Seppuku

Share

Seppuku (切腹 lit. "to cut the belly"), commonly known in the West as haraquiri or haraquiri (腹切 or 腹切り), refers to a Japanese suicide ritual reserved for the warrior class, mainly samurai, in which suicide by disembowelment occurs.

It appeared in Japan in the mid-12th century becoming widespread until 1868, when its practice was officially banned. The word haraquiri, although widely known abroad, is rarely used by the Japanese, who prefer the term seppuku (composed of the same Chinese characters in reverse order).

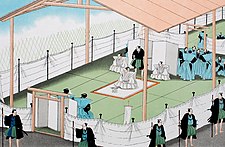

The disemboweling ritual was usually part of a very elaborate ceremony performed in front of spectators.

The proper method of execution consisted of a horizontal cut (kiru) in the area of the abdomen, below the navel (hara), made with a tantō, wakizashi or a simple dagger, starting from the left side and cutting all the way to the right side, thus leaving the viscera exposed as a way of showing purity of character.

Finally, if the forces allowed it, another cut was made by pulling the blade upwards, prolonging the first cut or starting a new one in the middle of it. When the cut was finished, the kaishakunin (介错人) performed his main function in the ritual, the beheading.

Being an extremely slow and painful process of suicide, seppuku was used as a method of demonstrating the courage, self-control and strong determination characteristic of a samurai.

As part of the bushido code of honor, seppuku was a common practice among samurai, who considered their lives as a surrender to the honor of dying gloriously, rejecting to fall into the hands of their enemies, or as a form of death penalty in the face of dishonor for a crime, misdemeanor, or otherwise ignominizing them.

Other reasons were behind these courageous acts, such as breaking the law or the so-called oibara (追腹), in which the rōnin (浪人 lit. "wave man") after losing his daimyo (大名 lit. "great name"), who at the time held a similar role to the feudal lord in the West, would be compelled to practice seppuku, except in cases where his lord in writing prevented such a custom.

Seppuku Vocabulary and etymology

The words haraquiri (腹切り "belly" + "cut") and seppuku (切腹) are written with the same kanji characters; however in reverse order and with different readings: haraquiri uses the kun reading (of Japanese origin) - in addition to the additional okurigana り - and seppuku the on reading (of Chinese origin).

" As a rule haraquiri is considered a term of ordinary usage, but this is a mistake. Haraquiri is the Japanese reading of characters in kun'yomi; and since it has become common to prefer the Chinese reading in official documents, only the term seppuku is used in writing. Thus, haraquiri is the oral term and seppuku the written term designating a single act. "

- Christopher Ross, Mishima's Sword, p.68.

The word jigai (自害) means "suicide" in Japanese and the word currently used for "suicide" is jisatsu (自殺). Related words include jiketsu (自决) and jijin (自尽). In some popular Western texts, such as martial arts magazines, the term is associated with suicide practiced by samurai wives.

Seppuku Overview

By all accounts, the earliest account of seppuku dates back to the 11th century, when clans of powerful families fought for supremacy during the shogunate period.However, the habit of battlefield suicide performed to avoid capture by enemy forces is much older.

The first haraquiri cited in the war chronicles dates back to 1170, committed by the notorious Minamoto no Tametomo of the Minamoto clan, known for his archery skills, who commits suicide after losing a battle against the Taira clan.

The first formal model of the seppuku ritual, on the other hand, was that of Minamoto no Yorimasa in 1180, motivated by an inevitable defeat at the First Battle of Uji in 1180 and executed at the temple of Byōdō-in.

Already among the best known and most horrific stories of haraquiri committed by a samurai warrior occurred in 1333, in the Kenmu era, when Murakami Yoshiteru gutted himself to conceal the escape of his lord[b] during the war for the restoration of full imperial powers, in opposition to the bushidan of the Hojo clan - who ruled in the Kamakura shogunate at the time.

Prior to the introduction of Buddhism in Japan, the history of the country reveals that the Japanese people would tend to emphasize the continuity of life while the Zen tradition tends to stress the importance of the moment and the manner of dying. The important thing becomes not only whether the body lives and dies, but whether the mind lives in harmony and peace with itself.

