meeting.

The supposed tree where the dragon's tail was caught (now just a stump) is known locally as Okakemacu (尾掛松 ).

A version of this story relocates the abandonment of Izumo to the Imperial Palace in Kyoto. In this version, it is believed that many kami traveled to the ancient capital on the first day of each New Year to greet the emperor.

Omivatari

The cracks and grooves that form on the icy Lake Suva during the cold winter are traditionally interpreted as traces of Suva Myojin, left behind when he leaves Kamisa and crosses the lake to meet his wife, who is also worshipped as a god on the opposite (northern) shore of the lake, at Simosa.

This is called Omivatari (御神渡 "the god's crossing place" or "the god's path"). It is believed that cracks are a good omen for the coming year. The priest of the Great Shrine of Suva traditionally used the appearance of cracks to predict the quality of the annual harvest.

To the locals, cracks were also a sign that they could safely step on frozen ice. Conversely, if the omivatari did not appear at all (明海 ake no umi) or the cracks took an unusual shape, it was believed to be a sign of bad luck for the coming year.

Since the late 20th century, omivatari have become a much less common phenomenon, due to global warming.

Appearance Sakanoue no Tamuramaro before

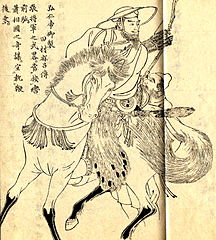

Suwa Myojin's connection to warfare and hunting is best revealed by another legend in which he appears before the warlord Sakanoue no Tamuramaro during a later campaign to subjugate the Emishi of northeastern Japan. The following summary is based on the version found in Ekotoba.

During the reign of Emperor Kanmu, an Emish leader named Abe no Takamaru (安倍高丸) incited a rebellion against the imperial court. In retaliation, the emperor appointed Sakanoue no Tamuramaru, the Taisogun of Sei (head of the imperial armies), and sent him to Oshu to suppress the Emishi threat.

Tamuramaro, knowing that he could not defeat Takamaru without divine help, prayed to Suwa Myojin for victory. As he and his army crossed the Ina and Suwa districts of Sinano province, a warrior on a rough horse - Suwa Myojin in disguise - joined their march.

Arriving at Takamaru's impregnable sea fortress, the Sinano rider miraculously split into five warriors, all identical and equipped with arrows (the mainfestation of Suva Myojin's thirteen heavenly children), while twenty men in yellow robes (attendants of the gods) appeared out of nowhere.

The horsemen and the men in yellow then hold an equestrian contest on the surface of the sea, which successfully lures Takamaru out of hiding. The horseman then blinds Takamaru with his last remaining arrow, so that the twenty men in yellow capture him and behead him, pinning his head on a spear.

On the return journey, the warrior's horse suddenly rose into the sky as the rider assumed the deity's courtly guise He then revealed his true identity to his entourage as the god of Suva and announced his worship of the hunt.

Tamuramaro asked the deity why he took pleasure in such an activity, which involved the extermination of sentient beings. Suva Myojin explained the incident by saying that by hunting them and killing them, he was actually helping the sinful and ignorant animals to attain enlightenment.

He then bequeaths Tamuramaro a written dharani (Sanskrit term for a kind of ritual speech similar to a mantra) - probably a reference to Suva Misirusibumi - and finally disappears. In accordance with Suva Myojin's wishes, Tamuramaro then calls on the court to organise religious ceremonies for the Suvai shrines.

Repulsing the Mongol invasion

Suva Myojin also deserves credit for repelling the Mongols who attempted to invade Japan under Kublai Khan.

The Taiheiki (The Chronicle of the Great Peace) tells a story in which a five-coloured cloud resembling a snake (a manifestation of Suva Myojin) emerges from Lake Suva and dissipates westwards to help the Japanese army against the Mongols. The Ekotoba tells a similar anecdote, in which Suva Myojin appears as a huge dragon riding on a cloud in the summer of 1279.

Takeminakata Analysis

Absence of Takeminakata in other Izumo contexts

The rather unexpected disappearance of Takeminakata in the kuni-yuzuri version of the Kodjiki myth of kuni-yuzuri has long troubled scholars, as the deity is not mentioned anywhere else in the work, including in the genealogy of his descendant Ókuninusi, which predates the kuni-yuzuri narrative in time.

Aside from the parallel narrative included in the Kuji Hongi, Takeminakata's presence is entirely absent from Nihonsoki's version of the myth. Furthermore, early sources from Izumo, such as the province's Fudoki (風土記), do not mention any god called Takeminakata, nor is there any record of such a deity being worshipped in ancient Izumo.

