The word samurai (侍 samurai) or samuray is generally used to designate a wide variety of warriors in ancient Japan, although its true meaning is that of a military elite that ruled the country for hundreds of years.

The origin of the samurai dates from around the 10th century and was strengthened at the conclusion of the Genpei Wars at the end of the 13th century, when a military government was instituted under the figure of the shōgun, whereby the Emperor of Japan remained in his shadow as a mere spectator of the political situation of the country.

Its peak took place during the Sengoku period, a time of great instability and continuous power struggles between the various existing clans, which is why this stage of Japan's history is referred to as the "Warring States Period".

The military leadership of the country would continue to be in the hands of this elite until the institution of the Tokugawa shogunate in the 17th century by a powerful samurai landowner (known as daimyō) named Tokugawa Ieyasu,

who paradoxically, by becoming the highest authority when he was appointed as shōgun, fought to reduce the privileges and social status of the warrior class, a process that eventually culminated in its demise when the emperor resumed his role as ruler during the Meiji Restoration in the nineteenth century.

Historically, the image of a samurai was more closely related to that of an archer on horseback than to that of a swordsman, and it was not until relative peace reigned that the sword acquired the importance with which it is currently associated; the fantasy and reality of the samurai have been intermingled and idealized and their stories have served as the basis for novels, films, comics and even video games.

Samurai Etymology

Although there is no certainty as to the exact origin of the word samurai (侍), most historians agree that it has its origin in a variation of the Old Japanese verb saburau meaning "to serve," so that the derived term saburai becomes "those who serve. "

The earliest record that has been found of the word samurai dates from the eighth century and was not applied with a martial character, but was used to refer to domestic servants charged with caring for the elderly.

The word eventually derived to a military aspect and its meaning as we know it today emerged with the gunkimono (軍記物), a series of twelfth-century war histories through which the behavior, methodology, and appearance of the military elite have been studied.

The terms bushi (武士) and samurai (侍) have been used synonymously, but the difference is that the word bushi simply means "warrior " regardless of position or hierarchy, while the word samurai refers to members of a military elite.

Samurai History

Antecedents

Kofun Era

The Daisenryō-Kofun in Osaka, is the largest tomb of its kind and its construction dates to the 5th century AD.

During the Kofun period (250 - 530), the aristocratic class consisted of mounted warriors, who were buried along with their weapons, armor, bronze mirrors and jewelry in burial mounds that were usually in the shape of a keyhole. These burials were known as kofun (古墳 lit. "ancient tomb" or "ancient mound").

It was common to also deposit clay statuettes in the shapes of servants, animals and soldiers. These figurines were known as haniwa (埴輪) and replaced human sacrifices.

From the study of the haniwa found, it can be deduced that these aristocrats are the direct ancestors of what would later be known as samurai, a term that was not officially coined to refer to the elite warrior class until the 13th century.

During this period, Japan was intimately connected with the war situations in Korea and China. During the year 400, an infantry army came to the aid of the Paekche kingdom, but suffered a heavy defeat at the hands of the cavalry of the Koguryo kingdom.

This caused them to seriously rethink their war tactics. Although horses were already being used for field work in Japan, the training of these animals for warfare intensified, as did the training of horsemen. In 553, Paekche again sought the support of Japanese troops, but they requested archers and cavalry, a sign of the importance of these elements in the wars of the time.

Era Asuka

In 602, Prince Kume led an expedition to Korea accompanied by 120 to 150 local chieftains, each of whom held the title of Kuni ni Miyatsuko. Each was accompanied by a personal army, depending on the wealth of the fief. These troops constituted what would become the prototype of a samurai army centuries later.

War conflicts continued to occur in China and Korea. In 618 the Tang dynasty seized power in China and joined with the Korean kingdom of Silla in order to attack Paekche. The Japanese sent three expeditionary armies (in 661, 662 and 663) to aid the Paekche kingdom.

During these expeditions they suffered one of the worst defeats in their ancient history, losing 10,000 men and substantial ships and horses. Japan began to worry about an invasion by the new Silla-China alliance. In 670 a census of the population was ordered to recruit elements for the army.

In addition, the northern coast of Kyūshū was fortified, guards were posted, and beacons were built on the shores of Tsushima and Iki islands.

The Japanese forgot about foreign warfare upon the death of Emperor Tenji in 671. In 672 his two successors contested the throne in the Jinshin War. After Emperor Tenmu's triumph in 684, he ordered all civil and military officials to master the martial arts.

Emperor Tenmu's successors culminated in 702 the military reforms with the Taihō Code (大宝律令 Taihō-ritsuryō), by which a large and stable army conforming to the Chinese system was achieved. Each heishi (soldier) was assigned to a gundan (regiment) for part of the year and the rest was devoted to agricultural duties. Each soldier was equipped with bows, a quiver and a pair of swords.

Nara Era

With the birth of the Unified Silla State the threat of a Korean invasion of Japan disappeared, so the Nara Court turned its attention to the Emishi (蝦夷? "barbarians"), inhabitants of northern Japan with whom they had had numerous altercations.

In 774 a major revolt broke out, known as the Thirty-Eight Years' War, where the Emishi used a guerrilla warfare system and a curved-bladed sword, which performed better when mounted, as opposed to the straight sword of the Nara Court army. It was not until 796, through Sakanoue no Tamuramaro, that they finally managed to defeat them.

Sakanoue was given the title of Seii Taishōgun (征夷大将軍 "Great General Appeasing the Barbarians"), an expression that would later be used to designate the leader of the samurai.

The peasant enlistment system ended in 792, recognizing that the main military strength came from the chieftains and their soldiers and not from the peasants, who lacked adequate training and discipline for the battlefields.

This measure was reflected in the proclamation of an edict specifying that all kondei ("strong men") were to be purely warriors, not commoners. They were also to belong to the same lineage as the local landowners. The latter were to have two stable boys in their service.

Samurai in the Heian Era

By 860, most of the characteristics of the samurai can be seen: mounted horsemen skilled in the use of the bow, as well as the use of curved-bladed swords. These mounted warriors enjoyed the full confidence of the "Chrysanthemum Throne" and were responsible for the security of the cities, as well as quelling any revolts that occurred.

During the ninth century Japan suffered a serious economic decline as a result of plagues and various famines. At the beginning of the 10th century, numerous riots, disorders and rebellions occurred due to the situation.

The government took the decision to grant broad powers to local governors to recruit troops and act against the growing rebellions as they saw fit, which gave these governors enormous political power. It is during this period that the word "samurai," "those who serve," is first documented in a purely military context.

The first major test of the system's stability came in 935 with a revolt by Taira no Masakado, a descendant of Prince Takamochi, who had been sent by the imperial authority to quell the unrest in Kantō and was nicknamed "The Peacemaker. " At first the Heian court considered the Masakado incident to be just a local incident, until he went so far as to proclaim himself "new emperor."

Because of this, a provincial army was sent to put down his rebellion, and he was beheaded in 940. From this point on, due to their social background, these warrior leaders began to define themselves as a local aristocracy.

During this period, the lineages of greatest political importance were the Taira, the Fujiwara and the Minamoto. Minamoto no Yoriyoshi became involved in a major conflict of the time called the Zenkunen War or "war of the first nine years." This conflict lasted from 1051 to 1062, being the first war to be experienced in the country since the clashes against the Emishi.

The incident originated when Abe no Yoritoki, a descendant of the Emishi and a member of the Abe clan, failed to deliver the collected taxes to the court, so Yoriyoshi was sent to deal with him.

Yoriyoshi and Yoritoki had already reached a peaceful settlement, but an internal conflict broke out in the Abe clan and Yoritoki was killed. As a result, war was declared between Abe no Sadato, son of Yoritoki, and the Minamoto. It was not until 1062 that Yoriyoshi was able to defeat the Abe at the Battle of Kuriyagawa, carrying the rebel's head to Kyoto as a sign of triumph.

