In Japanese history, the term shōgun (将軍 lit. "army commander") about this sound hear, Spanishized as sogún in Spain or shogun in Spanish America, was a historical title in Japan granted directly by the emperor.

As a title, it is the abbreviation of Seii Taishōgun (征夷大将軍 lit. "Great general appeaser of the barbarians"), an appointment that until 1192 had been temporary and was used to refer to the general who commanded the army sent to fight the Emishi, who inhabited the north of the country.

During the twelfth century the shōgun became the de facto ruler of the entire country, although theoretically the emperor was the legitimate ruler and the latter deposited authority in the shōgun to rule on his behalf. During this time, the emperor was forced to completely delegate any civil, military, diplomatic and judicial authority or authority to whoever held that title.

During the first contacts with the West and even in some Asian countries such as China, the shōgun was considered the "king of Japan," ignoring that there were two structures of authority.

Today some writers and historians have compared the shōgun with appellatives such as "military dictator " or "generalissimo " in order to explain his functions to a public unfamiliar with the country's history.

The shōgun government is known in English as shogunate and in Japanese as bakufu (幕府 lit. "government from the maku"). During the history of Japan there were three shogunates and the first one was established in 1192 by Minamoto no Yoritomo, known as the "Kamakura shogunate".

This government was only controlled by three members of the Minamoto clan, as power was usurped by the Hōjō clan, who under the title of regents appointed puppet shoguns as children and young people who were discarded when they turned twenty.

The second shogunate is known as "Ashikaga" and was founded in 1338 by Ashikaga Takauji. During this shogunate fifteen members of the Ashikaga clan held office until a prominent military man of the Azuchi-Momoyama period named Oda Nobunaga overthrew the shōgun in 1573.

The last was the "Tokugawa shogunate," officially instituted by Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1603 and culminating in 1868 after Tokugawa Yoshinobu's resignation from office, when the Meiji emperor resumed his leading role in the country's politics and the figure of the shōgun was abolished.

Shogun Etymology

The term shōgun (将軍 lit. "army commander"), composed of the kanji 将, meaning "commander " and 軍 meaning "army", is the abbreviation of the historical title Seii Taishōgun (征夷大将軍 lit. "Great general appeaser of the barbarians"), which was used to refer to the general who commanded the army sent to fight the tribes of northern Japan.

After the twelfth century, the term was used to designate the leader of the samurai.The administration of a shōgun is called bakufu (幕府) in Japanese and literally means "rule from the maku."

During battles, the head of the samurai army was usually seated on a scissor chair inside a half-open tent called a maku that displayed his respective mon or blazon. The application of the term bakufu to the shōgun's rule shows an extremely strong and representative symbolism.

Shogun Positions

Historically, terms similar to Seii Taishōgun were used with varying degrees of responsibility, although none of them had equal or more importance than the Seii Taishōgun. Some of them were:

- Seitō Taishōgun (征東大将軍 lit. "Commander-in-chief for the pacification of the East.")

- Seisei Taishōgun (征西大将軍 lit. "Commander-in-chief for the pacification of the West")

- Chinjufu Shōgun (鎮守府将軍 lit. "Commander-in-chief of the central pacification headquarters")

- Seiteki Taishōgun (征狄大将軍 lit. "Great general subjugator of the barbarians").

- Mochisetsu Taishōgun (持節大将軍 lit. "Great general of temporary charge").

- Sekke shōgun (摂家将軍 lit. "Great general counselor.")

- Miya shōgun (宮将軍 lit. "Great general of the palace")

Shogun History

Background

At the beginning of the 8th century, the governors of Yamato (the name by which Japan was formerly known) ordered that the existing myths be recorded as a way of legitimizing themselves in the eyes of the populace, and so during this time two important literary works were ordered to be compiled that narrate the origin of Japan from a mythological point of view:

- the Kojiki (古事記)

- and the Nihonshoki (日本書紀).

In the Nihonshoki, completed compiled during 720, it is mentioned in volume 545 that Emperor Sujin established a system called shidō shōgun (四道将軍 lit. "Commanders of the Army of the Four Roads") in which a member of the imperial family was designated for each of four circuits (cardinal points) in which each would serve as shōgun or commander of troops.

The four designated shoguns were as follows:

- Ōbiko no Mikoto was sent to the north (Hokurikudō).

- Takenenunakawawake no Mikoto to the east (Tokaidō)

- Kibitsuhiko no Mikoto to the west (San'yōdō)

- Tanba no Michi no Ushi no Mikoto to the south (Tanba Province)

This narrative is the first record of the use of this word.

During the Nara period (710-794), by orders of the imperial court established in what is now Nara, attention was focused on the Emishi (蝦夷 lit. "barbarians"), inhabitants of northern Japan with whom they had had numerous altercations, in order to subjugate them. In 774 a major revolt broke out, known as the "Thirty-Eight Years' War," where the Emishi used a system of guerrilla warfare against the imperial troops. Several shōgun or generals of troops were appointed to fight the northern tribes without much success and probably the first shōgun in history was Tajihi no Agatamori appointed in 720, followed by Ōtomo Yakamochi in 784, Ki no Kosami in 789 and Ōtomo no Otomaro in 794. It was not until 796 and thanks to Sakanoue no Tamuramaro, that they finally managed to defeat them.

First shōgun

Sakanoue no Tamuramaro

Sakanoue no Tamuramaro (758-811) was a Japanese general who fought against the tribes of northern Japan (settled in the territory that today integrates the provinces of Mutsu and Dewa).

Tamarumaro was the first general to subdue these tribes, integrating his territory to that of the Japanese state. For his military exploits he was named Seii Taishōgun and probably because he was the first to win victory over the northern tribes he is generally recognized as the first shōgun in history.

Fun'ya no Watamaro

Fun'ya no Watamaro (765-823) commanded Japanese troops against two Emishi-dominated areas, in what is now the eastern part of Iwate Prefecture and on the Aomori-Iwate border. He was appointed Seii Taishōgun by Emperor Saga.

Fujiwara no Tadabumi

Fujiwara no Tadabumi (873-947) was appointed shōgun in the year 94017 by the Court to fight against the rebellion led by Taira no Masakado, who had seized the kokuga (provincial government offices) of Hitachi, Kōzuke, Shimozuke, Kazusa, Shimōsa, Awa, Sagami and Izu.

Minamoto no Yoshinaka

Minamoto no Yoshinaka (1154-1184) was a samurai belonging to the Minamoto clan who participated during the Genpei wars against the Taira clan and was confirmed as Seii Taishōgun by the court. Against the Taira he had an important victory during the battle of Kurikara. Yoshinaka died in 1184 fighting the army of his cousins Noriyori and Yoshitsune, who were sent by Minamoto no Yoritomo.

Establishment of the shogunate

By the end of the Heian period (794-1185), there were two rival clans of great importance in the country's political scene: the Minamoto and the Taira. As a result of this enmity, in 1156 a war broke out between the two clans known as the Hōgen rebellion, where the Taira were victorious.

In 1160 another conflict took place between the two factions known as the Heiji rebellion (平治の乱 Heiji no ran), where again the Taira clan was victorious and subsequently its leader, Taira Kiyomori, was given the title of Daijō Daijin ("Great Minister"). The latter constituted the highest rank the emperor of Japan could bestow, so Kiyomori became the de facto ruler of the country.

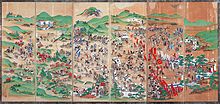

Between 1180 and 118559 conflicts between the two factions resumed leading to a series of civil wars called the Genpei wars. During these clashes Minamoto no Yoshitsune led the clan army on behalf of his elder brother Yoritomo, who remained in Kamakura. Finally, at the battle of Dan no Ura, the Minamoto won the victory.