Modern writers such as Motoori Norinaga attempted to explain the absence of Takeminakata's presence outside of the Kodjiki and the Kuji Hong by conflating the deity with other mysterious deities he found in other sources and believed to share certain descriptive traits (such as the shameful deity of Isekuhiko).

While some modern scholars still assume a connection between the deity and Izumo, claiming that Takeminakata's origins lie in the people who migrated northward from Izumo to Suva and the Hokuriku zone or to Hokuriku itself.

A region that was once under the jurisdiction of Izumo, more specifically Ecsigo Province (now Niigata Prefecture). Others, in light of the aforementioned silence, prefer to believe that the connection between Takeminakata and Izumo is merely an artificial construct by the editors of Kodjiki.

The expansion of the Jamato state into Suva

It is said that the Jamato rule penetrated Suva (present-day Kamiina and Simoina districts) from the south sometime in the second half of the 6th century.

The fact that the form of the corridor-type kofun (横穴式石室 jokoana-siki sekisicu) in the region is distinctly different from that of the mounds (said to be the tombs of influential local high priests)

built on the south side of Lake Suva - in the area of Suva Kamisa in the 5th century AD - is a sign that the region's kofun were built in the same way as the kofun of the southern side of Lake Suva. and 6th centuries, and where the tomb is typically surrounded by a moat, must be a sign of the expansion of the Jamato state within the region.

The Kuji Hongi mentions the grandson or descendant of Kamujaimimi-no-Mikoto (son of Emperor Jinmu), Takeiotacu-no-Mikoto, who was appointed governor of Sinano (kuni no mijacuko; 科野国造) during the reign of Emperor Sujin (traditionally in the 1st century BC). century BC, but most likely sometime around the 4th century AD).

The Ihon Aso-si keizu claims, with disputed historical authenticity, that Takeiotacu was a descendant of the Kinmei emperor Kanejumi-no-kimi (金弓君) (reign: 539-571), while serving as a toneri (舎人, servant or palace guard) in his palace - Kanasasi-no-miya (金刺宮), now Sakurai in Nara Prefecture - earned the title of atai kabane (直) from the said emperor.

One of Kanejumi's sons, Masze-no-kimi (麻背君), who became kuni no miyakuko of Sinano Province, had two sons. Kuratari, the first son (倉足), was appointed administrator (kóri no kami/hjótoku) of Suwa district (諏訪評督), while Otoei or Kumako, the second son, became a priest or ohóri of the Suwa god (諏訪大神大祝)

The subversion of power

It is said that the Suva region was originally inhabited by autonomous village communities during the late Jajoi period. Chiefs also took on the role of ceremonial leaders at the head of their own communities. The villages were eventually unified under a single leader who directed the religious practices of these communities.

The practices centred around the worship of the god or gods or spirits of Misaguji. Spirits that would descend and take up residence in natural objects, including trees or rocks, and then continue to act as life-giving guardians in local communities.

The legend of the battle between the god Moreja and the Mijojin of Suva may suggest that the coming of Jamato rule to Suva in the late 6th century AD initially met with resistance, especially on the southern side of Lake Suva, which was a bastion of the indigenous cult of Misaguji.

This intransigence was eventually quelled and politico-religious governance over the region was soon seized by descendants of priestly leaders who later became known as the Morija family (守矢氏), the power appointed by the Yamatos.

It was at about this time that the shamanistic concept of the Mizogi-Hori/Ahori shamanism, the physical manifestation of an invisible deity, came into being to encompass indigenous religious practices in the Jamato belief system.

The Ohori vocation probably had to rival that of Oko (神使), a young boy (or boys) who filled the role of the earthly body of Misaguji during religious ceremonies and who were later interpreted as representatives of Ohori.

In the meantime, the priestly chief of the Morija family had been integrated into the new system as kan no osa/jinzo (神長) or jinzokan (神長官), the only priest who could address Misaguji.

By submitting and cooperating with the new regime, the Morija family allowed the local cult of Misaguji to survive under it. While (the Misaguji) was officially subordinate to the Ohori, in reality the Morija jinchokan, who presided over the religious ceremonies, continued to exercise power and the Ohori was only a symbolic leader.

The Ohori's initiation ceremony even involved the jinchokan invoking the spirit of Misaguji to enter the young candidate's body during the ceremony. Only when the candidate himself was in possession of Misaguji's body could he become a god.