Minamoto no Yoshiie, son of Yoriyoshi, stood by his father's side throughout the conflict, gaining great prestige for his military prowess. This earned him the nickname Hachimantarō or "the first son born of Hachiman, god of war. "

During this period, the lineages of major political importance were the Taira, the Fujiwara and the Minamoto. Minamoto no Yoriyoshi was involved in a major conflict of the time called the Zenkunen War or "war of the first nine years". This conflict lasted from 1051 to 1062, being the first war to be experienced in the country since the clashes against the Emishi.

The incident originated when Abe no Yoritoki, a descendant of the Emishi and a member of the Abe clan, failed to deliver the collected taxes to the court, so Yoriyoshi was sent to deal with him.

Yoriyoshi and Yoritoki had already reached a peaceful settlement, but an internal conflict broke out in the Abe clan and Yoritoki was killed. As a result, war was declared between Abe no Sadato, son of Yoritoki, and the Minamoto. It was not until 1062 that Yoriyoshi was able to defeat the Abe at the Battle of Kuriyagawa, carrying the rebel's head to Kyoto as a sign of triumph.

Minamoto no Yoshiie, son of Yoriyoshi, stood by his father's side throughout the conflict, gaining great prestige for his military prowess. This earned him the nickname Hachimantarō or "the first son born of Hachiman, god of war. "

In the year of 1083 armed conflict would again break out involving the Minamoto, now in the Gosannen War or "war of the last three years," originating from differences between the leaders of the formerly allied Minamoto and Kiyowara clans.

After a fierce three-year contest in which the Court refused to help the Minamoto, the Minamoto were nevertheless finally victorious. When Yoshiie went to Kyoto to seek a reward, the court refused and even reproached him for the back taxes he owed, thus initiating a clear rift between the two.

Meanwhile, their rivals, the Taira were improving relations with them due to their exploits in the west of the country. The rivalry between the Minamoto and Taira clans was increasing and becoming more and more evident.

In 1156 a conflict took place between the two clans, when Minamoto no Yoshitomo joined Taira no Kiyomori against his father Minamoto no Tameyoshi and his brother Tametomo, during the Hōgen Rebellion. The battle was very brief, and in the end Tameyoshi was executed and Tametomo was punished by banishment.

In 1160, a new confrontation known as the Heiji Rebellion took place, where Yoshitomo clashed with Kiyomori. The victory of the Taira clan was so decisive that members of the Minamoto clan fled for their lives. The Taira pursued them and Yoshitomo was captured and executed.

Of the members of the original branch of the Minamoto family, only a few remained, being almost completely annihilated. In 1167 Taira Kiyomori received from the emperor the title of Daijō Daijin (Great Minister), which was the highest rank the emperor could bestow, making him the de facto ruler of the country.

Genpei Wars

The Genpei Wars were a series of civil wars fought again by the most influential clans in the country's political scene: the Taira and Minamoto. These wars took place between 1180 and 1185.35 In 1180, two separate rebellions broke out in the country by two different generations of the Minamoto clan: in Kyoto by the veteran Minamoto no Yorimasa and in Izu Province by the young Minamoto no Yoritomo.

Both revolts were put down with relative ease, on the one hand forcing Yoritomo to escape to Kantō, while Yorimasa was defeated at the Battle of Uji, where he committed seppuku before being captured.

After two years, during which both sides engaged in minor skirmishes, the Taira decided to take on Minamoto no Yoshinaka, Yoritomo's cousin, in 1512 - 1514, Yoshinaka defeated the Taira at the Battle of Kurikara and marched his army to where Yoritomo was. The armies of Yoshinaka and Yoritomo finally met at the Battle of Uji in 1184.

Yoshinaka lost the battle and tried to flee, but was overtaken at Awazu, where he was beheaded. With this victory, the main branch of the Minamoto would focus their efforts on defeating their main enemies: the Taira.

Yoshitsune led the clan's army on behalf of his older brother Yoritomo, who remained in Kamakura. Finally, at the Battle of Dan no Ura the Minamoto won the victory. Yoritomo considered his brother to be a threat and a rival, so his men pursued Yoshitsune until they defeated him during the Battle of Koromogawa in 1189, where the latter committed suicide.

In 1192 Minamoto no Yoritomo proclaimed himself shōgun, a title that until then had been temporary. This instituted the shogunate as a permanent figurehead, which would last for nearly 700 years until the Meiji Restoration. With the new figure of the shōgun, the emperor would become a mere spectator of the political and economic situation of the country, while the samurai would be the de facto governors.

Kamakura Shogunate

After only three shoguns of the Minamoto clan, the country again experienced civil war. The Hōjō clan had usurped the regency from the Minamoto. For this reason, in 1219 Emperor Go-Toba, seeking to restore the imperial power they enjoyed before the establishment of the shogunate, accused the Hōjō of outlawry.

Imperial troops were mobilized, giving rise to the Jōkyū War (1219 - 1221), which would culminate in the Third Battle of Uji. During this, the imperial troops were defeated and Emperor Go-Toba exiled. With Go-Toba's defeat, samurai rule over the country was confirmed.

Mongol invasions of Japan

After Kublai Khan claimed the title of Emperor of China, he decided to invade Japan with the purpose of bringing it under his rule. This would be the first time that the samurai could measure themselves against the forces of foreign enemies. On the other hand, the latter felt no interest in the traditional Japanese way of waging war.

The first invasion took place in 1274, when Mongol troops landed at Hataka (present-day Fukuoka). The sounds of drums, bells and war cries frightened away the samurai horses.

During this battle the Japanese troops were confronted with a very different technique in the use of the bow than they were accustomed to, as the Mongols shot at great distances and at the same time generated "clouds of arrows", unlike the solitary and close-range shots made by the Japanese archers.

Another major difference between the two forms of combat was the use of catapults by the Mongol army. During the night of the same day, a heavy storm inflicted severe damage on the invading fleet, so they decided to return to Korea to rearm their army.

After the withdrawal of the enemy army, the Japanese took a series of preventive measures, such as the construction of walls at vulnerable points along the coast, as well as the implementation of a guard.

The second invasion attempt took place in 1281. The samurai raided enemy ships from small rafts that could only carry twelve warriors in an attempt to prevent troops from landing on the coast. After a week of fighting, an imperial emissary was sent to ask Amaterasu, the sun goddess, to intercede on their behalf.

A typhoon swept away the Mongol fleet, which sank almost entirely. This event gave rise to the myth of the Kamikaze (神風 lit. "Divine Wind"), seen as a sign that Japan was the chosen of the gods and therefore they would see to its safety and survival. The few survivors decided to withdraw and thus the country would not face an invasion of major proportions again until several centuries later.

Kenmu Restoration

In the early 14th century, the Hōjō clan faced a new attempt at imperial restoration, now under Emperor Go-Daigo. When the Hōjō learned of this, they sent an army from Kamakura, but the emperor fled before they arrived, taking the imperial insignia with him. Emperor Go-Daigo sought refuge in Kasagi among warrior monks who welcomed him and prepared for a possible attack.

After attempts by the Hōjō to negotiate with Emperor Go-Daigo to abdicate and in the face of the latter's refusal, they decided to raise another member of the imperial family to the throne. However, because Go-Daigo had taken away the imperial insignia, they were unable to carry out the ceremony.

It is at this time that the figure of Kusunoki Masashige gained importance and renown, not only for his military prowess, but also for the unconditional support he gave to the emperor. This example would later serve as a reference and model for future samurai.

Masashige fought for Emperor Go-Daigo from a yamashiro (mountain castle). Although his army was not very numerous, the orography of the place provided an extraordinary defense. The castle finally fell in 1331, so Masashige decided to flee and then continue the fight. The emperor was captured and taken to the Hōjō headquarters located in Kyoto and later exiled to the islands of Oki.