In 1192 Minamoto no Yoritomo proclaimed himself shōgun, a title that until then had been temporary. This instituted the shogunate as a permanent figurehead, which would last for nearly 700 years until the Meiji Restoration. With the new figure of the shōgun, the emperor would become a mere spectator of the political and economic situation of the country, while the samurai would become the governors.

Kamakura Shogunate

Although Minamoto no Yoritomo took the reins of the country from 1185, his appointment as shōgun became official until 1192, so there are discrepancies in the exact date of the beginning of the Kamakura shogunate (鎌倉幕府 Kamakura bakufu), the first of the three that would exist in Japan.

During this period only three shoguns belonging to the Minamoto clan maintained control of the government as, subsequently, members of the Hōjō clan usurped control of the country under the title of shikken (執権 'regents') between the years 1203 and 1333, the year in which would end

Minamoto no Yoritomo

Yoritomo (1147-1199) was born in Kyoto in 1147, the third son of a total of eight siblings. He was the son of Minamoto no Yoshitomo, who suffered defeat at the hands of the Taira clan in 1160, so the family had to flee.

During the flight, Yoritomo strayed into the mountains and was subsequently captured by the men of Taira no Kiyomori, who decided to spare his life, but instead sent him into exile on the Izu peninsula under the care of Hōjō Tokimasa.

In the company of Tokimasa, he closely followed the political situation in the country and became a skilled archer. In 1178 Yoritomo married a daughter of Tokimasa, and although Tokimasa initially disagreed with the union, he later approved of their relationship.

In 1179, Taira no Kiyomori became dictator by ordering a house arrest against the emperor, so the following year the imperial prince authorized the Minamoto clan to pursue and destroy the Taira clan in order to end the arrest. Yoritomo then began recruiting soldiers for several months, including his father-in-law Tokimasa, who broke off relations with the Taira.

During 1181 and 1182 a severe famine hit the country, so hostilities were halted. Once rice became available, actions resumed in 1183. In the midst of the revolts, Emperor Go-Shirakawa was able to escape and took refuge with the Minamoto, which made his offensive against the Taira legitimate, who abandoned Kyoto in the face of the threat.

Minamoto no Yoshinaka, Yoritomo's cousin, decided to ally himself with the Taira, dissatisfied with having become Yoritomo's vassal. When Yoritomo learned of the betrayal, he sent two half-brothers, Yoshitsune and Noriyori, who attacked him by surprise during the battle of Uji (1184).

With the victory, Yoshitsune could focus his efforts on defeating the Taira, which was summed up by the battle of Dan no Ura on April 25, 1185.

In contrast to the benevolence Kiyomori had shown in sparing his life, Yoritomo ordered that all members of the Taira clan, infantrymen included, be killed. Yoritomo further considered his brother to be a threat and a rival, so his men pursued Yoshitsune until they defeated him during the Battle of Koromogawa in 1189, where the latter committed seppuku by suicide.

After receiving the title of shōgun and having secured control of the government, Yoritomo spent much of his time on hunting expeditions. In 1199 and at the age of 52, he fell from a horse and died, probably from a hemorrhage. His son Yoriie was then left in charge of the government.

Minamoto no Yoriie

Minamoto Yoriie (1182-1204) took control of the country upon the death of his father, Yoritomo, in 1199, but soon became unpopular because of his staunch support for the Hiki clan, who raised him.

In 1202 the emperor granted him the title of shōgun, making the appointment hereditary. The following year Yoriie fell ill, so a power struggle broke out between the Hiki and Hōjō clans. The latter began to ambush the Hiki and killed most of the members, while Yoriie had to relinquish the position in favor of his younger brother, Sanetomo. He was finally assassinated in 1204.

Minamoto no Sanetomo

Minamoto no Sanetomo (1192-1219)63 became shōgun in 1203, after his older brother, Yoriie, was forced to resign. Hōjō Tokimasa became regent that same year and planned to assassinate his own grandson and seize power for his clan. Fortunately for the Minamoto, Hōjō Masako (Yoritomo's widow) learned of such plans and together with her brother, Hōjō Yoshitoki, forced their father to resign his office and live in exile in Izu.

Yoshitoki became regent and the responsibility of government fell to Masako, who was known as "the shōgun nun", as Sanetomo never took up the duty of ruling due to the fact that he used to spend more time writing poetry.

Sanetomo was assassinated in 1219 by his cousin Minamoto Kugyō, who sought to avenge the death of his father Yoriie and proclaimed himself shōgun. Immediately Sanetomo's guards assassinated him leaving the clan with no direct descendants.

Hōjō Regency

After Sanetomo's death, the Minamoto clan had no more heirs because the two brothers had died without offspring. Hōjō Masako then made the decision to raise a boy as young as one year old belonging to a branch of the Fujiwara clan and appointed him shōgun.

In this way the Hōjō clan would perpetuate itself in power for several decades, appointing an infant shōgun and discarding him upon reaching his twenties, achieving puppet rulers to exercise control of the country.

The list of puppet shoguns (first members of the Fujiwara clan and later imperial princes) under the Hōjō regency is as follows:

- Kujō Yoritsune (1218-1256)

- Kujō Yoritsugu (1239-1256)

- Príncipe Munetaka (1242-1274)

- Príncipe Koreyasu (1264-1326)

- Príncipe Hisaaki (1276-1328)

- Príncipe Morikuni(1301-1333)

Kenmu Restoration

In the early fourteenth century the Hōjō clan faced an attempt at imperial restoration, now under Emperor Go-Daigo. When the Hōjō learned of this, they sent an army from Kamakura, but the emperor fled before they arrived, taking the imperial regalia with him. Emperor Go-Daigo sought refuge in Kasagi among warrior monks who welcomed him and prepared for a possible attack.

After attempts by the Hōjō to negotiate with Emperor Go-Daigo to abdicate, and in the face of the latter's refusal, they decided to raise another member of the imperial family to the throne. However, because Go-Daigo had taken away the royal insignia, they were unable to perform the ceremony.

Kusunoki Masashige, an important warrior who would eventually serve as a reference and model for future samurai, fought for Emperor Go-Daigo from a yamashiro (mountain castle). Although his army was not very numerous, the orography of the site provided him with an extraordinary defense.

The castle finally fell in 1332, so Masashige decided to flee and then continue the fight. The emperor was captured and taken to the Hōjō headquarters located in Kyoto and later exiled to the island of Oki. The Hōjō tried to finish off the army led by Masashige, who built another castle in Chihaya with even better defenses than the previous one, so the Hōjō were immobilized.

Masashige's staunch defense prompted Go-Daigo to return to the scene again in 1333. When the Hōjō learned of his return, they decided to send one of their top generals after him-Ashikaga Takauji.

Ashikaga at that time decided that it would be more beneficial for him and his clan to ally with the emperor's side. For this reason, he decided to launch the attack together with his army toward the Hōjō headquarters at Rokuhara.

The blow received by Ashikaga's betrayal had serious consequences for the regents, their army being severely depleted. The final blow would come that same year of 1333, when a warrior named Nitta Yoshisada joined the imperial supporters and increased their forces. Nitta and his army headed for Kamakura and defeated the Hōjō.

During this conflict there were two short-lived shoguns: prince Moriyoshi (1308-1335) was appointed shōgun by his father Emperor Go-Daigo in 1333 and prince Nariyoshi (1326-1344), also known as prince Narinaga, who was appointed shōgun in 1334.

Ashikaga Shogunate

The Ashikaga shogunate (足利幕府 Ashikaga bakufu) was the second military feudal regime and was in effect during the years 1336 until 1573. The period is also known as the Muromachi period and owes its name to the Muromachi area in Kyoto, where the third shōgun Yoshimitsu established his residence.