The Japanese placed more importance on the peace of mind and the honor of life than a long life. With the acceptance of Buddhism and its respective concepts of the transitoriness of the nature of life and the glory of death, the development of the thought of this type of ritual became possible.

Unlike the Christian religions, both Buddhism and Shintoism do not carry the stigma of sin attached to the act of suicide. Thus, suicide came to be seen as a good way to resolve certain situations, not being considered an act of despair, but rather one of rigorous self-denial and lucidity.

The willpower required for the withdrawal of one's life expressed pride, fighting back the supposed outrage and warding off failure. Death may even be regrettable, but suicide is different; the suicide kills himself, fascinating those who are left with his ability to lend himself to voluntary death for noble reasons such as love, honor, or patriotism.

The noble nature of suicide was born in Japanese antiquity. The burials of the chiefs of the early clans took place alongside the compulsory burial of their relatives; a custom that was also common in China and India.

The practice, called shinjū, lasted until the 5th century, when the death of relatives was replaced by the keeping of terracotta statues, although voluntary accompaniment in death was maintained. Ceremonial suicide became of great importance to the Japanese people.

By overcoming the fear of death, the samurai overcame the great riddle of humanity, setting themselves apart from the other classes existing at the time. For a samurai, the loss of honor was unacceptable. Taking one's own life was preferable to living under any shame. On the battlefield, suicide demonstrated that the warrior had fought bravely and deserved an honorable death.

After the Meiji Restoration, the central government established a series of prohibitions regarding samurai in order to prevent a power grab by shoguns, so seppuku was officially abolished in 1873 as a form of punishment.

However, this type of practice continued to exist voluntarily. One of the best known cases involved several military officers and civilians committing the act in 1945, when Japan is defeated at the end of World War II.

Among other notable cases is that of writer Yukio Mishima who, in 1970, disrobed in protest at the Japanese army's inertia regarding his proposed coup d'état to return power to the emperor.

Seppuku History

Having analyzed the culture of suicide in Japan, let us emphasize this practice among the warrior aristocracy with special attention to the ideology of sacrifice that arose in Imperial Japan, because an entire continuation derived from the samurai tradition was structured from it.

The samurai method of suicide was forbidden to members of other social strata, and even in the core of samurai families, only the men were entitled to the haraquiri. Women were reserved for jigai, in which they cut their necks with a dagger.

In the scope of samurai practices in battle - present since the 12th century and still current during the battle of Sekigahara, at the threshold of the Tokugawa pax - the defeated were at the mercy of their enemies (in particular vassals).

Such ruthlessness towards defeated opponents was mainly due to the "head inspection" ritual in which a daimyo or general examined the severed heads of defeated enemies, killed during or after combat.

After these heads were washed, combed, perfumed, and presented on boards with tags bearing the dead man's identification, rewards were given to the warriors responsible for the captured heads, rewards that could be in gold or honorific titles.

To account for the value of the reward, not only the number of heads captured was considered, but also the status of the enemies killed. The fact that samurai were subjected to terribly painful deaths at the hands of their captors is one factor that explains this form of suicide, thus robbing the enemy of the triumph of his head and escaping worse humiliation.

As this practice spread and became institutionalized it gained new motivations and assimilated values it did not previously possess. A significant variety of other names for seppuku emerged;

Among the most common were kanshi (protest seppuku), funshi (spite seppuku), munembara (revenge seppuku), oyako shinjū (parent-child suicide), sokotsuki (expiatory seppuku, for negligence), the oibara (accompanying seppuku), and the tsumebara (seppuku as a form of punishment - capital punishment)

- the last three types as the most frequent practice and standing out as major representatives of the samurai tradition. If honor is the central moral value related to the culture, these suicides can be classified as altruistic.

Samurai suicide took on the body of moral motivations, such as protesting injustices or resulting from the inappropriate behavior of some masters, humiliations suffered, defiance against another, testimony of loyalty, atonement for faults and failures, and atonement for crimes committed.