The ascension of Takeminakata

Both the Aso and the Suva genealogies refer to the foundations of a shrine (社壇) on the southern shore of Lake Suva (where the present Suva Kamisa stands), where other deities were worshipped along with the mighty god of Suva (諏訪大神), in the 3rd month of the 2nd year of the reign of Emperor Yomei (587 AD). These two sources refer to Ototei/Kumakora as the first Ochorians.

In 691 AD, the Nihonsoki refers to envoys from the Jamato court who came to Sinano Province to "worship the gods of Minochi and Suva" (須波水内等神). This reference may suggest that the cult and shrine of the Old Hori of Suva became so accepted and influential that it attracted the attention of the Jamato imperial court.

Less than 20 years after this, the name "(Take)minakata(tomi)" - which may have been originally derived from the name Ohorian - appears in a historical record, and for the first time in the Kodjiki (711-712 AD).

Due to the absence of Takeminakata, other sources on Izumo believe that the god was interpolated into the text of the Kodjiki by the editor of the Kodjiki himself, Oh no Yasumaro, who either reworked a pre-existing myth or created a completely new one.

Scholars believe that several factors played a role in the appearance of Takeminakata according to the Kodjiki narrative - one of them being that Yasumaro's family, the Ó (太氏; also spelled 多, 意富, or 於保), was distantly related to the family, namely the Kanasasi no-toneri, that ruled the Suva region (金刺舎人).

In this case, it is assumed that both tribes may have been descendants of the Kamujaimimi-no-Mikoto. Thus, by including Takeminakata in the Kodjiki, it was a way of proclaiming the new god of Kanasasi.

Another possible reason was the extraordinary interest shown by Emperor Tenmu (the Tenmu emperor who ordered the Kodjiki and Nihonsoki to be made) in Sinano. The Nihonsoki speaks of Tenmu, in the 13th year of his reign, sending envoys to investigate the area, "perhaps with the purpose of founding a capital."

While the Kodjiki does not mention in detail the worship of Takeminata at Suva, we can see the name applied to the god worshipped at what is now known as the Great Shrine of Suva for the next century. In 842 A.D., the Imperial Court promoted him to the rank of junior 5 (従五位下).

Between 850 and 860, Takeminakata and his shrine rose very rapidly in rank by being granted the superior grade of junior 5 (従五位上) in 850, 851, junior 3 (従三位), 859, junior (従二位), then senoir 2 (正二位), and finally junior 1 in 867 (従一位). It was believed that the influence of the Kanasasi-no-toneri family was behind the deity's sudden rise in rank.

A few decades later, the Engisiki (927) "Nomenclature of Deities" (神名帳 Jinmjōcho) chapter speaks of the Minakatatomi Shrines (南方刀美神社), where two deities were worshipped and which proved to be the two prominent shrines of the Suva district. By 940 the deity was promoted to the highest rank, senior 1 (正一位).

Takeminakata and Suva Myojin

While the above sources (edited by the imperial court in Heian-kyo, which is now Kyoto) use the name (Take)minakata for the god of the Great Shrine of Suva, the god was never worshipped or referred to by that name within Suva.

It is a testament to the enduring influence of the pre-Jamat belief system of Misaguji that many of the religious ceremonies of the Suva Kamisa and the surviving descriptions of other rituals mentioned characterize Misaguji as the center of belief rather than Takeminakata, who does not appear in these liturgies at all.

Even local stories characterizing the deity of Suva Kamisa have been recorded in medieval texts referring to the deity in question with general terms such as sonsin (尊神 'revered deity') or myojin (明神 'manifest deity').

The character portrayal of Takeminakata in the Kodjiki and the Kuji Hongi as having suffered a humiliating defeat was apparently considered embarrassing during the Middle Ages, leading to the appearance of alternative stories that cast the origins of Suva Myojin in a more positive light, such as the legend of Koga Szaburo.

The earliest documents from the territory of Suva that explicitly name Suva Myojin as Takeminakata or identify him with the god Izumo are the Monoimi no rei (1238) - which mentions in passing that Suva Myojin's name is Takeminakata Myojin (武御名方明神)- and the Suva Daimyo Jin Ekotoba (1356).

The latter creatively retells the legend of Izumo kuni-juzuri, found in the Kuji Hongi', by omitting any reference to his defeat.

The popularity of Ekotoba among a wide audience, including the clergy of the Great Shrine of Suva, seems to have helped to finally solidify the identity of Suva Myojin with Takeminakata, supported by the story of his being the son of Ókuninus who came to Suva from Izumo.