The Hōjō tried to finish off the army led by Masashige, who built another castle in Chihaya with even better defenses than the previous one, so the Hōjō were immobilized. Masashige's staunch defense prompted Go-Daigo to return to the scene again in 1333.50 When the Hōjō learned of his return, they sent one of their top generals, Ashikaga Takauji, in pursuit.

Ashikaga thought at the time that it would be more beneficial for him and his clan to ally with the emperor's side. For this reason, he decided to launch his army's attack on the Hōjō headquarters at Rokuhara.

The blow received by Ashikaga's treachery had serious consequences for the regents, their army being severely depleted. The power of the Hōjō clan was finally extinguished that same year of 1333, when a warrior named Nitta Yoshisada joined the imperial supporters and increased their forces. Nitta and his army headed for Kamakura and defeated the Hōjō.

Ashikaga Shogunate

After helping the emperor return to the throne, Ashikaga Takauji expected to receive a large reward for his services. However, because he felt that what was offered was not enough, he decided to rebel. The Ashikaga were descendants of the Minamoto clan, so they could accede to the imperial throne.

For this reason, the emperor decided to act quickly and sent an army against Takauji, following him all the way to Kyūshū. Takauji was not defeated and returned to the scene in 1336. The emperor sent Masashige to confront the rebel troops at Minatogawa (now Kobe), resulting in a decisive victory for Takauji.

Faced with this situation, Masashige decided to commit seppuku. At this point the shōgun appointed his own emperor, so that for the next fifty years there would be two imperial courts: the Southern Court in Yoshino and the Northern Court in Kyoto. This conflict would become known as Nanbokuchō (南北朝 literally, "Southern and Northern Courts").

It was not until 1392 and thanks to the diplomatic skills of one of the greatest rulers in Japanese history, the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, that the two lineages were reconciled. Yoshimitsu was also a great promoter of the arts. This was reflected in the Kinkaku-ji (金閣寺 Temple of the Golden Pavilion), which he ordered to be built during his rule.

Sengoku Period

After a brief period of relative stability, a political vacuum was created during the shogunate of Ashikaga Yoshimasa, grandson of the famous Ashikaga Yoshimitsu. Yoshimasa used to devote all his time to artistic and cultural matters, so he completely neglected the economic and political situation of the country.

Because of this, opportunistic landowners began an internal struggle for power and land, taking for themselves the title of daimyō (大名 lit. "great surnames"). This period in Japanese history, from 1467 to 1568, is known as the Sengoku period (戦国時代, Sengoku jidai) or "period of warring states." It is precisely under this climate of instability and armed conflict that the samurai have their greatest involvement.

Among the most important figures of this period are Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin, whose legendary rivalry has served as inspiration for several literary works. The armies of Shingen and Kenshin clashed in the well-known Battles of Kawanakajima. Although some of these were mere skirmishes, the Fourth Battle of Kawanakajima was of great importance.

With this unbridled infighting in the pursuit of more power and land, it was only a matter of time before some powerful daimyō attempted to reach Kyoto to seek to overthrow the shōgun, which happened in 1560. Imagawa Yoshimoto marched to the capital accompanied by a large army with the aim of overthrowing the then ruler.

However, he did not count on facing the troops of Oda Nobunaga, a secondary daimyō whom he outnumbered twelve to one in the number of soldiers. Yoshimoto, confident of his military might, used to celebrate victory even before the battle was over.

Oda Nobunaga managed to attack him unawares during one of his famous celebrations at the Battle of Okehazama. When Yoshitomo left his tent due to the uproar, he was caught and killed on the spot.

Nobunaga then went from a minor character to a prominent figure of the period. In 1568 Nobunaga marched into Kyoto and dismissed the shōgun. This marked the beginning of what is known as the Azuchi-Momoyama period.

Azuchi-Momoyama period

Oda Nobunaga was famous for introducing and training ashigaru (足軽 light-footed) soldiers in the use of arquebuses. This would radically change the way warfare was conducted in Japan.

The most representative battle is the Battle of Nagashino, in which Oda's forces defeated the legendary and feared cavalry of the Takeda clan through the use of firearms. From this point on its use became typical on the battlefield and was considered a vital factor in obtaining victory.

Nobunaga was very close to unifying the country, but in 1582 he was betrayed by one of his top generals, Akechi Mitsuhide, and forced to commit seppuku at the Honnō temple. This event is known as the "Honnō-ji Incident".

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, another of Nobunaga's top generals, avenged his lord's death by defeating Mitsuhide during the Battle of Yamasaki, rising with the authority of the late Nobunaga. After the Battle of Shizugatake, Toyotomi continued with the task of unifying the country. However, due to his humble origins, he was never able to be appointed with the title of shōgun.

The figure of the samurai is defined

It was Hideyoshi who finally defined the figure of the samurai, as he ordered and defined the guidelines for the training, discipline and specialization of the country's soldiers. The ashigaru soldiers were trained in the use of both the naginata and the arquebus.

An edict proclaimed in 1588, known as the "sword hunt," sought to formally separate soldiers and samurai from peasants, whereby their weapons were confiscated. Another edict of 1591 completed the separation and distinction between the social classes of samurai and peasants.

Unlike the historical type of recruitment in the past, where the peasants took up arms for some periods of the year and the rest of the year was dedicated to their work in the fields, the specialization of the members of the army was emphasized.

Tokugawa Shogunato

Before his death, Hideyoshi had appointed the "Council of Five Regents" in order for them to rule upon his death and until his son Hideyori was old enough to take over the country. Tokugawa Ieyasu had served first under Oda Nobunaga and then under Hideyoshi himself.

He had also been appointed as one of the "five regents". This character began to dispute the government for himself, which culminated in the Battle of Sekigahara. In this event, Tokugawa and his "Army of the East" were victorious. Tokugawa was a descendant of the Minamoto clan, so he was appointed as shōgun in 1603 by Emperor Go-Yōzei.

Siege of Osaka

The last real threat to Ieyas al to Ieyasu's rule was the figure of Toyotomi Hideyori, who was now a young daimyō occupying Osaka Castle. Many samurai who opposed Ieyasu rallied around Hideyori claiming that he was the rightful ruler of the country. Ieyasu ordered him to leave the castle, so he began to recruit supporters.

The Tokugawa, under the leadership of the Ōgosho (大御所 shōgun cloistered) Ieyasu and the shōgun Hidetada led a large army to the castle in what became known as "The Osaka Winter Campaign". The siege began on November 19, when Ieyasu led three thousand men across the Kizu River, destroying the fort there.

A week later, he attacked the town of Imafuku with 1500 men, against a defense force of 600. With the help of a squad equipped with arquebuses, the shogunal forces won another victory. Other small forts and villages were attacked before the siege of Osaka Castle itself began on December 4.

Sanada-maru was an enclave defended by Sanada Yukimura and 7,000 men, aligned with the Toyotomi. The shōgun's armies were repeatedly repulsed, and Sanada and his men launched a large number of attacks against the siege lines, breaking them three times. Ieyasu then resorted to artillery, bringing 300 cannon, along with other men to dig under the walls.

On January 22, the winter siege ended. Toyotomi Hideyori made an appeal to prevent a rebellion and agreed to have the castle moat filled in and the outer walls torn down.

After Hideyori began to re-dig the castle moat, the castle was besieged, in what became known as the "Summer Siege of Osaka." Finally, after the decisive Battle of Tennōji in 1615, the castle fell to the Tokugawa army and the defenders were killed, including Sanada Yukimura, Hideyori, his mother Yodogimi, and Kinimatsu, Hideyori's son who was only eight years old.