The discipline, loyalty, and mastery of samurai warriors stood out as their main qualities. In fact, loyalty (giri) is the element most dear to the warrior caste, the central substance through which all the demands of Japanese society are inscribed. "The giri was then a cherished face-to-face relationship, with all the feudal trappings.

'Knowing your giri' meant being faithful all one's life to a lord who in turn looked after his dependents. 'Paying one's giri' meant offering even one's own life to the lord to whom one owed everything."

Due to these psychological characters of Japanese society, it was permanently predisposed to suicidal practice, even relying on the clear environment conducive to the expansion of such effects by death, offered by the advent of the shogunate and especially after the rise of the samurai code of ethics, the bushido.

Oibara

The samurai warrior, like the European knight, acted in obedience to his lord or king. However, and unlike in the West where above his lord there was a supreme authority - God - the samurai did not recognize any other authority above his lord.

The emperor himself, although of divine descent, did not interfere in worldly affairs, so that the imperial power over the samurai class was, in practice, almost nil. Note, therefore, that divine faith did not interfere with the samurai's rigid system of loyalty to their lord.

And so it was that the dishonorable death of a feudal lord at the hands of an enemy would not infrequently entail the ritual suicide oibara (追い腹) of all the samurai in his service.

The oibara, or seppuku by accompaniment - which gains the name of junshi, when performed the suicide of the slave on the occasion of the death of his master without, however, being by way of seppuku - would have originated from a practice prior to the institution of the Shogunate.

There, it would be customary for relatives and vassals of great nobles (including the emperor) to be strangled and buried along with the head of the clan.

Regarded as proof of absolute loyalty to their lord, samurai warriors were soon influenced by such a practice of courtly nobility, making it recurrent and accepted (though not universally approved) until the first decades of the Tokugawa Shogunate - see the case of the 47 rōnin.

This collective seppuku could gather up to about 500 warriors, leaving the clans speared and completely defenseless. Tokugawa Ieyasu, who founded Japan's last great shogunate dynasty, finally issued an edict in 1603 that forbade seppuku to primary and secondary serfs. After Tokugawa Ieyasu's death, the vassals of his clan were barred from such a practice.

So entrenched was such a practice in the Japanese aristocracy, cases of suicide by escorting continued to arise and therefore, in May 1663, at the request of Nobutsuna Matsudaira of Izu, the Shogunate government issued a new edict to put an end to this practice that led to an unbelievable loss of human life.

The edict decreed severe punishment for the family of anyone who committed junshi: as had happened to Uyemon no Higoge, whose family had its possessions confiscated and two of its members executed, while others were exiled. Eventually the vassals abandoned this custom and started on the path to becoming Buddhist monks.

Still, there continued to be several cases of disobedience throughout the long Tokugawa reign, and they were even more vigorously welcomed by the population as acts of greater bravery.

One case of disobedience that had become well known was that of General Nogi Maresuke, who committed suicide along with his wife Shizuko shortly after Emperor Meiji's funeral procession left his palace in 1912.

As a result of this ban on the practice of suicide by escort throughout the Empire, even if it was a proof of loyalty (a staggering virtue at the time) its abolition was imposed precisely in a period in which loyalty to one's master was indeed recognized.

Tsumebara

The tsumebara, a very elaborate ritual performed as a form of punishment, consisted of forced evisceration as a death penalty for the samurai. A creation of social order established by the Tokugawa, it gave the samurai primacy over other social statuses.

By law, a right called kiri sute gomen gave a samurai the power to eliminate with his sword anyone of the lower castes who did not respect him. Thus, they had been given the authority to kill members of the commoners without any need for justification, making them the main enforcers of order, authorized and instructed to punish with ruthless violence those who inflicted it.

On the other hand, the samurai had the duty to direct the same punitive act against themselves if they broke the law, this practice also serving to legitimize the samurai's authority in the eyes of the commoners, since the samurai's severity "would have been odious if he himself had not been the first victim.