Takeminakata Spouse and descendants

Yasakatome

The consort of Suva Myojin is the goddess Yasakatome-no-Kami (八坂刀売神), who is most often regarded as the deity of the Lower Suva Shrine or Simosa. Unlike the relatively well-documented Suva Kamisa, little concrete information is available regarding the origin of Simosa and its goddess.[176]

The first authoritative historical source on Yasakatome is found in the Soku Nihon Kōki, where the goddess is granted the junior rank of 5 (従五位下) by the imperial court in the 9th century Heian period. (842 AD), five months after the same rank was bestowed upon Takeminakata.

As Takeminakata rose in rank, so did Yasakatome. Thus, by 867 AD, Yasakatome was promoted to the rank of Senior 2 (正二位). The goddess was finally promoted to the rank of Senior 1 (正一位) in 1074.

The stories and claims about the goddess are all varied and contradictory. For example, regarding her ancestry, the Kavaai Shrine (川会神社) tana in Kitaazumi district identifies Yasakatomi with Vatacumi, the sea goddess, which is thought to suggest a connection between the goddess and the seafaring Azumi (安曇氏) family.

Another claim from Edo-period sources is that Yasakatome was the daughter of the god Ame-no-Yasakahiko (天八坂彦命), whom the Kuji Hongi records as a companion of Nigihajahi-no-Mikoto at the time the latter descended from heaven.

The cracks that appear on the icy surface of Lake Suva during cold winters - also known as omivatari - have gained fame in folklore for being caused by Suva Myojin crossing the frozen lake with the intention of visiting Yasakatomi.

Princess Kasuga

The legend of Kōga Szaburo identifies the goddess Simosa with the consort of Szaburo, whose name is given in some versions of the story as Princess Kaszuga (春日姫 Kaszuga-hime).

Takeminakata Children

In Suva, many local deities are popularly thought of as the children of Suva Myodzin and his consort. Óta lists the following deities (1926):

- Hikokamivake-no-Mikoto (彦神別命)

- Tacuvakahime-no-Kami (多都若姫神)

- Taruhime-no-Kami (多留姫神)

- Izuhajao-no-Mikoto (伊豆早雄命)

- Tatesina-no-Kami (建志名神)

- Cumasinahime-no-Kami (妻科姫神)

- Ikeno'o-no-Kami (池生神)

- Cumajamizuhime-no-Mikoto (都麻屋美豆姫命)

- Jakine-no-Mikoto (八杵命)

- Szuva-vakahiko-no-Mikoto (洲羽若彦命)

- Katakurabe-no-Mikoto (片倉辺命)

- Okihagi-no-Mikoto (興波岐命)

- Vakemizuhiko-no-Mikoto (別水彦命)

- Moritacu-no-Kami (守達神)

- Takamori-no-kami (高杜神)

- Enatakemimi-no-Mikoto (恵奈武耳命)

- Okucuivatate-no-Kami (奥津石建神)

- Ohocuno-no-Kami (竟富角神)

- Ókunugi-no-Kami (大橡神)

Presumed descendants

Suva family

The Suwa family, who once held the position of high priest or Ohoro of the Suwa Kamisa, traditionally considered themselves descendants of Suwa Myojin/Takeminakata.

Although historically they may have been descendants of the Kanasasi-o-toneri family, appointed by the Jamato court in the 6th century to govern the Suva area.

Other families

The Ohori of Suva were assisted by five priests, some of whom were regarded as descendants of local deities associated with the Myojin/Takeminakata of Suva.

One family, the Koide (小出氏), who were the original holders of the negi-dajú (禰宜大夫) and gi-no-hóri (擬祝) offices, claimed to be descended from the god Yakine. A second family, the Jajima (八島(嶋)氏 or 矢島氏), which served as gon-no-hori (権祝), regarded the god Ikeno'o as their ancestor.

Takeminakata Worship

Shrines

As the deity of the Great Shrine of Suva, Suva Myojin/Takeminakata and Yasakatome are also deities of the shrines that belong to the Suva Shrine Network (諏訪神社 Suva Jinja) throughout Japan.

As the god of wind and water

The Nihonsoki record that Jamato's envoys, in addition to the god Suva, also worshipped the gods of the Tacuta Shrine - revered for their power to control and avert wind-related disasters such as droughts and typhoons - suggests that the Jamato imperial court recognized the deity as the god of wind and water in the late 7th century AD.

One theory concerning the origin of the name (Take)minakata even suggests that the name derives from the word for "body of water" (水潟 minakata).