This shogunate was founded by Ashikaga Takauji and was destroyed in 1573, when Oda Nobunaga deposed the fifteenth and last shōgun Yoshiaki, expelling him from Kyoto.

Ashikaga Takauji

Little is known of the early life of Ashikaga Takauji (1305-1358), as the character came to prominence when the shogunate ordered him to attack Kusunoki Masashige at the Kasagi fortress. Two years after swearing allegiance to the emperor, Takauji destroyed the Hōjō clan's base of operations, opening the way for the emperor to return to the capital and reclaim the throne.

Takauji felt that he had not been properly rewarded, so he went to Kamakura on his own and overthrew the surviving members of the Hōjō clan who had taken over the ruins of Kamakura. In this city, he decided to wait for the reaction of Emperor Go Daigo, who sent an army against him, commanded by Niita Yoshisada.

Yoshisada managed to defeat the vanguard of Takauji's army, who received reinforcements from his allies and marched toward Kyoto, whereupon Go Daigo fled the city. In Kyoto, Yoshisada succeeded in making Takauji and his army flee toward Kyūshū.

Takauji returned in 1336 and defeated Masashige's army, who decided to commit seppuku in the face of defeat. Takauji returned to Kyoto, from where he claimed that Go-Daigo had forfeited his right to the throne and placed his own emperor.

For this reason, two imperial courts would exist for the next fifty years: the Southern Court in Yoshino and the Northern Court in Kyoto. This conflict became known as Nanbokuchō (南北朝 literally, "Southern and Northern Courts"). The emperor of the Northern Court appointed him shōgun in 1338 and his descendants would hold the title for centuries.Takauji eventually died in 1358 from cancer.

Ashikaga Yoshiakira

Ashikaga Yoshiakira (1330-1368) became shōgun upon the death of his father in 1358. Although he initially had trouble entrenching his rule, the major shugo families that could oppose the government (the Shiba, Uesugi, Ōuchi, and Tamana) aligned themselves to the shogunate.

In 1362 troops from the Southern Court commanded by Hosokawa Kiyouji and Kusunoki Masanori marched toward Kyoto with the aim of deposing the shōgun, so he fled. After reorganizing his forces and receiving allied soldiers, the shogunate army recaptured the capital twenty days later. Yoshiakira died in 1368, the same year that Emperor Go-Murakami died.

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358-1408) assumed office upon the death of his father, while still an infant, so Hosokawa Yoriyuki took over the government for some time.

By 1374, the Nanbokuchō Wars had severely weakened the Southern Court throughout the territory except for Kyūshū, so Imagawa Sadayo was sent to control the region. In the face of Sadayo's failure, Yoshimitsu decided to lead the campaign, returning triumphant.

Yoshimitsu then entered into diplomatic relations with the Ming dynasty of China, which had just taken control of the country after the invasion of the Mongols, who had ruled as the Yuan dynasty. In order to normalize relations between the two countries, Yoshimitsu fought the wakō, Japanese pirates who plagued the coasts of Korea and China.

Yoshimitsu ended the wars between the two imperial courts in 1392, when he persuaded Emperor Go-Kameyama of the Southern Court to surrender and the status of emperor was obtained by Emperor Go-Komatsu, ending the imperial dispute.

Yoshimitsu was also a great promoter of the arts, which is reflected in the Kinkaku-ji (金閣寺 "Temple of the Golden Pavilion"), which he ordered to be built during his rule, with the aim of serving as a retreat house.

He died suddenly in 1408 from illness at the age of fifty.

Ashikaga Yoshimochi

Ashikaga Yoshimochi (1386-1428) was the third son of Yoshimitsu and was appointed shōgun in 1394, after his father retired from the post. He retired in 1423, ceding the title to his son Yoshikazu. He died in 1428.

Ashikaga Yoshikazu

Ashikaga Yoshikazu (1407-1425) ruled for only two years, after his father ceded the title to him in 1423, as he died in 1425 due to a life marked by high alcohol abuse.

Ashikaga Yoshinori

Ashikaga Yoshinori (1394-1441) took the leadership of the country's politics and fought against the growing influence of the shugo in a despotic manner.

Because of his severity, he is referred to in some chronicles as "the evil shōgun. " He was assassinated by a shugo-daimyō in 1441, which marked a decline in the power of the shōgun figure and increased violence in the succession struggle between the various shugo. This would result in the Ōnin war.

Ashikaga Yoshikatsu

Ashikaga Yoshikatsu (1434-1443) was appointed shōgun upon the death of Yoshinori, as a mere eight-year-old boy. He died shortly after taking power in 1443.

Ashikaga Yoshimasa

Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1436-1490) was appointed shōgun until 1449, so for six years he did not hold that post. During his tenure the country experienced one of its greatest wars: the Ōnin War. In 1464, Yoshimasa had no descendants, so he promised the succession to his brother, a Buddhist monk, who, in response to this offer, left the monastic life and took the name Yoshimi.

A year later, Yoshimasa's son Yoshihisa was born, which sparked the struggle for the succession of the government. The country was plunged into a ten-year war, which would mark the beginning of a period called the Sengoku period or "Warring States period. " During the conflict, Yoshimasa decided to abdicate in favor of his son by retiring in 1474.

Yoshimasa is considered a patron of the arts, as he supported the development of the tea ceremony and began the construction of Ginkaku-ji (銀閣寺 "Temple of the Silver Pavilion"), which was intended to be a replica of the splendorous Temple of the Golden Pavilion built by his grandfather.

Ashikaga Yoshihisa

Ashikaga Yoshihisa (1465-1489), from the time he took the position of shōgun and even as an infant, had a strong conviction to restore the military power that his predecessors had enjoyed, as soon as he was old enough.

Such an opportunity came in 1487, when his 46 vassals in Ōmi Province requested him to take action against Rokkaku Takayori, a shugo of the province who was expropriating land.

Yoshihisa personally took charge of the expedition and his army besieged Takayori's troops at Kannonji Castle, while he remained in a nearby camp at Magari village. Here Yoshihisa fell ill and died, so his army lifted the siege and returned to Kyoto. Because there was no direct heir, his cousin Yoshitane succeeded him the following year.

Ashikaga Yoshitane

Ashikaga Yoshitane (1466-1523) took the post of shōgun a year after his cousin's death, but in 1491 he was defeated in battle at Shōgakuji to Hosokawa Masamoto's troops, so he had to flee. His enemies appointed Ashikaga Yoshizumi as shōgun, although he eventually regained his place.

Ashikaga Yoshizumi

Ashikaga Yoshizumi (1480-1511) was appointed shōgun at a very young age and during his tenure was only a puppet ruler under Hosokawa Masamoto. In 1508, a leading shugo of the Ōuchi clan conspired together with one of Masamoto's sons to bring Yoshitane back to power, whereupon Yoshizumi was removed.

Ashikaga Yoshiharu

Ashikaga Yoshiharu (1511-1550) came to power in 1521, after Yoshitane fled the capital at the time one of Masamoto's sons, Takakuni, was appointed kanrei.98 Yoshiharu was a puppet of Takakuni, although he eventually escaped from the capital seeking to flee the Hosokawa's rule. He died in Ōmi province.

Ashikaga Yoshiteru

Ashikaga Yoshiteru (1536-1565) took over the leadership of the shogunate in 1546.98 In 1549 the Hosokawa clan succumbed to their vassals, the Miyoshi, who continued their dominance over the shogunate of the country.

Yoshiteru sought to declare shōgun autonomy in 1565, but the Miyoshi clan's response was to send an agent named Matsunaga Hisahide to assassinate him.