Since he considered himself the soldier of good, he had to prove incessantly that he did not spare himself. And the more he showed himself cruel to himself, the more he knew they would approve of him."-Pinguet, 1987.

Seppuku as a death penalty was also a characteristic of social inequality in the society of the Tokugawa period. The sentence handed down to the commoner took on other methods of ordered corporal punishment, in which the condemned were exposed to humiliation and punishment;

For example, the pillory, the stigmatizing tattoo, whipping and banishment, and, among the death penalties, beheading, burning, crucifixion (a practice adopted with the arrival of Christian missionaries, which soon became the most widespread means of execution), and nokogiribiki (the practice of burying the person still alive, keeping his neck and head out, leaving beside him two bamboo saws that anyone was allowed to use to saw the condemned);

tsumebara being, a torture which, while not normally regarded as a heroic act (such as the form it took in the case of the 47 rōnin), was at least a way of inflicting punishment on the samurai (self-punishing) while keeping his dignity intact.

Although the bushi only had the right to be executed by beheading - zanai - public execution was considered the disgrace of the samurai. The convicted criminal would be exposed in public through the streets to the usual place of execution, with signs announcing his crime.

This ignominious form of public display was utterly despicable and rejected by the bushi, who carefully strove to maintain a distance between himself and the people.

Only the samurai adjusted to such a condition could be sentenced to commit seppuku as a form of punishment for a crime, meaning that the rōnin who, despite having been born a bushi, upon seeing the termination of his dignified status as a samurai, would no longer be in the service of a feudal lord, and was technically excluded from such an honor.

Exceptions to the rule have however been accounted for throughout history, such as what occurred in the Akō Incident. Capital punishment for tsumebara was suspended from the Japanese penal code only in the year 1873, a few years after the Meiji Restoration.

However, even after the demise of feudalism that would lead to the end of the samurai caste and the proscription by law of tsumebara, the practical disappearance of the other variants of seppuku did not take place. Its too inveterate character in society contained it, and it would not be by a mere and rapid change of political order that seppuku disappeared.

In the 20th century, the construction of the idea of the "nation of samurai", also motivated by the system of compulsory military service, would cause the practice of seppuku to take over Japan in the most varied forms and gaining adepts from all social origins.

It is in this new scenario that kanshi (suicide by protest), one of the forms previously considered marginal to the practice of seppuku, would reach its position as the most recurrent practice of suicide by disembowelment. With the establishment of democracy, political protests arise for a variety of positions.

Suicide takes place mainly by radical militarists who resorted to this act if their convictions were hindered. Suicides after a political assassination were common among Gen'Yosha, Kokuryūkai, and other smaller nationalist groups.

Seppuku Ritual

The seppuku, when performed in the tranquility of the Japanese warrior's castle or residence, was a very elaborate ritual that evoked the enormous rationality of the act. For the ceremony, the samurai bathed to purify his body and soul.

Then he would dress in a specific seppuku outfit, white in color, a symbol of purity and mourning for the Orientals (which would come to light with the gutting of the abdomen). Kneeling in a position called seiza on a white or red felt mat, the warrior prepared to end his life.

In front of him, it was customary to find a small wooden table (sanbo) with a wakizashi or a tantō, wrapped in several sheets of washi paper to provide a better grip. Since it was not always possible to ensure a quick death by means of the complex cuts performed, the help of another person in performing this act became a custom.

On his left side, a person of extreme trust and familiarity, a comrade-in-arms, a friend from the same battalion or a lower class (when not an official designated by the authorities), called a kaishakunin (介錯人), acted as the suicide samurai's assistant, administering the coup de grace.

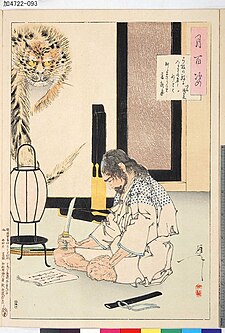

After a brief pronouncement or declamation of a death poem (zeppitsu meaning "last stroke" or yuigon literally meaning "statement left behind")-usually in the form of a haiku, in which the samurai composed his pre-death instants, summarizing his thoughts and emotions at that moment - the warrior would hand the declaration to the witness and take a bowl of sake or water which, by tradition, he would drink in four sips spaced apart.