Hideyori's wife Senhime (Ieyasu's granddaughter) was safely returned to her family. With the Toyotomi finally exterminated, there was no longer any threat to the Tokugawa domination of Japan. It was precisely this battle that was the last in which Ieyasu would actively participate.

Measures against the samurai

From the time Ieyasu established the Tokugawa shogunate, he initiated a process to remove the social and legal status of the samurai class. Similarly, he established the social class of ashigaru soldiers as a lower rank than that of the samurai.

During this period most samurai lost direct possession of land and were faced with two choices: lay down their arms and become peasants or move to the main town of their fief and become paid servants of the daimyō. Only a few samurai remained in the northern outer provinces as direct vassals of the shōgun. These samurai were known as "the 5000 hatamoto".

In 1650, the shogunate issued a law prohibiting duels between samurai. In 1690, the practice of the various martial arts was formally banned. At this time, skills and training in the use of the bow, spear, sword and hand-to-hand combat suffered a sharp decline.

With the measures taken by the government, many samurai turned to farming and craft making. Some became rōnin (浪人 lit. "wave man"), i.e., samurai without a lord. Many others embarked on trafficking, smuggling, and stealing goods in the ports and on the high seas, which also ended in the year of 163972 with the "Closed Borders" edict.

This edict sought to control and avoid the influence of foreigners, especially Catholic missionaries, considered by the government as "subversive".

Meiji Restoration

The compulsory opening of trade that Japan underwent after Commodore Perry appeared in Edo Bay in 1853 upended the political situation in the country. Various nationalist groups began to put pressure on the government in an effort to keep foreigners out of the country.

The slogan Sonnō jōi (尊王攘夷 "Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians") became a political movement to overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate under the pretext of exacting revenge for its "lukewarm" response to the "foreign threat."

For the first time in many centuries, the emperor of Japan, under the figure of Emperor Kōmei, took a leading role in national politics, and was joined by various groups of samurai who had been relegated from the political spheres. Pressure within the country led the shōgun to make the decision to break off relations with foreigners.

This led to the assassination of several merchants from European countries and consequently triggered a series of hostilities, such as the bombing of Shimonoseki.

The deaths of both the emperor and the shōgun were virtually simultaneous. The late shōgun Tokugawa Iemochi's successor, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, took office in mid-1866. Meanwhile, Mutsuhito, the second son of Emperor Kōmei, who died in 1867, became the new Meiji Emperor.

Yoshinobu tried in vain to make the necessary adjustments to avoid a clear confrontation with the pro-imperialist forces, which counted the Chōsu and Satsuma clans as leaders. However, as the possibility of internal conflict increased, he decided to resign in 1868. This ended the bakufu or Tokugawa shogunate.

Forces seeking to reestablish the figure of the shōgun took up arms, so a civil war known as the Boshin War took place between 1868 and 1869. Again, both samurai and rōnin made their appearance on one side and the other, until finally the pro-imperialist forces rose to victory.

With the war won, the Meiji Emperor began to modernize the country. Foreign trade was reopened, armaments and ships were purchased, and the army organization of the European powers was copied. The privileges of the samurai class were abolished, so the nationalists, who had originally supported the emperor's figure as well as the Sonnō jōi philosophy, felt betrayed.

The Last Samurai

Such abrupt and massive changes in Japanese culture, as in the case of dress, appeared to the samurai as a betrayal of the jōi, part of the Sonnō jōi, which had served to justify the expulsion of the Tokugawa shogunate. Saigō Takamori, one of the most senior leaders in the Meiji government, was particularly concerned about the growing political corruption.

After a series of differences with the government, he resigned his position and retired to the Satsuma domain. There he established academies where all students took training and instruction in war tactics.

News about Saigō's academies was received with great concern in Tokyo. The government had just faced some small but violent samurai revolts in Kyūshū, and the number of supporters it had in the Satsuma region was alarming.

On February 12, 1877, Saigō met with his landlords Kirino Toshiaki and Shinohara Kunimoto and announced his intention to march to Tokyo for talks with the government. His troops began to advance, and by February 14 the advance party arrived in Kumamoto Prefecture.

General Tani Tateki, commander of Kumamoto Castle, had 3,800 soldiers and 600 policemen at his disposal. Since many of his men were from Kyūshū and many in turn originally from Kagoshima (Saigō's hometown), he decided not to risk defections or betrayals and remained on the defensive.

On February 19 at 1315 hours, the first shots were fired by the castle defenders as Satsuma units attempted to force their way into the castle. On February 22, the main Satsuma armada arrived and attacked Kumamoto Castle in a pincer movement. The battle continued into the night and the imperial forces that had come out to meet them retreated.

Even with the triumph, Satsuma's army was unable to take the castle and they realized that the conscripts that made up the imperial forces were not as inefficient as they had first assumed. After two days of unsuccessful attack, Satsuma's forces dug in around the castle and tried to besiege it.

During the siege, many of Kumamoto's former samurai defected to Saigō's side, swelling his forces to around 20,000 men. Meanwhile, on March 9, Saigō, Kirino and Shinohara were stripped of their official positions and titles from Tokyo. However, Saigō argued that he was not a traitor, but only sought to rid the emperor of the bad influences of misguided and corrupt advisors.

The main contingent of the Imperial Navy, under General Kuroda Kiyotaka and assisted by General Yamakawa Hiroshi, arrived in Kumamoto in aid of the castle occupiers on April 12. This caused Satsuma's troops, who were now at a complete numerical disadvantage, to flee.

After constant pursuit, Saigō and his remaining samurai were pushed back to Kagoshima, where the final battle would take place: the Battle of Shiroyama. Imperial Army troops commanded by General Yamagata Aritomo and marines commanded by Admiral Kawamura Sumiyoshi outnumbered Saigō's forces sixty to one.

Imperial troops spent seven days building and elaborate systems of dams, walls and obstacles to prevent them from escaping. Five warships joined Yamagata's artillery power and reduced the rebels' positions. After Saigō rejected a letter requesting their surrender, Yamagata ordered a frontal attack on September 24, 1877. By 6 a.m., only 40 rebels were still alive and Saigō was mortally wounded.

His followers claim that one of them, Beppu Shinsuke acted as kaishakunin and helped Saigō commit seppuku before he could be captured. After Saigō's death, Beppu and the last samurai standing raised their swords and headed downhill toward the imperial positions, until the last of them fell by Gatling machine gun fire. With these deaths, the Satsuma rebellion came to an end.

Saigō Takamori was labeled a "tragic hero" by the people on February 22, 1889, and the Meiji Emperor pardoned Saigō post mortem in 1891. He is now considered by some historians as the true last samurai.

Samurai Structure

Family ties as well as the loyalty of vassals to the daimyō were extremely strong, and it was these factors that governed the structure of a samurai army. Anyone born into a warrior household was trained from childhood in order to become a worthy representative of his ancestors.

On the other hand, alliances between clans represented the weakest ties, and throughout history there were repeated episodes where a clan betrayed its "ally" at the very moment of battle.

Until the mid-16th century, the common organization of a samurai army was much the same: at the end of the campaigns, the army was disbanded and the vast majority of ashigaru and some samurai returned to their work in the fields.

It was not until the Sengoku period that some daimyō with sufficient resources maintained a stable army and sought a degree of specialization in the military, including infantry.

The hierarchical structure depended on factors such as birth, lifetime vassalage, and social and military aspects. At the apex of the pyramid were the daimyō and next to them their close relatives and family; next were the lifetime retainers of the family, who served their lord for many years; the next rung were the vassals, whether they had joined their service or were forced after the defeat of their former lords.

The ashigaru of the Sengoku period were in the last echelon and were divided into three sections according to the weapon they wielded, whether arquebuses, spears or bows. There were also ashigaru dedicated to serving the various samurai, others were standard-bearers, and some others were assigned to drummers.