Ashikaga Yoshihide

Ashikaga Yoshihide (1538-1568) was appointed shōgun in 1568,99 supported by those who had assassinated his predecessor years earlier.100 Another possible candidate for the government was Ashikaga Yoshiaki, who was then a Buddhist monk who managed to escape in order to find who would support him in his cause.

Oda Nobunaga then decided to support Yoshiaki and took control of Kyoto to secure "the emperor's interests. " Once Nobunaga had the situation under control in the capital, Emperor Ōgimachi appointed Yoshiaki shōgun.

Yoshihide was forced to flee to the island of Shikoku, where he died in September of the same year, after having been shōgun for only a few months.

Ashikaga Yoshiaki

Once Ashikaga Yoshiaki (1537-1597) took office on the emperor's orders, the emperor ordered both Yoshiaki and Oda Nobunaga to help him recover property that had belonged to the imperial family. Yoshiaki also wanted to appoint Nobunaga as kanrei, but Nobunaga refused to subordinate himself to the shogunate and tried to overpower the shōgun by force.

In 1573 Yoshiaki called on nearby daimyō and religious authorities to take up arms against Nobunaga, while he fortified himself south of Kyoto awaiting reinforcements.

Nobunaga easily defeated Yoshiaki and spared his life, condemning him to exile. Officially Yoshiaki's rule ended until 1588 when he resigned from office, although most historians claim that the shogunate ended in that same year, as it did de facto.

End of the Ashikaga shogunate: The three "great unifiers of Japan".

Only a week after securing the retirement of the shōgun Yoshiaki, Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) managed to convince the emperor to make the era name change to "Tenshō" as a symbol of the establishment of a new political system. The emperor also granted him the title of Udaijin (右大臣 lit. "minister of the right"), which he held for four years, until, citing military duties, he delegated it to his son.

Oda Nobunaga

Nobunaga had been born in 1534 in Owari province and until 1560 had been a minor daimyō. In 1560 Nobunaga achieved fame and recognition by defeating Imagawa Yoshimoto's large army during the Battle of Okehazama. After helping Yoshiaki to the shogunate, he embarked on a campaign to gain control of the central part of the country.

In 1570 he defeated the Azai and Asakura clans during the battle of Anegawa and in 1575 he defeated the legendary cavalry of the Takeda clan during the battle of Nagashino. Other of his main enemies were the Ikkō-Ikki warrior monks, members of the Buddhist sect of the Jōdo Shinshū.

With the Ikkō-Ikki Nobunaga maintained a twelve-year rivalry, ten of which he devoted to the longest siege in Japanese history: the siege of the fortress Ishiyama Hongan-ji.

In 1576 he built Azuchi Castle, which became his base of operations. By 1582 Nobunaga dominated almost all of central Japan, as well as its two main roads: the Tōkaidō and the Nakasendō, so he decided to extend his rule westward.

Two of his main generals were entrusted with this task: Toyotomi Hideyoshi would pacify the southern part of the west coast of the Seto Inland Sea, in Honshū, while Mitsuhide Akechi would go along the northern coast of the Sea of Japan. During the summer of the same year, Hideyoshi was detained during the siege of Takamatsu Castle, which was controlled by the Mōri clan.

Hideyoshi asked Nobunaga for reinforcements, who ordered Mitsuhide to go ahead and then join them. Mitsuhide, in the middle of the march, decided to turn back to Kyoto, where Nobunaga had decided to stay at the Honnō temple accompanied only by his personal guard. Mitsuhide attacked the temple and set it on fire in what is known as the "Honnōji Incident," where Nobunaga died committing seppuku.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598) came from a family of very humble origins and his father had been a peasant who had fought in Nobunaga's army as an ashigaru soldier until being shot by an arquebus forced him to retire.

Hideyoshi followed in his father's footsteps and thanks to his prowess on the battlefield he was quickly promoted on several occasions, eventually becoming one of the leading generals of the Oda clan.

During the "Honnōji Incident," Hideyoshi was besieging Takamatsu Castle and quickly received news of his master's death, so he immediately made a truce with the Mōri clan and returned to Kyoto by forced march.

The armies of the newly self-appointed shōgun Akechi Mitsuhide and Hideyoshi met on the banks of the Yodo River, very close to a small village called Yamazaki, from which the confrontation gets its name. Hideyoshi was victorious and Mitsuhide was forced to escape. During his escape a group of peasants killed him, thus ending his rule of only 13 days.

Avenging the death of his former master gave him the expected opportunity to become the highest military authority in the country and for the next two years he confronted and defeated the rivals who opposed him. In 1585, having secured control of the center of the country, he began to advance westward, beyond the reach Nobunaga had achieved.

By 1591 Hideyoshi had succeeded in unifying the country, so he decided to conquer China.Hideyoshi requested the assistance of the Joseon dynasty in Korea to attack the Ming dynasty and be guaranteed safe passage, which the Korean government refused.

Korea was then the scene of a two massive invasions by Japanese troops between 1592 and 1598, which ended with the death of Hideyoshi, who remained in Japan throughout.

Because Hideyoshi had no royal ancestry and did not come from any of the historical Japanese clans, he was never granted the title of shōgun. Instead, he received a lesser title: that of Kanpaku (関白 regent) in 1595, that of Daijō Daijin (太政大臣) in 1586, and finally decided to use the title of Taikō (太閤 "retired Kanpaku").

Tokugawa Ieyasu

Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616) spent most of his childhood as a hostage of the court of Imagawa Yoshimoto, as his clan was a vassal of the Imagawa. After Oda Nobunaga's victory over Yoshimoto, many of the daimyō defected, either becoming independent or declaring themselves allies of the Oda clan, the most notable of the latter being the case of Ieyasu himself.

Under Nobunaga's orders, Ieyasu fought in 1564 against the Ikkō-ikki of Mikawa province and in 1570 fought during the Battle of Anegawa alongside Nobunaga's forces. In 1572 he faced one of his greatest military challenges of his life: the Battle of Mikatagahara, where his army was defeated by the cavalry of Takeda Shingen, who would die the following year from an arquebus shot.

In 1575 he was present at the battle of Nagashino where the Takeda clan was defeated and from that time on he was dedicated to consolidating his military position, even after Toyotomi Hideyoshi took control of the country.

Because Ieyasu's fief was in the center of the country, he avoided attending pacification campaigns in Shikoku and Kyūshū, although he had to confront the late Hōjō clan in 1590, during the siege of Odawara. Thanks to the victory against the Hōjō, Hideyoshi gave him the confiscated lands, so he moved his capital to Edo (now Tokyo).

His new location in Kyūshū also allowed him to avoid the responsibility of fighting during the Japanese invasions of Korea, a war that greatly weakened the armies of his main rivals.

Battle of Sekigahara

After Hideyoshi's death, Tokugawa Ieyasu began to establish a series of alliances with powerful figures in the country through arranged marriages, whereupon Ishida Mitsunari, one of the five bugyō (奉行 magistrate), began to unify all those against the figure of Ieyasu.

On August 22, 1599, while Ieyasu was organizing his army with the intention of confronting a rebellious daimyō named Uesugi Kagekatsu, Mitsunari decided to act backed by the other bugyō and three of the four tairō (大老 lit. "Great Elder"), who sent a formal complaint against Ieyasu accusing him of 13 separate charges.

Among the charges were that he had given daughters and sons in marriage for political purposes and had taken possession of Osaka Castle, Hideyoshi's former residence, as his own. Ieyasu interpreted the missive as a clear declaration of war, so virtually every daimyō in the country enlisted, either in Mitsunari's "Army of the West" or Ieyasu's "Army of the East. "

The two armies clashed in what is known as the Battle of Sekigahara (関ヶ原の戦い Sekigahara no tatakai), which took place on October 21 (September 15 in the old Chinese calendar) in the year 1600 at Sekigahara (now Gifu Prefecture). In that battle, Ieyasu emerged victorious after several "Western Army" generals decided to switch sides in the midst of the conflict.