This action is called shi-mu (where "shi" means "four" and "mu" means "death"), four deaths, as a symbolic reference to the four elements that henceforth he can no longer feel or contemplate: earth, water, wind, and fire.

Next, and after fastening the sleeves of the kimono under his knees in order to allow the fall to take place forward (preventing a fall backwards or sideways, considered undignified positions) he would take the weapon in his hands, draw it and insert the tip of the blade into his belly.

The horizontal cut (kiru) was made in the area of the abdomen, below the navel (hara) with a tantō or wakizashi, starting from the left side and cutting it all the way to the right side, thus leaving the viscera exposed as a way of showing purity of character.

Finally, if forces permitted, another cut was made by pulling the blade upwards, extending the first cut or starting a new one in the middle of the first (jumonji-giri). It was important for the cut to be in the abdomen, the place where Eastern beliefs believe to be the center of reason and emotion.

Thus, the samurai would literally be cutting off his "soul" (see seika tanden). As the samurai quieted his mind and prepared to die in peace, the kaishakunin stood by his side preparing for his main function in the ritual, the beheading.

Any interaction and conversation surrounding an officially ordered seppuku were fixed by tradition, and if the samurai addressed the kaishakunin before or during the ceremony, the standard response would be "go anshin" (keep your mind at peace).

Being an extremely slow and painful process of suicide, the kaishakunin could perform the act of decapitation (kaishaku) before the samurai showed signs of weakness, by exhausting his strength which prevented him from finishing the cut by himself.

The cut was performed with a machete or, though rarely, a tachi, in the cervical region and consisted of a partial or total severing of the neck, causing immediate death. The execution maneuver was usually performed in the modes of daki-kubi (抱き首). Considering the enormous precision required for such a maneuver, the seppuku attendant was supposed to be a skilled swordsman.

Thus, it would be considered immensely disrespectful if the samurai's head was completely beheaded in front of the samurai's relatives, who usually also attended the execution. With the head being suspended in front and held to the neck, the samurai's hidden face represented the great talent of the kaishakunin, and completely removed the stigma of decapitation.

The technical precision of the kaishaku was considered of extreme importance, for the correct execution of the cut was due to the talent of an excellent swordsman, whose performance did not allow any kind of failure.

Despite the presence of the kaishakunin who executed the coup de grâce, this action is still characterized as suicide, since a wound of this type made by such a blade is always fatal, although the area struck will go through a terrible agony before passing away.

Since not all those who committed seppuku were able to endure the pain, usually the daki-kubi would occur as soon as the dagger was plunged into the abdomen. Eventually even the blade became useless on certain occasions, and the samurai might use something symbolic like a fan which, after simulating the cutting of the hara, was immediately performed the decapitation blow by the kaishakunin.

The fan was sometimes used when the samurai was too old to use the blade, or in situations where the risk of retaliation after authorizing a weapon into the hands of the condemned man was high in such circumstances.

In the world of warriors, seppuku was a feat of bravery admired in a samurai who was known to be defeated, fallen in disgrace, or mortally wounded. It meant that he could end his days with his mistakes erased and his reputation not only intact but magnified.

Only through such an attitude could the samurai prove his selflessness, moral uprightness, the reciprocity between his thoughts and deeds, the sincerity of his loyalty, the aura of purity that surrounded his class.

According to the belief of the Japanese of that period, it would be precisely in the region of the belly that a man's authenticity would reside, and by opening the belly, one would know who a man really was.

The cutting open of the abdomen released the samurai's spirit in the most dramatic way, being an extremely painful, slow and unpleasant way to die, causing circulatory shock and/or peritoneal irritation, fainting or ataxia.

Not infrequently, the samurai, after opening the belly, would remain alive for hours or even days, bleeding to death while feeling indescribable pain. This process is called jumonji giri, in which the kaishakunin is not present.