Recruitment

During much of the Sengoku period, every samurai was expected to be ready to present himself on the battlefield with his weapons, armor and horse in the event of conflict. In addition, each samurai was expected to provide troops in the service of his lord in accordance with the wealth of the fief to which he belonged.

Thus, the recruitment of the necessary troops fell to the samurai. The latter took with them other samurai or day laborers who left their lands to become ashigaru.

When the army was to be assembled, they were notified of the date and place of review. Each ashigaru would gather his weapons and armor and wait for the sounding of the horagai (shell trumpet), drum or bells, which would signal the time to depart.

Upon arrival at the agreed point, the samurai would review them. From that point they would march together to report to the castle and join the rest of the army.

Japanese castle

One aspect of vital importance throughout the history of the samurai was castles. Early fortifications in Japan were hardly what people associate with "castles," as they were made almost exclusively of wood.

They relied much more on the natural defenses and topography of the site (such as rivers, ponds, etc.) than any man-made elements, and were preferred to be placed on top of mountains.

These types of constructions, known as kōgoishi and chiyashi, were not built with the long term in mind, so the natives of the archipelago built these fortifications and they were later abandoned.

The inhabitants of Yamato began to build towns at the beginning of the 7th century, expanding the palace complex, surrounded on all four sides by walls and impressive gates.

Wooden fortifications were built throughout the country to defend the territory from the Emishi, Ainu and other groups. Unlike their predecessors, these constructions were relatively more durable and were built during times of peace.

Towards the end of the Heian period the rise of the samurai class drastically influenced the construction of castles. This was because their position was no longer only planned with the idea of defending the national territory from external attacks, but because from that time on, the different clans had to take care of each other.

The beginnings of the form and style of what are today considered "classic" stereotypes of Japanese castles emerged at this time. The so-called jōkamachi (城下町 lit. "village under castle") also appeared, grew and developed.

Despite advances in construction, most castles of the period remained in the same form as the wooden fortifications of centuries earlier, only longer and a bit more complex.

Similarly, they sought to be located high in the mountains, so these types of castles are known as yamashiro (山城 "mountain castle"). It was not until the last 30 years of this wartime period that drastic changes would develop.

Unlike in Europe, where the spread of the use of cannons ended the era of castles, in Japan, the introduction of firearms, ironically, was an incentive for their improvement and development.

Azuchi Castle, whose construction was completed in 1576 was the first example of the new type of castles. These new buildings were built larger and placed on a large stone base known as musha-gaeshi (武者返し). Thanks to these bases the castles better withstood Japan's usual earthquakes.

They were also designed with a concentric arrangement and also featured a central high tower. Additionally, the castles began to be built on flat sites rather than densely forested mountains.

Such was the importance of these new castles that both Hideyoshi's Fushimi-Momoyama Castle and Nobunaga's Azuchi Castle lent their name to this short period - the Azuchi-Momoyama period - during which this type of castle for military use flourished.

When siege weapons were used in Japan, they were most often Chinese-style blunderbusses or catapults and were used almost exclusively as anti-personnel weapons. There are no records of the goal of destroying the walls being set, and in fact it was seen as "more honorable" and more tactically advantageous for the defender to come out of the castle to fight the battle.

When battles were not resolved in this way, efforts boiled down to preventing the castle from receiving supplies. This could last for years, which involved surrounding the castle with a large enough force until surrender was obtained.

An example of this was Nobunaga's siege of the castle guarded by the Ikko Ikki, a class of warrior monks who endured no less than eleven years of constant attack.

Azuchi Castle was destroyed ten years after the completion of its construction, but a new period in the way castles were built began. Among the castles built in subsequent years was Hideyoshi's Osaka Castle, completed in 1583. It incorporated the new features and construction philosophy of Azuchi Castle, although larger, better placed and stronger.

Some powerful families controlled not just one castle, but a series of castles, where the main castle was called honjō and the satellite castles shijō. Although the shijō were generally castles in the full sense of the word, they were often wooden or earthen constructions.

Usually, fire beacons, taiko drums or seashells were used to establish communications between castles over great distances. The Hōjō family's Odawara Castle and its network of satellites was one of the most powerful examples of the honjō-shijō system; the Hōjō controlled so much land that a hierarchy of sub-satellites had to be created.

The castles of the Edo period became luxurious residences for the daimyō and their families. They also served to protect them against internal insurgencies or uprisings by villagers. To counter the might of the daimyō, the Tokugawa shogunate decreed a series of regulations limiting the number of castles to one per han, with few exceptions, thereby halting their construction.

Throughout history many castles would be destroyed, either as part of the Meiji Restoration or during the bombings of World War II. In fact, very few of today's Japanese castles are the originals and castles rebuilt with steel and concrete in modern times predominate.

When the Tokugawa shogunate enacted the edict of sankin kotai or "Alternate Presence," it was stipulated that the wives and children of each daimyō were to remain in yashiki (屋敷 manor house).

The latter were located in the vicinity of Edo Castle, and their proximity was governed by the rank of each family; those of higher rank and trust were located closer to the castle. This system of yashiki was soon adopted by the daimyō themselves in their respective province, under the same system.

Samurai Armor and clothing

Armor

The earliest armor, found through excavations in the kofun, was given the name tankō (鍛鋼). They were made of solid iron, the armor plates were attached to each other with leather straps and were specifically designed to be worn while standing.

To protect the lower body, warriors wore a flared skirt called a kusazuri. The shoulders and forearms were covered with curved plates that reached to the elbow. From those times, the metal surface was covered with laminate lacquer to protect it from the weather, as it would continue to be applied to later models.

The particular feature of the helmet was that part of the front was shaped like a visor, in addition to iron teeth at the top whose purpose was to hold pheasant feathers. Later a type of lamellar armor was designed, which is known by the name keikō (携行), from which in turn the yoroi style (鎧), which is the classic samurai armor, was derived.

Because if the armor was made entirely of iron it had a considerable weight, pieces of that metal were only used in the areas where more protection was required and in the rest of the armor pieces of iron were alternated with leather. On average, a yoroi weighed approximately 30 kilograms and provided good protection.

The armor covering the body was called do and formed the basis of this defensive clothing. Over the centuries there was a tendency to replace the yoroi with an armor called do-maru.

The latter emerged as the evolution of the armor of infantrymen, much simpler and more comfortable when fighting in the field. The armor developed in the sixteenth century is known as tōsei gusoku (当世具足) or "modern armor". Its characteristic feature is that it had added protections for the face, thigh and a sashimono, which was a small banner on the back.

Clothing

On the battlefield

Underneath the armor or their own clothing, the undergarments worn by samurai were known as fundoshi (褌), which was a kind of loincloth made of linen or cotton.98 On the battlefield, samurai wore socks known as tabi, strappy sandals called waraji or zori, and sometimes a pair of geta (clog-like shoes).

The first section they wore were suneate (脛当て) or shin guards, in addition to haidate or thigh guards. The latter became famous until the Sengoku period, when kusazuri (antemusle guards) were reduced.

Gloves called yugake were also worn, along with kote (小手 sleeves), to protect arms and hands. An uwaobi (上帯) - or outer belt - held the whole ensemble of clothing and armor together. A nodowa was used to protect his neck. In addition, a hachimaki (鉢巻き) was placed around the head to receive the weight of the kabuto (兜 helmet).

Some samurai were accustomed to wearing some form of masks to protect the face, which were known as hoate. These could be full or half masks that protected even below the eyes, and may or may not include a nose piece.

High-ranking samurai also tended to wear a jinbaori (陣羽織 overalls) that was placed over the armor. These were not usually worn in combat, but were worn inside the camp to give a ceremonial touch to the gathering, as well as to reflect the importance of the personage wearing it.