Ishida Mitsunari was forced to flee, although he was later captured and beheaded in Kyoto. With this victory, Ieyasu would become the country's top political and military figure.

Tokugawa Shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (1603-1868), also known as the Edo shogunate, Tokugawa bakufu or, by its original Japanese name, Edo bakufu (江戸幕府), was the third and last shogunate to hold power in Japan. This shogunate was established by Tokugawa Ieyasu and a total of fifteen shoguns held power for over 250 years.

This period ended under multiple pressures with the handover of power from Tokugawa Yoshinobu to Emperor Meiji in 1868. Thereafter, the shogunate was abolished and the emperor gained military and political power in the country, triggering the Meiji Restoration, which would radically transform the country for the rest of the 19th century.

Tokugawa Ieyasu

To reward all those who had supported him in victory, Ieyasu confiscated the lands of 90 families, which in total amounted to 6.5 million koku.

In 1603, Ieyasu was officially appointed by Emperor Go-Yōzei as shōgun, a position he would hold for only two years, for in 1605 he decided to abdicate in favor of his son Hidetada, taking for himself the title of Ōgosho (大御所 "cloistered shōgun").

During his rule, two types of feudal lords were established: the fudai-daimyō (譜代大名) and the tozama-daimyō (外様大名). The fudai, 176 in all, were those who had been loyal before or during the battle of Sekigahara, while the tozama, 86 in all, were those whose loyalty had been secured only after the battle, so they were relegated from the government's main circle of influence.

On the other hand, he made the city of Edo the seat of his government and began rebuilding Edo Castle, ordering the daimyō to assist in the reconstruction and expansion of the city.

Tokugawa Hidetada

Tokugawa Hidetada (1579-1632) was the third son of Ieyasu and became shōgun in 1605 when his father abdicated, becoming the second Tokugawa shōgun.

He was present during the campaign leading up to the Battle of Sekigahara, but was unable to participate in it because he was delayed during the siege of Ueda Castle. Hidetada abdicated the shogunate in 1623 in favor of his son Hidemitsu, although he retained authority of the country until his death in 1632.

Tokugawa Iemitsu

Tokugawa Iemitsu (1604-1651) was appointed shōgun in 1623 at only nineteen years of age, although his father retained power until his death in 1632.

Within months of his father's death, Iemitsu resolved to improve the administration of the shogunate and among his main measures formalized the junkenshi, a group of inspectors who frequently visited the daimyō's domains to ensure that everything was in order.

During his rule there was the first great famine of the Tokugawa shogunate, which lasted from 1630 to 1640-1641, leading to peasant protests in 1632, 1633, and 1635.

The Shimabara rebellion of 1637-1638 was the most dramatic consequence of the deteriorating relationship with the government due to this crisis, in which Catholic peasants clashed against the government's large army.

Although this protest had no religious or political purpose, this event apparently convinced Iemitsu to restrict Christianity in Japan for good, so he issued an order in 1639 banning the religion and preventing Portuguese priests from entering the country on pain of death, as well as excluding Japan from the world.

Iemitsu died in 1651, being the first to die during his mandate and not having left it by abdication.

As ōgosho he maintained control of the government. He also had to face the threat of Toyotomi Hideyori, son of Hideyoshi, as some supporters claimed he was the legitimate successor to the government and many samurai and rōnin allied with him in order to fight the shogunate, which resulted in two battles summarized under the name "siege of Osaka".

In 1614, the Tokugawa, under the leadership of Ōgosho Ieyasu and shōgun Hidetada, led a large army to Osaka Castle in what became known as the "Winter Siege of Osaka. " Eventually, Ieyasu made a deal with Hideyori's mother, Yodogimi, and the Tokugawa troops began to fill the moat with sand, whereupon Ieyasu returned to Sunpu.

After Hideyori again refused to leave the castle, the latter was besieged, in what became known as the "Summer Siege of Osaka. " Finally, in late 1615, the castle fell during the Battle of Tennōji, where the defenders were killed, including Hideyori, who decided to commit seppuku. With the Toyotomi exterminated, there were no longer serious threats to Tokugawa domination of Japan.

Ieyasu passed away peacefully in 1616.

Tokugawa Ietsuna

Tokugawa Ietsuna (1641-1680) was appointed shōgun at the age of ten, whereupon a group of advisors and officials took charge of the shogunate government. Minor events occurred during his tenure, the most significant being the Great Meireki Fire of 1657 in Edo.

Ietsuna died in 1680 without leaving any descendants, so the chief councilors decided that Tsunayoshi, Ietsuna's younger brother, would be the chosen one.

Tokugawa Tsunayoshi

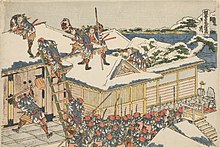

During Tsunayoshi's tenure the event known as the "47 rōnin" occurred.

Tokugawa Tsunayoshi (1646-1709) was the fifth Tokugawa shōgun. At the age of six he became daimyō of a fief of 150,000 koku and ten years later was transferred to a larger one valued at 250,000 koku.

Upon the death of the shōgun he was chosen as successor and from the beginning showed signs of desiring autocratic rule by forcing the resignation of Sakai Tadakiyo, who had served as one of the shogunate's chief advisors. During his tenure daimyos were dispossessed of their lands with a total of land valued at 1.6 million koku.

In the late 17th century he extended a series of draconian laws to protect animals, particularly dogs (because he was born in the year of the dog according to the Chinese calendar) and an apprentice was even executed for injuring one.Unable to cope with so many canines, shelters were built in the suburbs where it is believed that 50,000 of these animals were fed with rice and dried fish.

During that time many hunters were imprisoned for hunting, fishermen for killing fish, as well as hundreds of peasants who had killed the animals that ate their crops. Such measures earned him the nickname "the dog shōgun". He was one of the first examples of laws against animal abuse.

Tokugawa Ienobu

Tokugawa Ienobu (1662-1712) took over the government upon the death of his uncle Tsunayoshi in 1709. In response to popular expectations of a different government, one of his first actions was to abolish strict animal protection laws, as well as the release of 8831 prisoners through a general amnesty.

His main advisor was the politician and scholar Arai Hakuseki, who had also served as his tutor. Hakuseki had a humanistic view of resolving the conflicts and needs of the people, which was reflected in the attitude of the shogunate during a peasant revolt in 1711.

During that revolt, in response to the demands of some officials to "act with an iron fist," Hakuseki asserted that "officials should listen as parents to the grievances of the people. "

Ienobu died in 1712.

Tokugawa Ietsugu

Tokugawa Ietsugu (1709-1716) became the seventh shōgun while only an infant, so Arai Hakuseki continued to have considerable influence in the government. Due to his untimely death he left no heirs, so he was the last of the main line of the Tokugawa clan, although there were more collateral branches.

Tokugawa Yoshimune

Tokugawa Yoshimune (1684-1751) was the daimyō of Kii province upon the death of Ietsugu and, lacking a direct descendant, was chosen to be the successor to the shogunate. Yoshimune formed his own intelligence agency called oniwaban, whose members were tasked with informing him of the activities of daimyō and officials.

During his rule he implemented the Kyōhō reforms, which sought to make the shogunate a solvent institution.

Yoshimune decided to abdicate in 1745 in favor of his eldest son Ieshige, taking for himself the title of Ōgosho. He died in 1751.

During his tenure the event commonly known as the "47 rōnin" took place, a story that has served as an example of the samurai code of conduct called bushidō.

Tsunayoshi died in 1709 without direct descendants, so his nephew and adopted son, Ienobu, succeeded him.