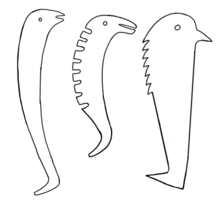

Iron blades made of snake-shaped iron called nagikama (薙鎌) were traditionally used in the Suva region to ward off strong winds, typhoons and other natural disasters.

It was once customary to attach the nagikama to the end of a wooden pole and place it on a corner of the roof during autumn typhoons. It was even traditional to place nagikama on trees selected for the onbasira of the Kamisa and Simosa of Suva, some time before they were cut down.

In addition to these and other uses, the blades were also used as sintai (sacred body of the god) for the branches of the Suva shrine network.

Relations with snakes and dragons

Suva Myojin's relationship with the serpent/dragon may stem from the fact that in many stories in which he appears, such as the legend of Koga Saburo, he is regarded as a deity who rules over wind and water. Hence the connection with dragons, which are associated with wind and rain in Japanese lore.

During the syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism

During the medieval period, during the later merger of Buddhism and Shinto, Suva Myojin was identified with Samantabhadra bodhisattva (Fugen Bosacu), and the goddess Simosa was associated with the thousand-armed figure of Avalokiteshvara (Senzu Kannon) bodhisattva.

During the same period, Buddhist temples and other structures were erected in the immediate vicinity of both shrines, including a stone pagoda, the Tetto (鉄塔 "iron tower"). This symbolises the legendary iron tower of India, where, according to Singon tradition, Nagarjuna received esoteric teachings from Vajrasattva (sometimes identified with Samantabhadra).

And they even built a shrine to Samantabhadra (普賢堂 Fugendo). Both this stone pagoda and the shrine served as the main object of worship at Kamisa.

With the institution of the Shinto, after the Meiji Restoration in 1868 and the subsequent separation of Buddhism and the Shinto, the shrine monks (saso - priest belonging to one shrine) who belonged to the Buddhist temples in the Suva shrine complex were secularized and with them the Buddhist symbols and buildings were removed or destroyed.

Buddhist ceremonies performed in both the Kamisa and Simosa, such as the annual Lotus Sutra offering to Suva Myojin (which included the placement of a copy of the sutra in the Tetto) were abolished.

As the god of hunting

Suva Myojin was also worshipped as the god of hunting, so not surprisingly some of the Kamisa's religious ceremonies traditionally included a hunting ritual and/or animal sacrifice.

One such ritual is the Frog Hunting Ceremony (蛙狩神事 kavazugari sindji), which is held on the first day of every new year. The ritual involves shooting (or rather piercing) frogs with small arrows from a sacred river or stream in the immediate vicinity of Kamisa.

This ritual, which has come under sharp criticism from local activists and animal rights organizations for the perceived cruelty meted out to the frogs, was traditionally performed to ensure peace and abundant harvests for the following year.

During another festival, Ontōsai (御頭祭) or Tori no macuri (酉の祭, so called because it used to be held on Rooster Day), currently held on 15 April, seventy-five stuffed deer heads (in the past, freshly slaughtered deer heads were used for this purpose) are offered as well,

as well as the consumption of venison and other game, such as wild boar or rabbit, and various types of seafood and other foods prepared by both priests and participants in a ceremonial feast.

One of the hunting festivals of the Suva Kamisa, the Misaima Festival used to be held in a field (koya - 神野 'the plain of the god') - at the foot of Mount Jacugatake and lasted for five days (from the twenty-sixth day of July/seventh month to the thirtieth).

During the Kamakura era, it was the most prominent of the Suwa festivals, attracting members of many samurai orders from all over Japan who participated in horseback riding, sumo wrestling and solo wrestling as part of the celebration; and members of all sorts of other orders.

The Simosa also held their own Mizajama Festival at the same time as the Kamisai (albeit at a different location), with many warrior tribes participating.

Suva Myojin's connection with the mountains and hunting is also undeniable from the description of him sitting on a deer deer (it was believed that for Suva Myojin, the deer was a sacred animal) during the Ontosa ceremony, as it was performed during the Middle Ages.

Suva Myojin and meat-eating

At a time when the slaughter of animals and the consumption of meat were frowned upon because of Mahayana Buddhism's strict views on vegetarianism and the pervasive Buddhist ethic against the extinction of life, the cult of Suva Myojin was unique in Japanese religious life in celebrating hunting and meat-eating.