Normal clothing

The final evolution of armor took place during the Edo period when wars ceased and armor then became luxurious gifts and was only worn in castles. The typical attire was the hakama and kimono, while for more formal occasions they wore a jacket over the hakama called kataginu, which combined were known as kamishimo.

When faced with situations of utmost importance, such as an interview with the shōgun, a daimyō would be expected to wear a nagabakama, extremely long pants that dragged on the floor.

Samurai Weapons

Cutting blade

The nihontō, more commonly known in the West as the katana, is the weapon most closely associated with the samurai and was even considered during the Edo period to be "the soul of the samurai."

A samurai never abandoned his sword, even in times of peace. The best gift a samurai could receive from his daimyō was a sword forged by a celebrated master. However, it is worth noting that for most of Japanese history, the main weapons were the bow and spear. It was not until the wars ended that the sword acquired the fame it has today.

The first swords used by Yamato soldiers were straight, some with a bulbous hilt and were known as "mallet-headed swords." Some others, such as the so-called "Korean swords," had a hilt in the shape of a ring ending with the silhouette of an animal. These weapons averaged 90 centimeters in length.

The tachi was the classic samurai sword and hung with the blade downward. This type of sword had to be wielded with both hands, so the bow had to be left behind to use it. Later the katana was successfully developed, which, together with the wakizashi, were known as daishō (大小 lit. "big and small").

When a samurai wore his full armor, the katana hung with the blade downward and the wakizashi was sometimes replaced by a tantō, which came to be considered one of the most important weapons on the battlefield.

It was said that a good sword had to be capable of two things: cutting seven bodies stacked on top of each other and be sharp enough that when dipped in water it could cut a water lily floating on the surface.

The impressive strength of the katana was due to its curvature, which made it possible for the cut produced to even sever the opponent's bone. Since it had to be wielded with both hands, the sword bearer had to stand at right angles to the enemy.

The samurai did not use a shield for protection, since the katana was a defensive and offensive weapon at the same time. Because of its great strength, it could strike the opponent's weapon to deflect the attack and then deliver a killing blow.

Because of all these characteristics, it is no exaggeration for many historians to claim that the katana is far superior to swords designed by other cultures.

Another type of sword developed was the nodachi, known as the "field sword. " It had an extra-long blade and appeared in the early sixteenth century.

There are few records that this weapon was actually used on the battlefield, since, due to its great weight, the bearer had to have great physical strength to wield it while standing, even more so if it was carried while riding. Most records document that this type of sword was created for the purpose of serving as offerings to shrines and temples.

The naginata (a type of bow) is the weapon most often cited in samurai chronicles. It consisted of a curved blade mounted on a wooden handle and resembled Chinese halberds in appearance.

The naginata was an extremely versatile weapon, as it could be used to strike, stab or slash the enemy. The sōhei, a class of warrior monks, were recognized for the degree of specialization they achieved in wielding it.

Another recurrent weapon was the yari, a kind of Japanese spear that appeared as the weapon used by infantry troops during the 15th century. A type of yari, known as mochi yari, also became part of the samurai arsenal.

Projectiles

For most of the history of the samurai, the Japanese bow (called yumi) was their weapon of choice and only the sword was usually resorted to when descending from horseback and engaging in hand-to-hand combat. Samurai were usually skilled in the kyūba no michi "way of the bow and horse. "

The bows used at that time largely resemble those used today in kyūdō. The bow had to be raised to the height of the rider's head in order to shoot properly. The practice of horse and bow gave rise to yabusame, which is practiced to this day.

The technique of using the bow on horseback required a lot of practice, as it could only be shot from the rider's left side and had a shooting angle of 45º. This was further complicated if the rider wore armor. During the Sengoku period archery was combined with the use of ashigaru arquebusiers.

During 1510, samurai were introduced to the metal cannon115 and in the same year, Hōjō Ujimasa purchased a Chinese pistol.116 By 1548, during the Battle of Uedahara, the use of firearms was recorded, so that in one form or another their use had spread among the various clans. In 1543, Portuguese merchants arrived in Japan seeking commercial exchange.

Among the items they exchanged were European arquebuses. From 1549, various craftsmen developed the necessary technique to reproduce these weapons118 and began to manufacture Japanese arquebuses called Teppō (鉄砲 lit. "steel cannon").

By 1553 Oda Nobunaga's army already had 500 arquebusiers, which would show their effectiveness with appropriate tactics such as circular shots used in the battle of Nagashino.

Although many samurai opposed its implementation because with these new conditions any soldier was in a position to kill a trained and skilled martial arts master (even if he was a lowly ashigaru) with a single shot, its implementation spread throughout the country and became a typical element in war conflicts.

It should be noted that the use of large cannons did not spread or cause the same emotional impact that was experienced with the results of firearms. There are several records that mention the use of small cannons that were obtained from European ships adapted for use on the battlefield.

However, because the tactics of warfare did not consist in the demolition of fortresses, but rather in siege and open field fighting, techniques were not developed to produce cannons of large dimensions.

Samurai Combat techniques

Depiction of Onikojima Yatarō Kazutada with the severed head of an enemy in his hand, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

During the existence of the samurai, two opposing types of organization reigned.

The first type was conscript-based armies: at the beginning, during the Nara period, samurai armies were based on conscript armies of the Chinese type and towards the end on infantry units composed of ashigaru. The second type of organization was that of mounted samurai who fought individually or in small groups.

At the beginning of the contest a series of bulb-headed arrows were fired, which whizzed through the air. The object of these shots was to call the kami to witness the displays of bravery that were about to unfold. After a brief exchange of arrows between one side and the other, a contest called ikkiuchi (一騎討ち) would ensue, where great rivals from one side and the other would clash.

Such duels were greatly influenced by aspects such as rank, name, position within the army, etc. After these individual combats, the major battles took place, generally with infantry troops led by mounted samurai. At the beginning of samurai battles, it was an honor to be the first to enter battle.

This changed in the Sengoku period with the introduction of the arquebus. At the beginning of the use of firearms, the methodology of combat was as follows: at the beginning there was an exchange of arquebus shots at a distance of about 100 meters;

when the time was right, the ashigaru spearmen were ordered to advance and finally the samurai would attack, either on foot or on horseback. The army chief was usually seated on a scissor chair inside a semi-open tent called a maku, which displayed his respective mon.

As a sign of the strong symbolism this represented, another way of calling the shogunate instituted by Minamoto Yoritomo was the term bakufu, which meant "rule from the maku. "

In the midst of the fray, some samurai would decide to get off their horses and seek to cut off the head of a worthy opponent. This act was considered an honor. Moreover, by doing so, they gained respect among the military class. After the battle, high-ranking samurai usually held a tea ceremony, and the victorious general would review the severed heads of the enemy's most important members.

It is important to note that most battles were not resolved in the idealistic manner outlined above, but rather most wars were won by surprise attacks, such as night raids, fires, etc. The renowned samurai Minamoto no Tamemoto asserted:

According to my experience, there is nothing more advantageous in crushing the enemy than a night attack [...]. If we set fire to three sides and close off the fourth, those fleeing from the flames will be shot down by arrows, and those seeking to escape from the flames will not be able to flee from the flames.

Minamoto Tamemoto.

Collecting heads

Cutting off the head of a worthy rival on the battlefield was a source of great pride and recognition. There was a ritual to beautify the severed heads: first they were washed and combed and then the teeth were blackened by applying a dye called ohaguro.

The reason for blackening the teeth was that white teeth were a sign of distinction, so applying a dye to darken them was a metaphorical way of taking away some of it. Finally the heads were carefully arranged on a board for display.

During Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea, such was the number of severed enemy heads that had to be sent to Japan, that for logistical reasons only the nose was sent. These were covered with salt and shipped in wooden barrels. These barrels were buried in a burial mound near Hideyoshi's "Big Buddha," where they remain to this day under the misnomer of Mimizuka or "ear mound. "

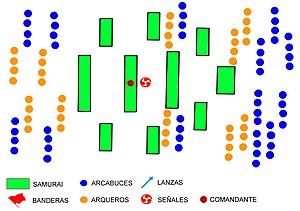

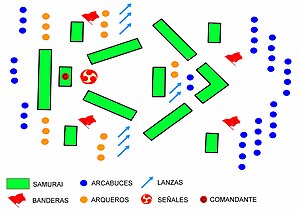

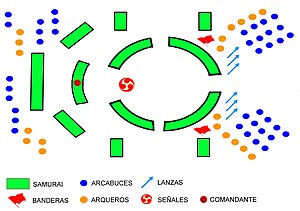

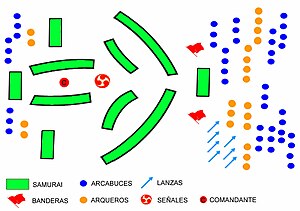

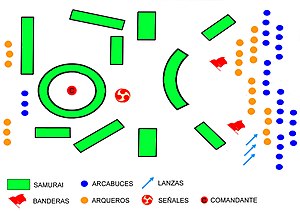

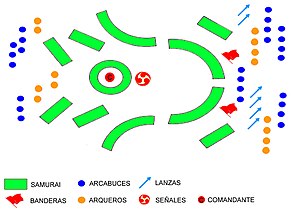

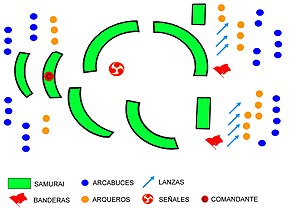

Samurai Military formations

During the Azuchi-Momoyama period and thanks to the introduction of firearms, combat tactics changed drastically. The military formations adopted had poetic names, among which the following stand out:

- Ganko (birds in flight) - This was a very flexible formation that allowed the troops to adjust depending on the opponent's movements. The commander was located in the rear, but close to the center to avoid problems with communication.

- Hoshi (arrowhead) - This was an aggressive formation in which the samurai took advantage of casualties caused by ashigaru fire. The signaling elements were close to the commander's main generals.

- Saku (bolt) - This formation was considered the best defense against the Hoshi formation, as two lines of arquebusiers and two lines of archers were in position to receive the attack.

- Kakuyoku (crane wings) - Recurring formation with the purpose of surrounding the enemy. The archers and arquebusiers would thin out the enemy troops before the melee attack of the samurai while the second company would surround them.

- Koyaku (yoke) - Named after the yokes used on oxen. It was used to neutralize the attack "crane wings" and "arrowhead" and its purpose was for the vanguard to absorb the first attack and give time for the enemy to reveal his next move to which the second company could react in time.

- Gyōrin (fish scales) - This was often used to deal with much larger armies. Its purpose was to attack a single sector to break the enemy ranks.

- Engetsu (crescent) - Formation used when the army was not yet defeated but an orderly retreat to the castle was needed. While the rearguard retreated, the vanguard could still organize itself according to the circumstances.

Samurai Martial arts

Every child growing up in a samurai family was expected to grow up to be a warrior, so much of his childhood was spent practicing various martial arts. A complete samurai had to be skilled at least in the use of the sword (kenjutsu), the bow and arrow (kyujutsu), the spear (sojutsu, yarijutsu), the halberd (naginatajutsu) and later firearms.

Likewise, they were instructed in the use of these weapons while riding horses. They were also expected to know how to swim and dive.

During Japan's feudal era, various types of martial arts flourished, known in Japanese as bujutsu (武術). The term jutsu can be translated as "method," "art," or "technique " and the name possessed by each is indicative of the mode or weapon with which they are executed. The combat methods that were developed and perfected are very diverse.

Samurai Philosophy and culture

Bushidō

During long periods of instability, the samurai were confronted day by day with the horrors of war and the possibility of their own death, so they were most certainly all aware of that risk.

The classical precepts of bushidō (武士道 lit. "Way of the warrior ") first appeared compiled in a breviary known as Hagakure in the early eighteenth century. It contained some practical advice applicable to samurai behavior, and the theme of death is of central importance in the work.

The main difference between bushidō and European chivalry is that, in the former, there is a total absence of courtly love. When women do make an appearance in heroic samurai stories, it is usually as a response of self-immolation, as when they committed suicide because the castle in which they were staying fell into enemy hands.

The major dogma of the bushidō lay in the aspect of reinforcing the samurai's idea of themselves as members of an elite superior to the rest of society. They used to refer to ashigaru as "their inferiors " and foreigners as "barbarians. "

The bushidō furthermore encouraged leaders-even those of the country-to participate in armed conflicts. Every commander was supposed to remain on a scissors stool in the rear throughout the battle, and many even took an active part in the fighting. Few people were not present with their army in battle, as in the case of Hideyoshi, when he sent his troops to invade Korea.

Zen

Buddhism was brought to Japan from China during the sixth century and from that time onward spread throughout the archipelago. During the time of the samurai there were several variants or sects of this same philosophy, although most warriors opted for Zen-type Buddhism.

Zen teaches its followers to seek enlightenment and salvation through meditation, which is achieved with great discipline. Since the ultimate goal of this philosophy is to seek spiritual harmony, which leads to a "flow between life and death," many warriors felt identified with and attracted to it.

Seppuku

One aspect to which much importance was attached was the yearning to die for one's lord or his cause. This was summed up in the practice of seppuku, a ritual suicide that was viewed in Japanese society at the time with great respect and admiration.

A clear example is the case of the famous samurai Torii Mototada, who, despite finding himself in adverse conditions facing a vastly superior enemy, managed to buy enough time for his lord Tokugawa Ieyasu to flee and was able to raise an army of great proportions and finally win at the Battle of Sekigahara.

After resisting the siege of Fushimi Castle for fourteen days, he committed seppuku to avoid the shame of defeat. The practice of seppuku was also widespread in the case of seeking to atone for some wrong committed, as a mode of protest or as a way of following one's lord to death.

Benefactors of the art

One aspect of the samurai that is almost unknown today is the contributions to the arts made by some daimyō during Japan's history. Many of these families had excellent training in literature and aesthetics as well as mastered war tactics.

Some characters that stand out for their contributions to art are Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who began the unification of the country during the Azuchi-Momoyama period through bloody wars.

Samurai often listened to and took part in the performance of musical activities as part of their daily practices to enrich their lives and knowledge.

Hideyoshi was the character by whom the tea ceremony became an art. The great irony is that the vessels for this ceremony were brought from Korea, a country that Hideyoshi invaded twice.

Hideyoshi hired two brothers who, under the supervision of the famous tea master Sen no Rikyū, created the raku style of vessels. Another daimyō who took advantage of Korean potters was the Shimazu clan of Satsuma, which made the region famous. Another example is Oda Nobunaga's contributions to the nō (能), to which he frequently resorted.

Gastronomy

Rice has been the staple food of Japanese society since ancient times. This also extended to the samurai, especially after the mid-15th century, when rice became part of their regular diet. Rice was cooked in various ways, either in a pan mixed with yasai (vegetables) and nori (seaweed), steamed alone or in the form of onigiri (rice balls).

Mochi (rice cakes) were also often prepared with rice flour or a mixture of rice and wheat flour. For a long time it was a problem to cook rice in the midst of campaigns, but Tokugawa Ieyasu devised a method for this: he provided iron helmets to his infantrymen and inside them rice was cooked.

In addition to rice there was tempura, a dish derived from Portuguese cuisine and whose name derives from "temporal" or "time, " and sashimi as we know it today. During the farewell banquets the warriors shared kachi-guri (dried chestnuts), konbu (seaweed) and sake.