Tokugawa Ieshige

Tokugawa Ieshige (1711-1761) was appointed shōgun by his father in 1745. Ieshige is regarded as one of the least capable shōgun, although thanks to his father's reforms the shogunate reached 3 million gold coins in reserves in the year 1770, the highest figure in the entire Tokugawa shogunate.

During his rule there were a large number of peasant revolts, and robberies increased considerably. There were also a large number of natural disasters such as storms, volcanic eruptions, famines, epidemics and fires, which helped to increase resentment against the government.

Ieshige decided to abdicate in 1760, passing away only a year later.

Tokugawa Ieharu

Tokugawa Ieharu (1737-1786) was appointed shōgun at the time his father decided to retire. His government faced a severe famine known as the Tenmei famine that began in 1782 and continued until 1787 and left an unknown death toll.

In 1786 the shōgun fell severely ill and passed away.

Tokugawa Ienari

Tokugawa Ienari (1773-1841) was the longest-serving shōgun of the entire Tokugawa clan, with a total of fifty years in power. Ienari had a large number of concubines (estimated at forty) and a large number of children (fifty-five in total).

During the early part of his rule he promoted the Kansei reforms devised by his chief advisor Matsudaira Sadanobu, although upon the latter's death he decided to retreat into a life of excess.

He retired from government in 1837 and, in early 1841, began to suffer severe abdominal pains, passing away just three weeks later.

Tokugawa Ieyoshi

Tokugawa Ieyoshi (1793-1853) ascended to power after his father's retirement and blindly supported the advisor Mizuno Tadakuni in implementing a program of radical shogunate reform known as the "Tenpō reforms". This reform had disastrous results for the government and further weakened it. Ieyoshi died shortly after the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry in 1853.

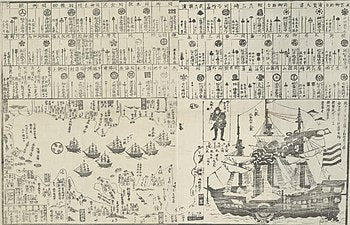

Perry forced Japan to break isolation in what became known as the Black Ships (黒船 kurofune) and forced them to allow trade with the rest of the world.

Tokugawa Iesada

Tokugawa Iesada (1824-1858) was appointed shōgun within days of Perry's retirement. Iesada signed the so-called "Unequal Treaties" (Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Friendship, Harris Treaty, Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Friendship and Commerce) during the Kanagawa Convention, thus beginning the stage known as bakumatsu.

He died suddenly in 1858, leading to speculation that he was actually assassinated for giving in to international demands.

Tokugawa Iemochi

Tokugawa Iemochi (1846-1866) was elected shōgun after the unexpected death of his predecessor, as the latter had had no offspring. Because of Iemochi's young age, governmental affairs were attended to by his chief advisors.

He passed away at the early age of twenty.

Tokugawa Yoshinobu

Tokugawa Yoshinobu (1837-1913), also known as Keiki, assumed power in 1867 and attempted to establish a series of reforms to modernize the armed forces. The shogunate was a rather weak institution at this time and the various daimyō had become more independent, so they feared a resurgence of the shogunate in Yoshinobu's hands.

As a result, daimyos and samurai from the domains of Satsuma, Chōshū and Tosa formed an alliance to fight the shogunate army under the motto Sonnō jōi (尊王攘夷 "Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians"). Yoshinobu, accepting that he could not win such a civil war, decided to resign in 1867 and was arrested and stripped of his land. He was later allowed to live in retirement.

On January 3, 1868, the Imperial Court in Kyoto declared the restoration of the emperor's power in what was called the "Meiji Restoration," bringing an end to the Tokugawa regime and shogun rule in the country.

In 1902, Emperor Meiji allowed him to reestablish his own house as a Tokugawa branch (bekke) with the highest of noble titles, that of prince (kōshaku), for his loyal service to Japan.

Prince Tokugawa Yoshinobu died in 1913.

End of the shogunate

In early 1868, after Yoshinobu's resignation, supporters of the shogunate clashed against the faction loyal to the emperor during the conflict known as the Boshin War (戊辰戦争 Boshin Sensō, "War of the Year of the Dragon"), which would culminate until the following year.

After the victory, the new government carried out the unification of the country under the single, legitimate power of the imperial court. The emperor's residence was moved from Kyoto to Edo at the end of 1868, and the political and military power of the fiefdoms was progressively abolished, soon being transformed into prefectures whose governors were appointed by the emperor.

The samurai class was abolished, which allowed many samurai to engage in administrative or commercial work, but drove many others into poverty.

Shogun Administration

From the establishment of the shogunate, the shōgun became the administrative and political leader of the country, while the emperor's powers were only subservient to the religious sphere.

Theoretically, the emperor constituted the highest political authority, while the shōgun constituted only the emperor's deputy, who had conferred on the shōgun the privilege of ruling on his behalf.

The administration of the country lasted for seven centuries at the hands of the shoguns, who established various dependencies to maintain control of the territory.

During the Kamakura shogunate

After Yoritomo took control of the entire country, the shogunate extended a mixed system of military control and civil administration.

As in European feudalism, the system as a whole was based on the personal and military relationships of the shōgun and regional subordinates called gokenin, who collected taxes and administered their lands, although the main difference from the European model was that they did not have possession of their land or the peasants who worked it.

The shogunate controlled the lives and properties of their direct subordinates and delegated the responsibility for the administration of distant lands to various officials. The emperor and the Kyoto Court were allowed to maintain control over their lands, as well as autonomy in the collection of taxes, while having the freedom to freely appoint their administrators.

The various offices held during this period were:

- Shikken (執権 Regent) - This office belonged to the Hōjō clan from 1203 until the end of the Kamakura shogunate and allowed them to rule in the shadow of the shōgun, because the clan did not have the necessary social rank to officially hold such an office.

- Rensho (連署 lit. "Co-signatory") - This office was established in 1225 as a way of sharing governance with the various branches of the Hōjō clan. On official documents it was a requirement that the signatures of both the regent and the co-signatory appear.

- Hyōjōshū (評定衆 State Council) - Founded in 1225 as a way of sharing the responsibility of governing. Decisions were made by simple majority votes.

- Kumonjo (公問所 Public Document Office).- Established by Minamoto no Yoritomo in 1184 as the major administrative office of his government. Subsequent to the establishment of the shogunate it was renamed Mandokoro.

- Mandokoro (政所 Administrative Council) - It was established in 1191 by Yoritomo in order to replace the Kumonjo. After the Hōjō took control of the country, the office was devoted exclusively to running the government's finances.

- Monchūjo (問注所 Board of Inquiry) - Founded in 1184 by Yoritomo to handle legal matters such as lawsuits and appeals.

- Samurai dokoro (侍所).- Founded by Yoritomo in 1180 with the object of regulating the activities of the gokenin.

- Hikitsukeshū (引付衆).- Established as a judicial court by Hōjō Tokiyori in 1249. Among other matters it dealt with issues related to legal matters of land ownership and taxation.

- Kyōto shugo (京都守護).- The position of military governor of Kyoto was established at the beginning of the shogunate and its purpose was to see matters related to the imperial court on behalf of the shogunate. It was replaced by the Rokuhara tandai in 1221.

- Rokuhara tandai (六波羅探題).- It was established in 1221 with the aim of replacing the Kyōto shugo and its scope extended not only to Kyoto, but to the entire southwestern part of the country.

- Chinzei bugyō (鎮西奉行).- This office was established for the purpose of appointing two commissioners to watch over the affairs of Kyūshū, especially the activities of the Minamoto vassals.

- Chinzei tandai (鎮西探題) - Attended to the political, legal and military affairs of Kyushu. It was established in 1293 as a result of the threat of invasion by the Mongols.