A 4-line poem was appended to the legend of Koga Szaburo, commonly known as the Suva no kanmont (諏訪の勘文), which expresses the essence of the rightness of eating meat within the Buddhist framework. Ignorant animals can attain enlightenment by being consumed by humans and then "living" in their bodies along with their human consumers.

"業尽有情 Gojin Ujo

雖放不生 Suiho fuso

故宿人天 Kosuku ninten

同証仏果 Dósó bukka"

Sensitive beings who have exhausted their destiny:

Even if one is released, it will not live long;

So let them live in men and gods

And then may they attain to Buddhahood

The Kamisa made special talismans (鹿食免 kadjiki-men "permission to eat deer meat") and chopsticks (鹿食箸 kadjiki-basi) that empowered their owners to eat meat. Since these were rare talismans throughout Japan, they became very popular among hunters and meat-eaters.

Kamisa priests and itinerant preachers who were associated with the shrine known as oshi (御師) also distributed these sacred licenses and chopsticks to the public. They spread the tale of Suva Myojin and other stories of the deity's good deeds.

Per military

Suva Myojin is also regarded as the god of war, one of several similar deities in the Japanese pantheon.

In addition to the legend of the deity's appearance to Sakanoue no Tamuramaro , the Ryojin Hiso, at the time of its compilation in 1179 (late Heian period), also attests to the worship of the deity Suva as the god of warfare, naming Suva's shrine among the shrines of famous war gods that stood in the eastern half of the country.

"These war gods live on the eastern side of the border:

Kasima, Katori, Suva no Miyas and Hira Myojin;

Suva in Ava, Otaka Myojin in Tai no Kuchi,

Jacurugi Acuta and Tado no Mija Ise."

Song 258 of the Ryojin Hiso

(During the Heian period, the term "eastern border" (関の東 szeki-no-hi(n)gasi, from which the term 関東 Kantō derives) referred to the provinces beyond the checkpoints or border posts on the eastern edge of the main region,

specifically the land east of the checkpoint at Mount Osaka/Ausaka (逢坂 'the mountain of the meeting', old spelling: Afusaka; not to be confused with the modern city of Osaka), which is the same as the present-day Ozu in Siga Prefecture. By the Edo period, the term Kantō had been reinterpreted to mean the region east of the checkpoint in Hakone, Kanagava Prefecture.)

During the Kamakura era, the relationship of the Suwa family with the shogunate and the Hojō family helped to consolidate the veneration of Suwa Myojin as a war god. Suwa's shrines and priestly tribe enjoyed a heyday under the patronage of the Hojō, who worshipped the deity with devotion as a sign of their loyalty to the shogunate.

Numerous branches of Suva shrines developed throughout Japan, especially in areas where families were devoted to worshipping Suva Myojin (for example, the Kanto region, which was the traditional bastion of the Minamoto family (Seiva Gendji - branch of Seiva).

The Takeda family in Kai Province (present-day Yamasa Prefecture) were devotees of Suva Myojin, and their most famous member, the Sengoku Takeda Shingen daimyo, was no exception.

His devotion can be seen in some of his war banners, which were decorated with the deity's name and inscriptions, such as the Namu Darma-Natured Suva Nangu Hosho Kamisimo Daimyo Jin (南無諏方南宮法性上下大明神) from the lower and upper shrines of Suva.

The iconic horned helmet with the falling white hair is usually associated with Singen, popularly known as the Suva-hosso helmet (諏訪法性兜 Suva-hosso(no)-kabuto) is famous for being blessed by the deity, guaranteeing a successful battle for the wearer. Singen even issued a law in 1565 to restore the religious ceremonies of the Kamisa and Simosa.

Takeminakata and sumo wrestling

Takeminakata and Takemikazuichi's fight in Kodjiki has been interpreted as the origin myth of sumo wrestling.

Sumo was first documented in Suva itself during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods, and before it became widespread among the general population as a form of entertainment it was performed as a religious ritual during festivals.

Takeminakata In mass culture

- In the Japanese version of the video game series Samurai Warriors, one of Sakon Sima's weapons is called Takeminakata (猛壬那刀).

- In the video game series Sin Megami Tensei, Take-Minakata (タケミナカタ) is portrayed as a demon.

- The development team of Team Shanghai Alice used both Yasakatome and Suwa Myojin as the basis for the "main villain" in the final stage of their video game Mountain of Faith (part of the Toho draft). There is also a secondary villain, Moriya Suvako, for whom Moreya is based. Fan-made emas (vow images) bearing the likenesses of these characters have become common at shrines associated with both Moreya and Takeminakata, and have therefore become popular pilgrimage sites among Tóho fans.