These foods were arranged in three bowls symbolizing heaven, man and earth. This ritual differed considerably from that performed by sea pirates, who used to eat octopus because they can defend themselves in eight directions at the same time.

Women warriors

During the first centuries of Japan's history, the strong matriarchal charge of the society was evident. An example of this is the role and emphasis given to Amaterasu within the creation myth among all the kami. Among early Japanese chronicles, it is recurrent to hear of queens leading the army against enemy fortifications along the Yamato or the Korean Strait.

This was also recorded in Chinese documents, where an envoy claimed that a woman, Himiko no Yamatai, was considered the highest ruling authority in the country. From the Heian period onward, women ceased to participate directly and actively in the battlefields.

However, they continued to practice martial arts and self-defense techniques. The naginata was their weapon of choice because of its long reach and versatility, along with the yari. These weapons were often hung on the doors of military homes in case an intruder showed up.

Another weapon they specialized in wielding was a short dagger called a kaiken, which was useful in close-range combat. The kaiken also served as the weapon in which women committed the ritual suicide known as jigai. The latter differed from the male seppuku in that, instead of cutting the belly, the cut was made in the throat.

Among the most famous female warriors, Tomoe Gozen stands out. Of her it is said that, after killing several enemies in a single combat, the leader of the enemy forces, Uchida Iyeyoshi, attempted to capture her himself.

During the skirmish, Uchida tried to pull her by one sleeve to get her off her horse. This so enraged Tomoe that she turned on her adversary and cut off his head, a trophy she later presented to her husband. It is said that, in another battle, after several hours of combat, she was one of the last seven warriors standing.

According to legend, her last action was when, upon learning that her husband Minamoto no Yoshinaka was about to be defeated, she decided to enter the battlefield in order to give him enough time to die honorably by committing seppuku.

In an effort to achieve her goal, she rode to the most skilled of the enemy warriors and challenged him, trying to attract the attention of the rest of the combatants.

It is said that she effectively managed to defeat and decapitate her rival, however, when she arrived at the place where her husband was, he had died from the impact of an arrow. This discouraged her so much that she let her guard down and died at the hands of several warriors in the same place.

Western Samurai

It appears that the navigator and explorer William Adams (September 24, 1564 - May 16, 1620) was the first Englishman to arrive in Japan, as well as the first foreigner to receive the title of samurai.

William Adams, known in Japanese as Anjin-sama (anjin, "pilot"; sama, superlative honorific title of san) and Miura Anjin (三浦按針 the pilot of Miura) was an English navigator who, after being shipwrecked in the ocean on the Dutch ship Liefde, arrived on Japanese shores in 1600.

Shortly thereafter he met directly with Tokugawa Ieyasu and was interrogated for several weeks. Because Adams spoke some Portuguese, Ieyasu was able to communicate with him through his interpreters, who at the time were in frequent contact with Spanish and Portuguese merchants.

William told him about the "Protestant Reformation" and the ensuing wars in Europe between Protestant and Catholic countries, among other news to him.

Adams made such a good impression on the shōgun (despite the intrigues of the Jesuit missionaries, who said that the English were the "bandits and robbers of all nations, " so they called for all crewmen to be crucified as "enemies of Japan"),

that Ieyasu allowed the crewmen of the Liefde to return home, however he kept him as a personal advisor in matters of international trade, in addition to appointing him samurai and hatamoto and providing him with a fief valued at 250 koku with 80 farmers.

It was finally William Adams who would build the first western-type ships in Japan. These ships would make voyages as far as Mexico, Manila, and Spain. Williams died on May 16, 1620 in Hirado and never returned to his native country.

The story of William Adams is told in the novel Shogun: Lord of Samurai by writer James Clavell, from which a miniseries was filmed in 1980, starring American actor Richard Chamberlain as the English pilot John Blackthorne and Japanese actor Toshirō Mifune, playing the role of Lord Toranaga.

Samurai in popular culture

Movies

Ever since cinema became popular, a recurring theme in Japan was that of the samurai. While in its early days the theme was approached in a more dramatic way, after World War II they were transformed into action films with darker and more violent characters, where directors focused on presenting psychologically or physically scarred warriors.166 Akira Kurosawa, one of the most famous Japanese directors, stylized and exaggerated death and violence in "samurai epics" films. The samurai he depicted in his works were solitary figures, more concerned with concealing their skills than flaunting them.166

In Japan, the term chanbara (チャンバラ) is used for this genre of film.167 This kind of film is regularly set during the Edo period. chanbara is also a subgenre of jidaigeki or "period drama, "167 which involves setting a film in a historical period, not necessarily in a samurai or sword-fighting setting.

Nowadays, the samurai theme has become globalized and one of the greatest exponents of this type of films are those of Akira Kurosawa himself, which have been internationally recognized. One of his great films, The Seven Samurai, has undergone several adaptations, among which the film The Magnificent Seven and a "Western" by John Sturges in 1960 stand out.

Another of Kurosawa's films, The Hidden Fortress, served as inspiration for part of the plot of George Lucas's Star Wars as well as the characters of Obi-Wan Kenobi, Master Yoda, C-3PO and R2-D2.168

Another example is provided by the film The Last Samurai, starring Tom Cruise, which is inspired by both Saigō Takamori's Satsuma Rebellion and the story of Jules Brunet, a French captain who fought alongside Enomoto Takeaki during the Boshin War.

- The Last Samurai, a 2003 film directed by Edward Zwick.

Finally, 2013 saw the release of the film 47 Ronin, which alludes (albeit with fantasy parts) to the legend of the 47 rōnin.

Manga and Anime

Samurai stories have been dealt with profusely in the comic book of their country, called manga.

There, after World War II, propaganda was replaced by entertainment (Akado Suzunosuke by Eiichi Fukui, 1954; Tenpei Tenma by Taku Horie, 1957), although the great masters of this type of story were Sanpei Shirato, author of Ninja Bugeicho (1959), Sasuke (1961) and Kamui (1964) and Kazuo Koike/Goseki Kojima, authors of The Lone Wolf and His Cub (1970).

In other traditions, there are also important works starring samurai, such as Ronin (1983) by the American Frank Miller or Kogaratsu (1985) by the Belgian Bosse/Michetz.

Throughout the history of manga and anime, numerous series have been created with samurai as protagonists, such as Rurouni Kenshin, Samurai Champloo, Afro Samurai, Samurai 7, Shiguiri, Yoroiden Samurai Troopers, Gintama, Sengoku Basara, Brave 10 and many others....

In Western animation, the American animated series Samurai Jack became very popular.

Outside of animation, elements of the samurai warrior were adapted in the tokusatsu live-action series Samurai Sentai Shinkenger and its American adaptation Power Rangers Samurai.

Video games

As in anime and manga, samurai have served as inspiration for the development of several video games and sagas such as Samurai Showdown, Warriors Orochi, Dinasty Warriors, Nioh, Four Honour, Total War: Shogun, Onimusha, Bushido Blade, Genji: Dawn of Samurai, etc.

In the video game Age of Empires II: The Age of Kings, the samurai is the unique unit of Japanese civilization.

In the video game Age of Empires III: The asian dynasties, the Japanese civilization appears with the majority of units and a Japanese campaign of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

In the video game Ghost of Tsushima (2020), the habits and designs of the bushido code of justice and honor are described. The title firmly recreates a setting based on the cinematography of samurai cinema and the films of director Akira Kurosawa to portray the Mongol invasion of the island of Tsushima.

The protagonist of the story, Jin Sakai, a samurai sponsored by a daimio of the Shimura clan, who is also his own uncle, confronts and questions this ethical code in order to defeat the invading enemies.

The conflict between uncle and nephew for using methods more typical of the shinobi than of the samurai, is the engine that encompasses the story of the videogame. It was well received by critics and the public and was praised by many media in Japan.