- Ōshū sōbugyō (奥州総奉行).- This office was created for the purpose of looking after the interests of the shogunate in the north of the country (Honshū).

- Shugo (守護 lit. "military governor") - A post founded by Minamoto no Yoritomo in order to maintain control over the provinces of the country. Over time the position became hereditary and within its functions were to administer the province, keep the peace and investigate crimes occurring in its territory.

- Jitō (地頭) - These were officials of the highest confidence within the shogunate who served as overseers of the state. They were in charge of collecting taxes and ensuring their proper distribution. Eventually it became a hereditary position.

During the Ashikaga shogunate

The Ashikaga shogunate inherited much of the features of the previous shogunate's administration, and key offices were retained.

Because the territory occupied by the Hōjō and that of the emperor's allies were confiscated, the territory directly ruled by the Ashikaga reached 25% of the total country, giving rise to the birth of a new class of "warlords" called daimyō, who resisted submission to the rule of the shogunate. Possession of land was furthermore denied to the samurai.

The administrative offices in the Ashikaga shogunate were as follows:

- Kanrei (管領).- Their function consisted of the shōgun in the administration of the government. One of his main responsibilities was to oversee the relationship between the shogunate and the military governors (shugo).

- Hyōjōshū (評定衆).- See under Administration during the Kamakura shogunate.

- Hikitsuke (引付) - See under Administration during the Kamakura shogunate.

- Mandokoro (政所) - See under Administration during the Kamakura shogunate.

- Samurai dokoro (侍所) - See under Administration during the Kamakura shogunate.

- Monchūjo (問注所).- During this shogunate many of the powers of this body were deposited in the Mandokoro, so that only records were kept in this office.

- Kamakura kubō (鎌倉公方).- During the shogunate the term kubō referred to both the shōgun and its military governors. The post was established in 1336 for the purpose of monitoring the shogunate's interests in Kamakura and eastern Kamakura.

- Kantō kanrei (関東 管領).- For the purpose of overseeing the Kantō region, this Kyoto-based office was established in 1349. It was occupied by members of the various branches of the Uesugi clan from the late 14th century.

- Kyūshū tandai (九州 探題).- See under Administration during the Kamakura shogunate.

- Ōshū tandai (奥州 探題).- See under Administration during the Kamakura shogunate.

- Ushū tandai (羽州 探題).- Office created to guard northwestern Honshū (Ushū).

- Shugo (守護) - See in Administration during the Kamakura shogunate.

- Shugodai (守護代).- Because it was rare during this period for shugo to live in the domains where they were assigned to rule, shugodai were the ones who bore the responsibility of governance.

- Jitō (地頭).

- Jitōdai (地頭代).- Within the jitō system, some vassals had to guard multiple fiefs, so the jitōdai took over the rule of those additional regions.

During the Tokugawa shogunate

During the Tokugawa shogunate the duties of the shōgun were summed up as "preserving the emperor and his palace out of danger, and preserving peace and tranquility in the Empire in all its directions. "Ikeda Mitsumasa, daimyō of Bizen, defined the administration of the shogunate in 1632 as follows:

The administration system of this era is considered "centralized feudalism, " as the country was divided into about 200 fiefdoms governed by daimyō divided into three categories: the fudai, the shinpan and the tozama, all of which were under the control of the shōgun.

During this era the administration of the government depended on the following offices:

- Tairō (大老 lit. "Grand elder").-The function of the tairō was to provide Japan with a capable temporary leader in case the shōgun was absent or incapacitated, although he was rarely filled.

- Rōjū (老中 lit. "veteran counselor") - These were veteran government officials who saw to the smooth running of the government as a whole, as well as the internal and external affairs of the country. They were usually chosen four or five from among the fudai-daimyō.

- Edo machi bugyō (江戸町奉行 lit. "Edo city magistrate") - These were officials of the shogunate charged with seeing to the affairs of the city concerning its inhabitants and merchants. Candidates were chosen from among the hatamoto.

- Kanjō bugyō (勘定奉行 Commissioners of finance) - Handled accounting and financial affairs and reported directly to the rōjū. The occupants of this post (usually four) were chosen from among the hatamoto.

- Daikan (代官).- Although this position existed before the Tokugawa shogunate, it became official only until this period. These local governors supervised and managed the territories of the shogunate.

- Kanjō ginmiyaku (勧請吟味役).- This office, created in 1682, was responsible for investigating and supervising the operations of the Kanjō bugyō, although theoretically they were of lower rank. They reported directly to the rōjū.

- Ōmetsuke (大目付).- Office created in 1632 for the purpose of looking into road safety, the activities of daimyō or troublesome groups, such as Catholic missionaries and their followers. They reported to the rōjū.

- Ongoku bugyō (遠國奉行?).- The position was similar to that of Edo machi bugyō, except that they served in different locations such as Kyoto and Osaka.

- Ōbangashira (大番頭 Captain of the Grand Guard).- They were responsible for the security of the three castles related to the shogunate: the Edo castle, Osaka castle and Kyoto castle.

- Rusui (留守居) - Supervised and, if necessary, defended Edo Castle.

- Kinrizuki (禁裏附).- Served as inspectors of the imperial palace.

- Kōke (高家).- They were government officials in charge of carrying out the official ceremonies and rituals of the shogunate. The position was hereditary and they also served as representatives of the shogunate at temples and shrines.

- Sobashū (側衆).- Office established in 1653 under the direct orders of the shōgun.

- Sōshaban (奏者番).- They were officials in charge of keeping the agenda and organizing the shōgun's ceremonies.

- Jisha bugyō (寺社奉行).- Commissioned at temples and shrines. There were usually four members who oversaw religious affairs.

- Kyōto Shoshidai (京都所司代)- This office was originally founded by Oda Nobunaga and Hideyoshi Toyotomi for the purpose of monitoring activities in Kyoto, especially regarding the imperial court and surrounding territories.

- Ōsaka jōdai (大坂城代) - Position whose duty was to maintain the troops of Osaka Castle. The position was reserved for daimyos of relative importance who were generally promoted to Kyoto Shoshidai or rōjū.

- Sobayōnin (側用人 lit. "Great chamberlain") - He was in charge of relaying messages between the shōgun and the rōjū.

- Wakadoshiyori (若年寄 lit. "Young elders") - Assisted the rōjū and supervised the hatamoto and gokenin. In the event of war, they led the hatamoto into battle.

- Koshō tōdori (小姓頭取) / Konando tōdori (小納戸頭取?).- Served as the heads of the shogunal pages and attendants.

- Metsuke (目付 Inspector).- Performed policing and law enforcement at many levels.

- Shoinban gashira (書院番頭? Escort captains) / Koshōgumiban gashira (小姓組頭 Captains of the inner guard) / Shinban gashira (新番頭 Captains of the new guard) - Various escorts that operated under the command of the wakadoshiyori during the war.

Shogun Relationship to the Emperor

From the time Minamoto no Yoritomo made the figure of the shōgun a permanent, hereditary position and until the Meiji Restoration there were two ruling classes in Japan:

that of the emperor or tennō (天皇 lit. "Heavenly Sovereign"), who acted as "chief priest" of the country's official religion, Shinto, and that of the shōgun, head of the army who also enjoyed civil, military, diplomatic, and judicial authority. Although in theory the shōgun was a servant of the emperor, the shōgun became the real power behind the throne.

It is noteworthy that no shōgun attempted to usurp the throne, even though they had the military power of the territory at their disposal. There were two main reasons for this:

- Theoretically the shōgun received power from the emperor, so this was his symbol of authority.

- There was a sentimentalist tradition created by priests and religious people who traced the imperial line from the "age of the gods" in an "eternal line unbroken through the ages." According to Japanese mythology, the emperor was a direct descendant of Amaterasu, goddess of the Sun.