Jigai

While disembowelment was reserved for samurai men, women were granted the right to jigai. Women belonging to aristocratic families, wives of samurai and mainly onna-bugeisha warriors, committed suicide not by disemboweling their bellies, but by cutting their jugular veins with a single blow, using a dagger like a tantō or kaiken.

The motives were similar to those followed by men committing seppuku, and in the jigai, it was to be committed to preserve the woman's dignity or prove her fidelity. This act dates back to the 9th century, and was the way to be followed by the women of Japan's upper military class.

Thus, many resorted to this practice not only when they were unable to fulfill an obligation, but also in cases where a violent act of rape was imminent. Jigai was common in cases of accompanying their lord or husband in death, even when they were condemned to their own execution.

In these cases, jigai could only be done with the master's permission, and thus, the woman could not commit the honorable suicide without prior permission. In another aspect, the female suicide was different from that of the man, and this is found in the liturgical form of the ritual itself.

While the man would open his abdomen to "bare his soul," evidencing his dignity and honor, the woman would insert the blade of a tantō into her throat or heart.

The female ritual was however, less elaborate and did not require a kaishakunin. Before committing suicide, the woman kept her legs together - tying her ankles and knees to each other - to prevent them from inelegantly opening in the fall, exposing her private parts.

Stephen R. Turnbull, a renowned writer and researcher of Japanese history, has provided extensive evidence on the practice of ritual female suicide, especially cases of samurai wives who succeeded each other in pre-modern Japan.

One of the largest mass suicides took place on April 25, 1185 at the Battle of Dan no Ura which led to the destruction of the Taira clan, when Taira no Tomomori is defeated and commits seppuku before being captured by Minamoto's forces; several members of his clan also ended their lives including wives.

Seppuku Cultural factors in suicide

Japanese history is replete with accounts of people who have committed seppuku and other forms of suicide; the art and literature of Japan has long extolled suicide as a noble means of atoning for emotions of guilt and shame.

For an overview of all the intricacies of Japanese behavior and unconscious mental processes discussed in the literature, seppuku deals with an extremely complex issue that is rooted in the history and culture of Japanese society.

Suicide in Japan deals with a complex human behavior that includes various unconscious processes, and for it a multidirectional interpretation from a biopsychosocial perspective is necessary. In this way, suicide should not be analyzed from a psychiatric or other cultural point of view, but from a comprehensive approach to these variables.

Haraquiri was a privilege of the upper classes, while shinjū - a form of suicide committed between intimate people, lovers or family members -, was more common among commoners.

The act of Japanese suicide is generally associated with a meaning of valor or revenge, the saving of the person's or family's name or fame. The analysis of suicide is of utmost importance for the understanding of Japanese culture. In this society, there is an intense and irresistible desire on the part of the Japanese people to establish an identity by belonging to a group.

A strong sense of togetherness (ittaikan) is unconsciously generated among the group and a social sensitivity is manifested about possible disruptions in the harmony of this relationship. However, ostracism of the group is by all means avoided.

The pressures of adaptation to a limited pattern of behavior and thought, and the expectation of total commitment to follow that group, have become unavoidable factors in Japanese thinking.

The consequence of this is that both the pride and shame of an individual are shared by the group and vice versa. Shame, conscious and unconscious, is therefore quite powerful and is often a major factor in suicide in Japan.

Guilt is involved in reciprocal relationships in which a favor "on" is accompanied by the burden of duty of loyalty (giri), which can be very intense and unstable on an emotional level (this contrasts with the notion of guilt present in the West which results from an internal sense that something wrong has been done).

This sense of an unending "duty" seeps into the unconscious of the Japanese, especially in relation to those who have had a careful concern about themselves.

The seppuku, has undeniably marked the history and culture of the country. Risk factors leading to suicide are currently comparable to those present in other countries.

These risk factors include psychiatric disorders, drug abuse, previous suicide attempts, lack of social support systems, advanced age, various types of loss, family repertoire of suicide, accident propensity, and others. Two examples of suicide peculiar to the Japanese context, shinjū and inseki jisatsu, are recurring themes in current Japanese society.