Unable to usurp the throne, the shoguns sought throughout history to keep the emperor away from the country's political activity, relegating them from the sphere of influence. One of the few powers that the imperial house was able to retain was that of being able to "control the weather" through the designation of the nengō or Japanese eras and the issuance of calendars.

It is worth noting two historical attempts by the emperor to regain the power they enjoyed before the establishment of the shogunate. In 1219 Emperor Go-Toba accused the Hōjō of being outlaws.

Imperial troops were mobilized, giving rise to the Jōkyū War (1219 - 1221), which would culminate in the Third Battle of Uji. During this, the imperial troops were defeated and Emperor Go-Toba exiled. With Go-Toba's defeat, samurai rule over the country was confirmed.

In the early 14th century Emperor Go-Daigo decided to rebel but the Hōjō, who were then serving as regents, sent an army from Kamakura. The emperor fled before the troops arrived and took the imperial regalia with him. The shōgun appointed his own emperor, giving rise to the Nanbokuchō era (南北朝 lit. "Southern and Northern Courts").

During the 1850s and 1860s the shogunate came under severe pressure both externally from foreign powers and internally. It was then that various groups angry with the shogunate for the concessions made to the various European countries found in the figure of the emperor an ally through whom they could oust the Tokugawa shogunate from power.

The slogan of that movement was Sonnō jōi (尊王攘夷 "Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians") and it finally succeeded in 1868, when imperial power was restored after centuries of being in the shadows of the country's political life.

Shogun Conception outside the country

China

During Ashikaga Yoshimitsu's rule, Japan and China resumed diplomatic relations, which had been broken because the first Ming emperor had established a policy of no relations with Japan. China's interest was in controlling Japanese pirate attacks (wakō) on its shores, an activity that affected its economy.

Yoshimitsu decided to take matters into his own hands and sent a diplomatic mission to China in 1401. In response, the Ming emperor invested Yoshimitsu with the title "King of Japan.

" The relationship between the shōgun and China was neither authorized nor consensual with the emperor of Japan, as Yoshimitsu never consulted him in matters of the country's foreign affairs, thus giving the impression to the countries in the area that he was the sole ruler of Japan.

In 1408 upon Yoshimitsu's death, the Ming emperor sent a diplomatic mission to offer his condolences to Yoshimochi and likewise to name him "King of Japan." Yoshimochi refused to accept the title or even to receive the diplomatic mission. Yoshimochi also decided to forget the issue of Japanese pirates, who again began to ravage the southern coast of China.

The Ming, in need of Japanese help to stop the pirates, kept trying their best to reestablish communication with the shōgun but it was impossible. It was not until the rule of Ashikaga Yoshinori that he agreed to receive envoys from China; in the year 1433 a diplomatic mission arrived on the shores of Japan carrying an imperial edict naming Yoshinori as "King of Japan.

" The title was later used by members of the Ashikaga shogunate in their communications with the Ming dynasty as in the case of the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa, who signed with that title a request for copper coins to the Chinese government due to the political and financial crisis the country was going through.

The last recorded use of the title "king of Japan" in documents between China and Japan by any shōgun was in 1547, used by Ashikaga Yoshiharu.

During the Japanese invasions of Korea the Ming attempted to appoint Toyotomi Hideyoshi as "King of Japan" with the aim of reaching a peace agreement. Hideyoshi refused such an appointment and when a number of demands were not granted, the war entered its second phase.

Shogun West

First contacts

In 1542, a Portuguese ship from China was blown off course in a storm, arriving in the territory described by Marco Polo as Cipango, which was virtually unknown throughout Europe. A year later Portuguese traders arrived on the shores of Japan seeking trade and with them came Jesuit missionaries in 1549 seeking to evangelize the country.

It was these missionaries who had the first contact with the Japanese authorities on the part of Europeans in 1559, when a group of them arrived in Kyoto. It was not until then that they realized that the country had two structures of authority: the imperial institution and the shogunate.

Because of the need to describe the nobles and authorities of the country, the missionaries found it necessary to use the noble titles recognized in Europe, such as "king", "prince", "marquis" or "duke", although these did not reflect the existing hierarchy. It is during this time that we find the term shōgun associated with "king," while daimyos were associated with the term "prince."

The situation changed in 1580-1590, when the Jesuits began to use the terms in the original language. This change is attributed to the arrival in Japan of Alessandro Valignano, a Jesuit visitor who used the original terminology in his letters.

The first publication to use the original terms of the Japanese hierarchical structure was Sumario de las cosas de Japón by Valignano, who in 1601 also wrote Libro primero del principio y progresso de la religión christiana en Japón, in which he reiterated the ambiguities and contradictions of using the European system of noble titles when applied to the Japanese case.

Another notable case was that of William Adams, an English navigator who was shipwrecked on the Dutch ship Liefde in April 1600. In his memoirs, Adams refers to Tokugawa as "the king of the whole country" and recounts how he was interrogated for several days by him about the political situation in Europe, about his religious beliefs and his differences with those of the Portuguese.

Williams made such a good impression on the shōgun (despite the intrigues of the Jesuit missionaries, who said that the English were the "bandits and robbers of all nations, " so they called for all the crewmen to be crucified as "enemies of Japan "), that Ieyasu allowed the crewmen of the Liefde to return home.

However, he kept him as a personal advisor in matters of international trade, appointed him samurai and hatamoto and provided him with a fief valued at 250 koku with 80 farmers. Williams died on May 16, 1620 in Hirado and never returned to his native country.

Another important attempt to bring the history of Japan and the mythical figure of the shōgun to Western audiences was that of Isaac Titsingh, a Dutch merchant representing the Dutch East India Company in Japan between 1779 and 1784.

Titsingh wrote three books relating to Japan and on this subject Illustrations of Japan; consisting of Private Memoirs and Anecdotes of the reigning dynasty of The Djogouns, or Sovereigns of Japan; a description of the Feasts and Ceremonies observed throughout the year at their Court; and of the Ceremonies customary at Marriages and Funerals:

to which are subjoined, observations on the legal suicide of the Japanese, remarks on their poetry, an explanation of their mode of reckoning time, particulars respecting the Dosia powder, the preface of a work by Confoutzee on filial piety, summarized as Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns in English, which briefly discusses the history of the Tokugawa shogunate government, with emphasis from Ietsuna to Ienari.

Titsigh died in 1812 and his work was published post mortem by two of his friends. Titsingh's work helped to better understand the role of the shōgun in the country's politics, as the shōgun was often referred to in Europe as "the emperor" while the emperor was considered a kind of "Japanese pope."

Shogun Today

Faced with the difficulty of explaining to an audience unfamiliar with Japanese history the functions or characteristics of the shōgun, Western terms continue to be used to describe him as "military dictator, " "generalissimo, " "feudal military administrator, "192 or simply "military governor. "

Shogun In popular culture

One of the major works that focuses attention on the figure of the shōgun is the novel Shogun: Lord of Samurai by writer James Clavell, which tells the story of Toranaga, a fictional figure based on the life of Tokugawa Ieyasu, months before the battle of Sekigahara, through the vision of an English navigator, whose exploits are loosely based on the life of William Adams.

The novel has been adapted into a television series and a Broadway musical.

Notable in video games is Shogun: Total War, which is set in the Sengoku period and deals with the attempts of seven daimyos to become shōgun.

Historian Stephen Turnbull served as historical consultant during its making. The sequel Total War: Shogun 2 adds around 30 or more clans, with the same goal of contesting the shogunate, and is a much more complete and impressive improvement on the previous title.

They were also used as a reference in 1995 in the third season of the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers television series, in which the shōgun inspired the Shōgunzords and the Shōgun-Megazord.